How did you get into making art?

I was obsessed with cartoons and comic books when I was a child. The infinite possibilities of creating entire worlds with simple lines and limited colors captivated me. I spent hours and hours drawing my favorite characters and making flip-book animations with stick figures.

In college, I was introduced to sculpture and installation. The three-dimensionality with tactile materials opened up a new world for me. I loved the fact that as beings stuck in three dimensions, our perception of space and objects is not whole but rather fragmented and reduced to two-dimensional images projected onto the retina. That limitation requires us to move around the object or space in time to see all sides. I loved that I was working with something I could never fully understand.

I found a particular fascination with found objects and the rich connections they offer to the world around us. Each found object carries its own unique story waiting to be discovered and explored.

Since then, sculpture and installation have remained my primary mediums, allowing me to continue exploring the interplay between materials, space, and narrative.

What are you currently working on?

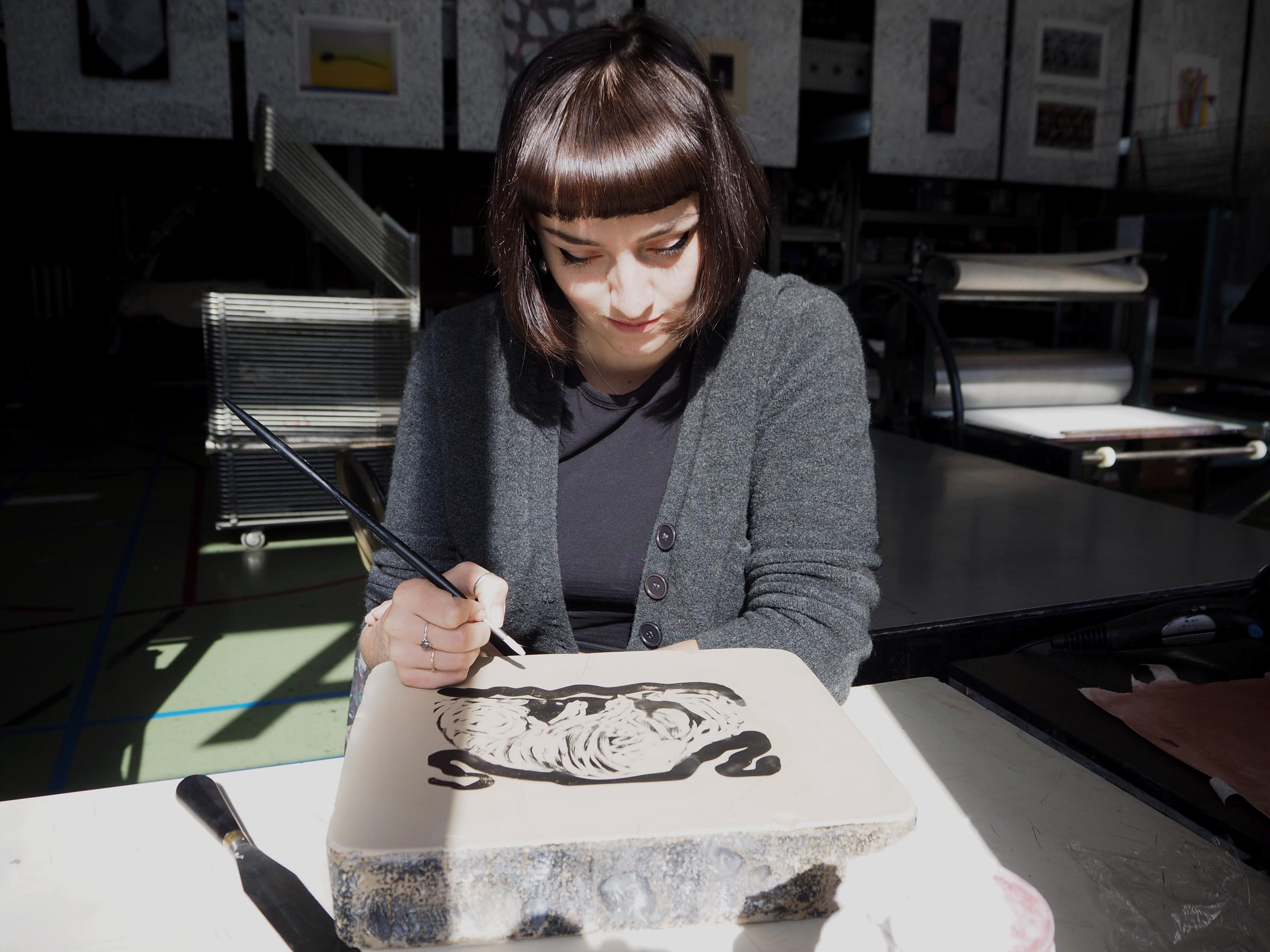

I am currently working on two projects centered around the theme of labor. One a series of mask sculptures that I began in 2021. These sculptures draw inspiration from characters in traditional Korean mask plays, which were created and altered by numerous people over centuries. The beauty of this tradition is in its collective nature rather than individual creativity. My contribution to this tradition does not stem from creating new designs but from materials I use – wood scraps and sawdust collected from my work as a professional woodworker. These remnants, bearing the physical traces of my labor, come together to form intricate patterns, symbolizing the communal essence of labor and community. Additionally, I incorporate incense made from hardwood sawdust, a material typically seen as a health hazard for woodworkers but repurposed here for viewers to inhale and find solace.

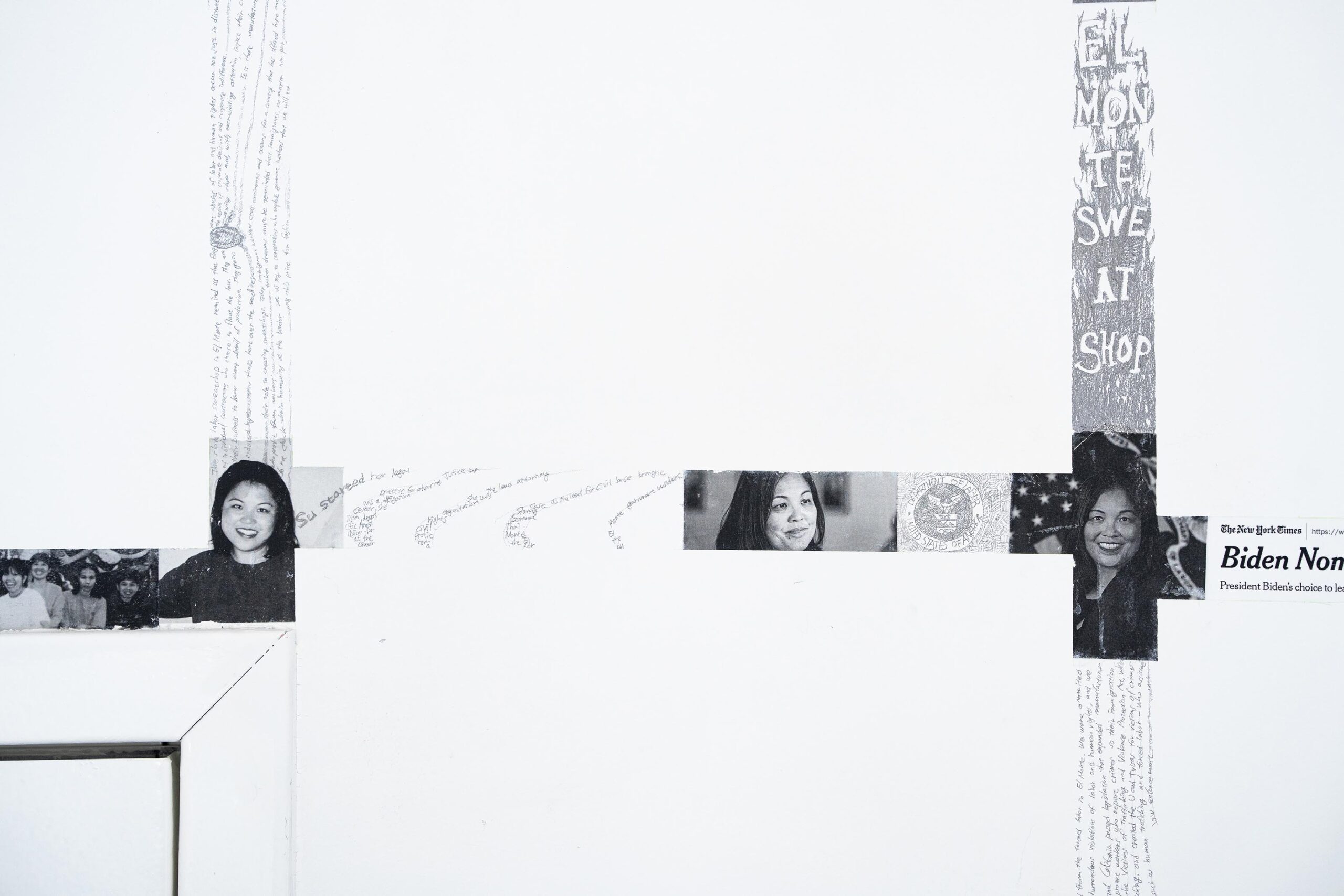

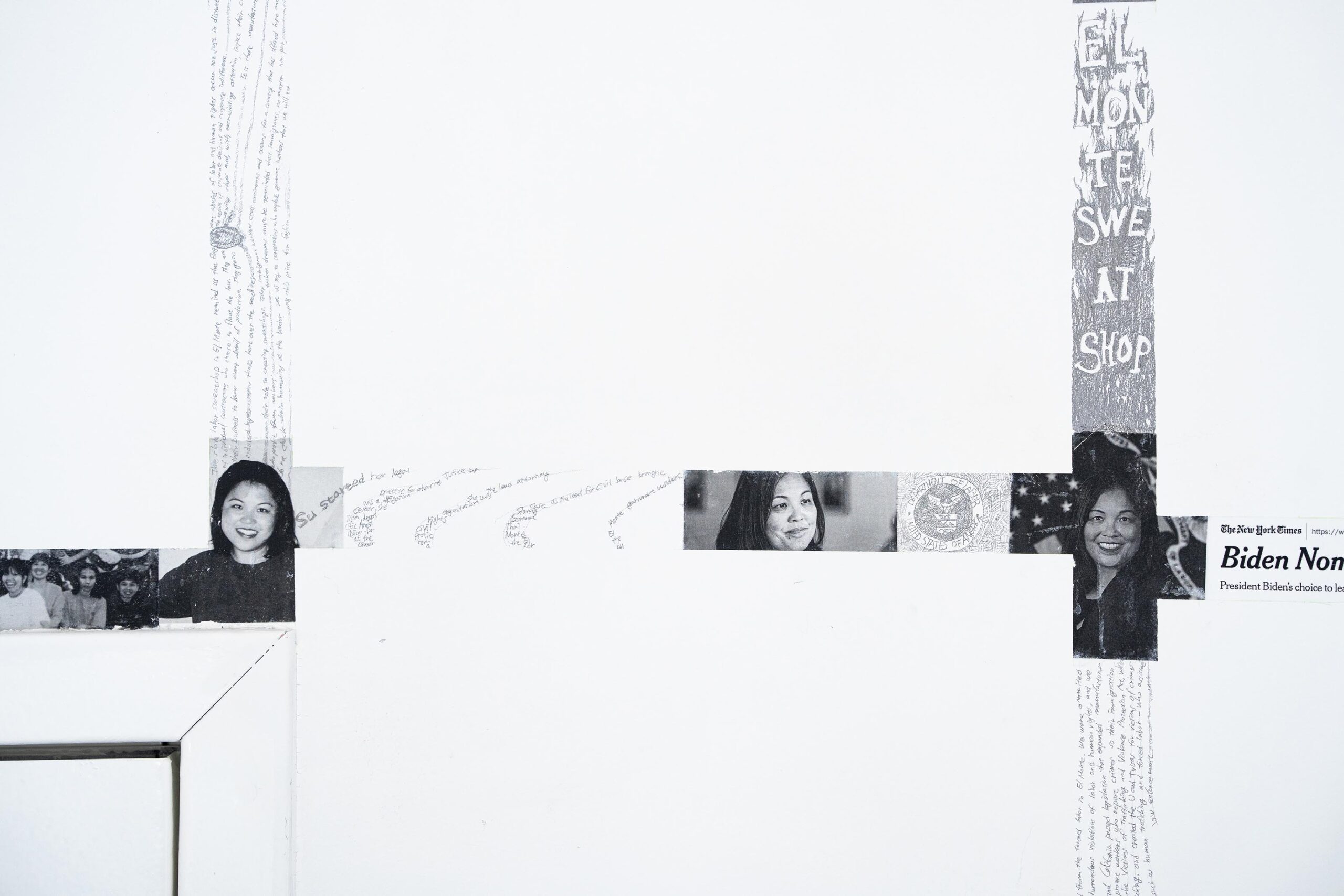

The other is a series of fabric sculptures titled Before the Last Spike. They are made of fabric scraps collected from garment factories in LA and NYC, where the majority of the workers are recent immigrants. I sew them together keeping the original shapes, which are also negative space of what we wear every day and evidence of everyday factory labor. They are rust-dyed using railway spikes, symbolizing the labor of Chinese immigrant workers who constituted a significant portion (80%-90%) of railway labor. The marks left by the spikes serve as a visual testament to the often invisible and unacknowledged labor that has long sustained American industries.

I have come to realize that my practice has become a journey of imagining a world beyond the confines of the capitalist systems I’ve grown up in.

Jinseok Choi

What inspired you to get started on this body of work?

My experience as a woodworker, studio assistant, and art handler, influenced my perception of labor and blurred the distinction between artistic labor and physical labor. This experience also prompted a reevaluation of notions surrounding authorship and copyrights. Delving into the history of the American garment industry, where immigrants have historically constituted the primary workforce, I became acutely aware of the systemic marginalization of those who have played pivotal roles in its development. The stark disparity between the visibility afforded to fashion designers and brands, contrasted with the invisibility of immigrant laborers who produce the garments we wear daily, is undeniable.

I have come to realize that my practice has become a journey of imagining a world beyond the confines of the capitalist systems I’ve grown up in. Along this path, I continually encounter traditional thoughts and values within myself that I’m working to unlearn.

Do you work on distinct projects or do you take a broader approach to your practice?

Both. I used to believe my projects were distinctly different from one another, both in form and content with few connections among them. However, I’ve come to realize that each project has always been shaped by my direct and indirect experiences, the broader socio-political contexts surrounding them, and my stance towards them. While I may work on different bodies of work, I now understand that they all originate from my attempt to grapple with the multiplicity and complexity of the world—a task inherently bound to fall short, much like our inability to see all sides of a three-dimensional object simultaneously. So each project is a fragment of a broader approach to my practice.

What’s a typical day like in your studio?

It varies greatly depending on the stage I am at in the process of a project. It could look like office work just reading, writing, and staring at screens, but also it could be constant production with various materials and tools. Sometimes I go outside for field research and interactions with people. I am still trying to figure out the right balance among those.

Who are your favorite artists?

My answer to this question is always different depending on when you ask me. Recently, I have been moved by the works of Every Ocean Hughes and my close friend, Eusung Lee.

Where do you go to discover new artists?

I try to check out as many exhibitions as possible, particularly those at artist-run spaces and experimental venues. Also, I look up the artists who have worked with those venues in the past. I find this approach helpful as it exposes me to artists who share similar interests with me but have taken entirely different paths in their practices.

And I stumble upon interesting artists on social media as well.

Learn more about the artist by visiting the following links: