How did you get into making art?

When I was six or seven, my mother dedicated a wall in our dining room for me to fill with drawings. It was my first studio. I had great teachers in public school, and then in art classes at Barnard College and Columbia University I found colleagues and mentors that showed me how to be an artist. Five years after undergrad, I pursued an MFA at The School of Visual Arts in NYC, where I was able to really develop my own language for painting.

What are you currently working on?

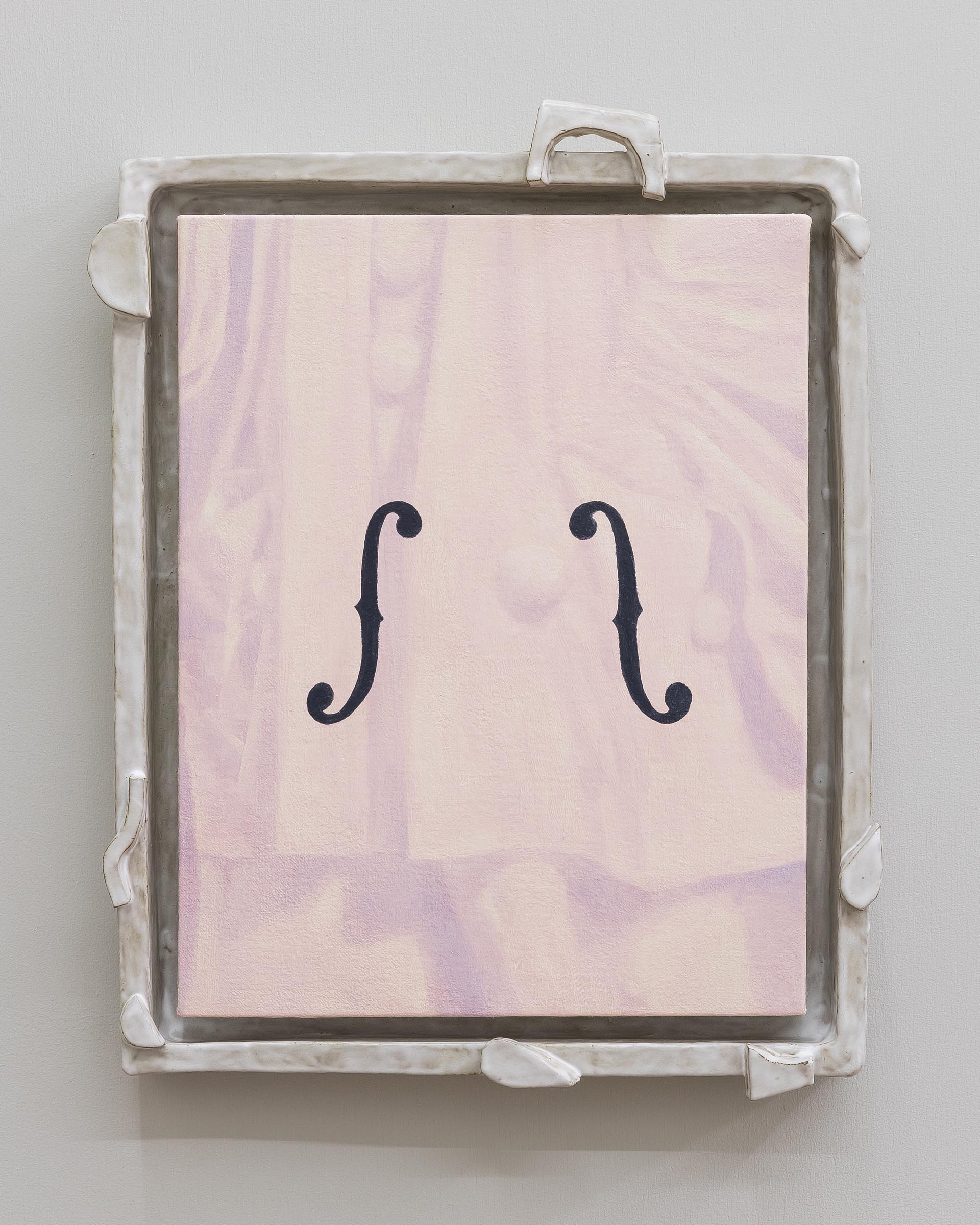

I am making oil paintings, set in ceramic or mixed-media frames. They investigate how images and stories are shared and translated across generations. The idea of performance has become primary in my recent work. I am drawn to the theater because it is a space parallel to that of a painting, where action can be manipulated outside the rational constraints of our physical world.

My current subjects are wide-ranging historical entertainers: Pierrot and Harlequin, Sappho (the ancient Greek poet), the magician’s assistant, the mime. My themes are universal, but my connection to them is personal. I resonate with being a performer in the different roles I have played so far in my life: an artist, a mother and wife, a person at an institutional day job, a writer, a professor.

My paintings investigate how images and stories are shared and translated across generations.

Emily Weiner

What inspired you to get started on this body of work?

I realized at some point, soon after graduate school, that the symbols and geometries in my paintings would recycle from one work to the other—often inadvertently and over a long period between paintings. They seemed to reveal the longevity and authority of a single geometry across time and place, not just in my studio but throughout a larger collective image bank. (Is it a coincidence, for example, that a triangle implies power in the form of an Egyptian pyramid, in the all-seeing eye on the American dollar bill, in the sacred geometry of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, and in the Enneagram?)

A range of familiar characters and forms—borrowed from Art History, Jungian archetypes, playing cards, and theater—wound up in my compositions. I have been continually inspired by this emergence of common themes from within a seemingly random set of cultural references.

Do you work on distinct projects or do you take a broader approach to your practice?

I take a broader approach. I can’t pre-plan a series, it comes together as the paintings take shape. I approach each canvas without a clear plan, and by working in many layers of paint, I find synchronicity in combinations of colors and forms. These combinations form their own narratives, which wind up having strong resonances with both personal and collective experience. I build multimedia frames for each painting through a similar intuitive process. By paying attention to the frame of the work, I hope to highlight some important aspects of painting that may have been neglected in history—especially the role of ornamentation, craft, ceramics and other motifs historically designated “women’s work.”

What’s a typical day like in your studio?

I drink coffee, clean up the mess from last painting session, and start painting. Sometimes I work on a single painting in a day, or I work on several of my canvases in progress. My dog Marcel walks in and out to check in. I stop for lunch and then get back into the studio, turn on music or an audio book. I set a timer to remind myself to put down the brush and leave to get my son from day care.

Who are your favorite artists?

Both conceptually and stylistically, my work takes inspiration from so many artists. My forever favorites are Georgia O’Keeffe and Gerhard Richter—opposites in their emotional approaches to painting. I am fascinated by the Swedish artist Hilma Af Klint, for whom the spiritual was central, and who was making abstract imagery in the early 1900s—before Kandinsky, Mondrian, and Malevich—though she worked in obscurity from the art world. Forrest Bess and Charles Birchfield have also been influential to my work; I admire their connection to the unconscious, and the dream languages that pervade their paintings. Agnes Pelton is an artist that I encountered first a decade ago, and I was amazed by the kinship I felt between my paintings and hers, in terms of color and framing but also in her way of channeling a transcendent quality. I have also been looking at work a lot recently by Natalia Goncharova, the avant-garde Russian painter and set designer, especially her theater paintings and her depictions, as an outsider, of Jewish life in Tsarist Russia. The rock art in Chauvet cave, made 33,000 years ago, is something I think about often, and is astonishing in its immediacy and lucidity, and a reminder of our primordial connection to this world and each other.

Where do you go to discover new artists?

In the past I would go to galleries and museums. In New York, I made a living as an art writer, among other jobs, so I saw art constantly for two decades. Moving to Nashville in 2018, I discovered so many brilliant artists through friend introductions, collaborations, and studio visits. Now Instagram is the main way that I keep up with what is going on—in Shanghai, Norway, New York—even a few minutes away in Nashville.

Learn more about the artist by visiting the following links: