How did you get into making art?

I come from a middle-class family with no relationship to art or interest in art making so it was a pretty lonely path. I knew early that I wanted to be a sculptor.

I drew a lot everywhere and on everything but I soon became interested in object making more than anything else. I have memories I revisit often of dismembering and stealing parts of a friend’s toys to later (secretly) assemble them with mine.

I also had an obsession with erasers. I had a big collection of them in all different colors, shapes and consistencies. Most of them were stolen, used and manipulated until they turned to tiny bits and pieces so small and rounded they looked like glass marbles.

My favorites were the old-fashioned “Pelikan” ink erasers, made with sand and so abrasive that they would always dig a hole in any surface. – as the ink was finally gone so was the paper. I also had an interest in ancient erasers made out of bread. I still have a fascination with the palimpsest and erasure as ideas that instigate or trigger a certain type of art-making.

What are you currently working on?

I’m currently finishing a new series of sculptures using iridescent glass and chainmail.

The idea was to depict biomorphic forms that slowly merged with vultures of body parts which metamorphose reveals as hybrid objects or ghostly creatures.

I started by thinking about these sculptures as wearable or portable elements that could function as bodily support structures or defense mechanisms. Most of their forms take on abstract qualities, that I repeated and distorted across biomorphic armatures that somehow meet prêt-a-porter.

By encasing water inside the blown glass works and combining it with ancient chainmail techniques, these sculptures open up to an experience of the body increasingly intertwined with and mediated by the social and political. Using the process of slumping glass over molds and combining it with armoring produced using traditional chainmail weaving techniques, I am interested in exploring how these politicized materials form our understanding of the social constructs of archeology, history, and gender.

I still have a fascination with the palimpsest and erasure as ideas that instigate or trigger a certain type of art-making.

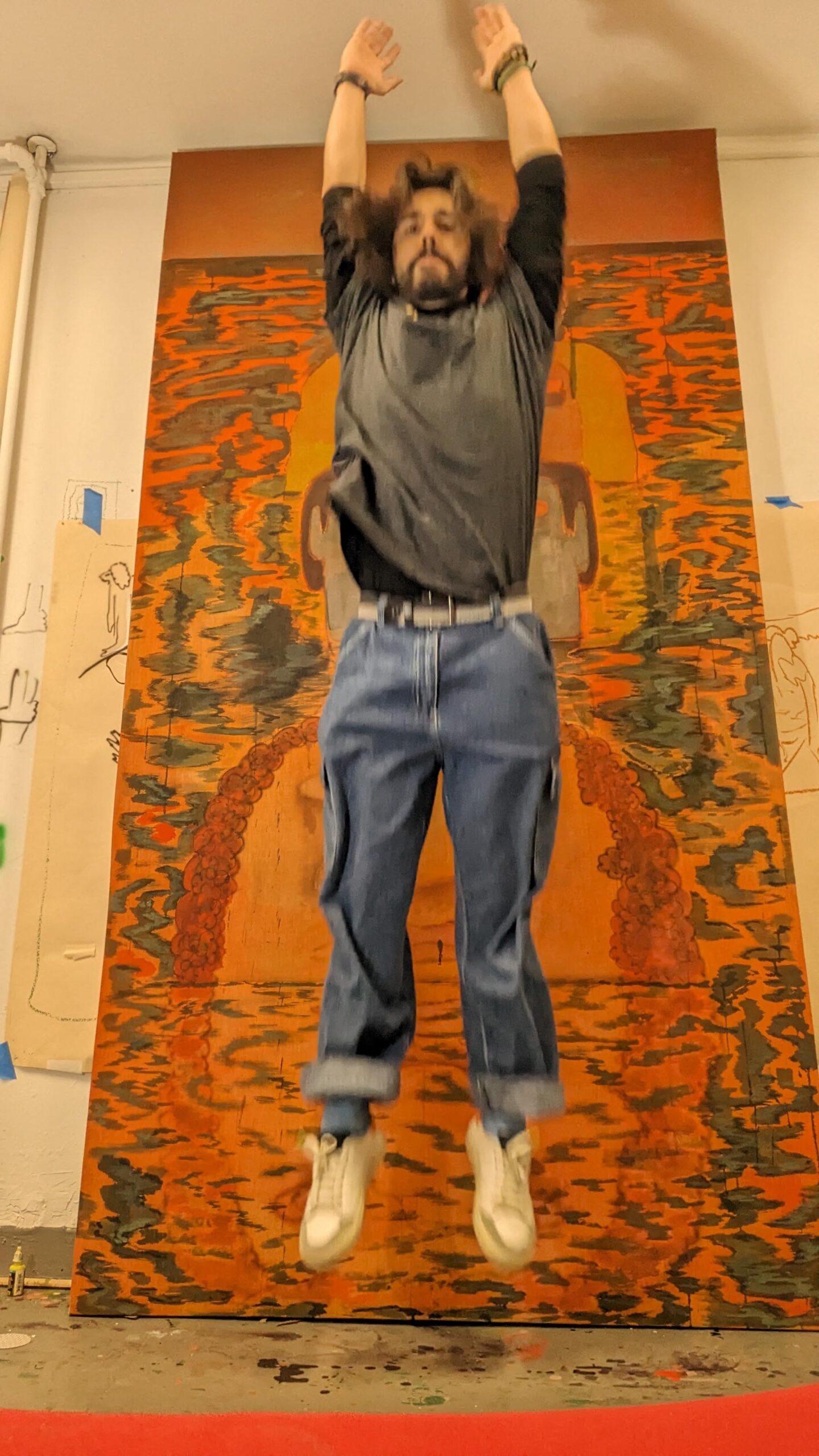

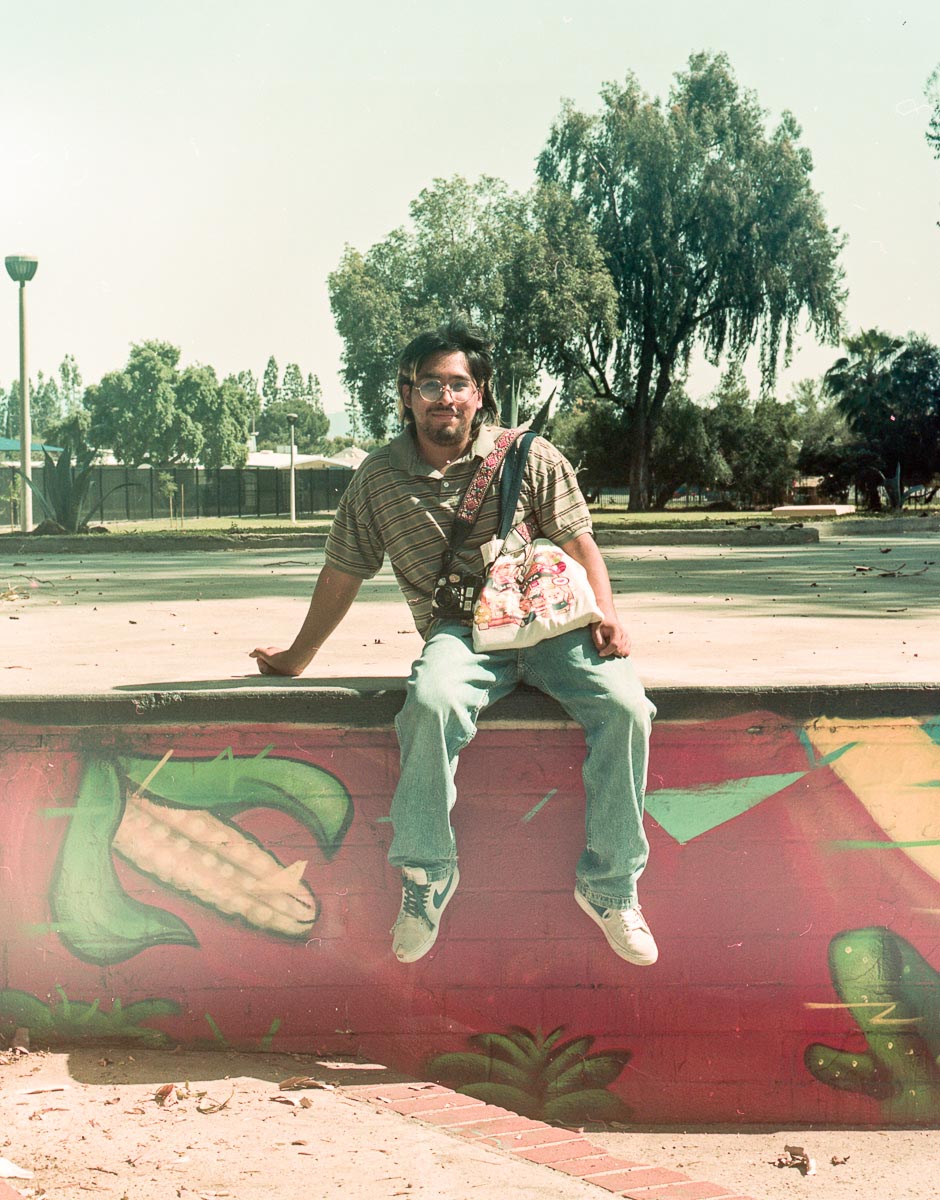

Andreia Santana

What inspired you to get started on this body of work?

I started to include glass work in my metal sculpture practice in 2020, during the pandemic. While spending time isolated in my apartment, I was thinking a lot about the materiality of my work and how it would be affected by the social consequences of what we were experiencing globally.

The idea of blowing glass at a time when social distancing and masks were encouraged was intriguing for me as the glass vessels kept the breath and saliva of the blower. I remember when some museums started to make their collections available for online viewing through data bases or virtual tours while its physical space was totally empty. This allowed me to be familiarized myself with Torino’s Egyptian Museum collection.

At the time I was interested in investigating the composition of archives, the material conditions that allow something to be archived, the compulsions and desires that evoke the appearance and disappearance of objects, the cultures and micro-cultures of circulation, manipulation and administration that allow an object to contribute to the resistance of specific social formations.

I focused on their collection of Soul Houses (Casa Dell’Anima)—a strong part of early Egyptian funerary practices usually placed on the surfaces of graves with the intention of providing accommodation and sustenance for the deceased in the afterlife. These fired clay models could take many forms from basic offerings-trays to replica houses or cult chapels.

I wanted to perceive these Soul Houses as well as other artifacts partially destroyed or damaged by pests, bacteria, fungi, or any other natural disaster suffice as shelters for new inhabitants and become animated with a spiritual essence through the occupation of these species, placing themselves as constantly changing and incessantly contemporary forces.

Do you work on distinct projects or do you take a broader approach to your practice?

It really depends. I would like to think that my practice includes both. I produce work for distinct projects and take a broader approach sometimes even at the same time. For instance, when I am invited to participate in specific projects I tend to culminate and merge what I’m creating in my daily studio practice with something that is a personal artistic reaction to a proposal/site/exhibition space etc. This overlapping of methodologies became a very positive strategy for me, providing less pressure on “finishing” a body of work and allowing it to be contaminated by exterior energies.

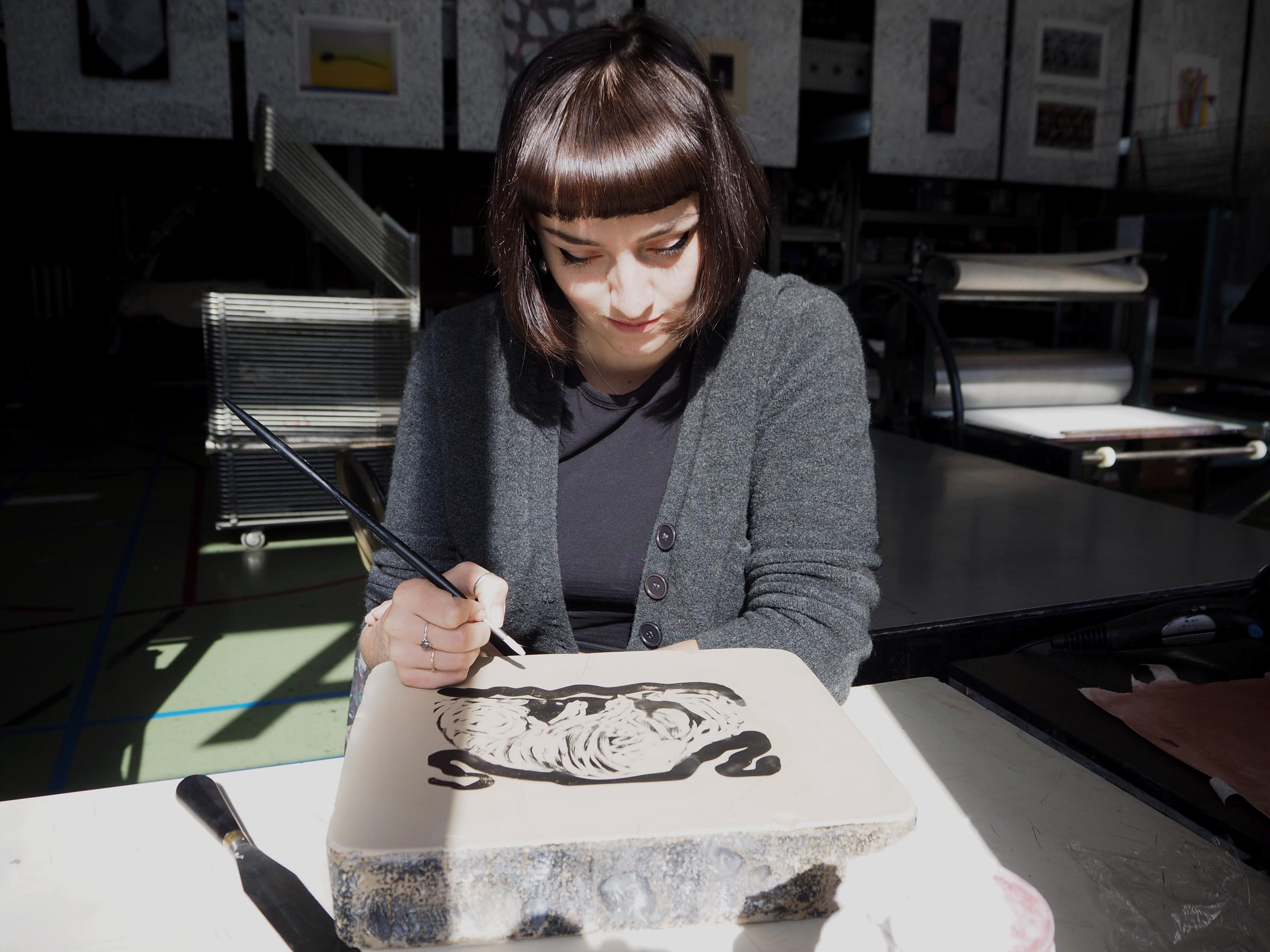

What’s a typical day like in your studio?

I like to think about the studio as something that is not confined to a specific space. I tend to travel a lot for exhibitions, research, or even residencies so I was always forced to adapt myself to keep producing work while in different places and environments. It’s challenging but sometimes extremely liberating.

I remember a quote I deeply relate to and carry in my head often: “We’ll start precisely from where it all began: the artist’s studio, a precarious, itinerant, temporary home studio in which art is the only reason for being.” I found these words by Francesco Urbano Ragazzi in the book about the work of Chiara Fumai “Poems I Will Never Release”.

My studio practice is made of intense “waves” production-wise but I can say that usually there’s a previous research part that takes place outside the studio space and that conceptually and visually informs what is developed later. This pre-production stage is left to merge with external impulses and daily lives that surround me, becoming part of my subconscious and leading me to sometimes dream about my sculptures before making them.

At the moment, my practice has acquired a more physical and intimate dimension, using organic materials (such as fish glue smuggled across the ocean in my personal luggage) and sculpture techniques ( a mix of traditional and experimental processes are used to alter, slump, swell and sag the glass as it submits to its metal opponent, such as mold making, glass slumping, and printing) combined with the transformation of found objects, collected on daily walks.

Who are your favorite artists?

Currently I am looking a lot to the work of Carol Rama, Curtis Cuffie, Chiara Fumai, and John Giorno to name a few.

Where do you go to discover new artists?

Usually I go to as many exhibitions as possible – especially artist-run spaces or non-profits so I’m informed on new artist’s work and practice outside the mainstream art settings. If I’m curious about someone’s work I often ask if I can come for a studio visit. I prefer in person interactions with artists but social media also helps finding emergent artists or with less visibility.

Learn more about the artist by visiting the following links: