How did you get into making art?

I grew up in Lima, Ohio, a small city located in the northwestern part of the state. A true embodiment of the term rust belt, it is a place with declining industries surrounded by flat farmland and is consistently uneventful. I credit the slowness of my hometown as the place where I learned how to be content observing and translating those observations into my creative practice now. I spent much of my childhood outside riding bikes, running in parks and cemeteries, and going to fishing derbies with my grandparents. Raised by my white mother who worked at a local fast food restaurant for 45 years and my black father who worked as a mechanic, I first experienced much of the world in a predominantly white catholic school as a mixed person often feeling out of place but assimilating nonetheless. Growing up in Ohio, I always had a love for insects and other microcosmic systems. Understanding how pests impact things like crops and trees, I always found an escape from my world by getting lost in their patterns and structures. I built my first bug catcher when I was 7 and my parents put me in art classes at our local art center (Art Space) at an early age. I was convinced I would become a zoologist like Jack Hannah whose tv show I faithfully watched each week and later when I left for college I decided I wanted to be a psychologist.

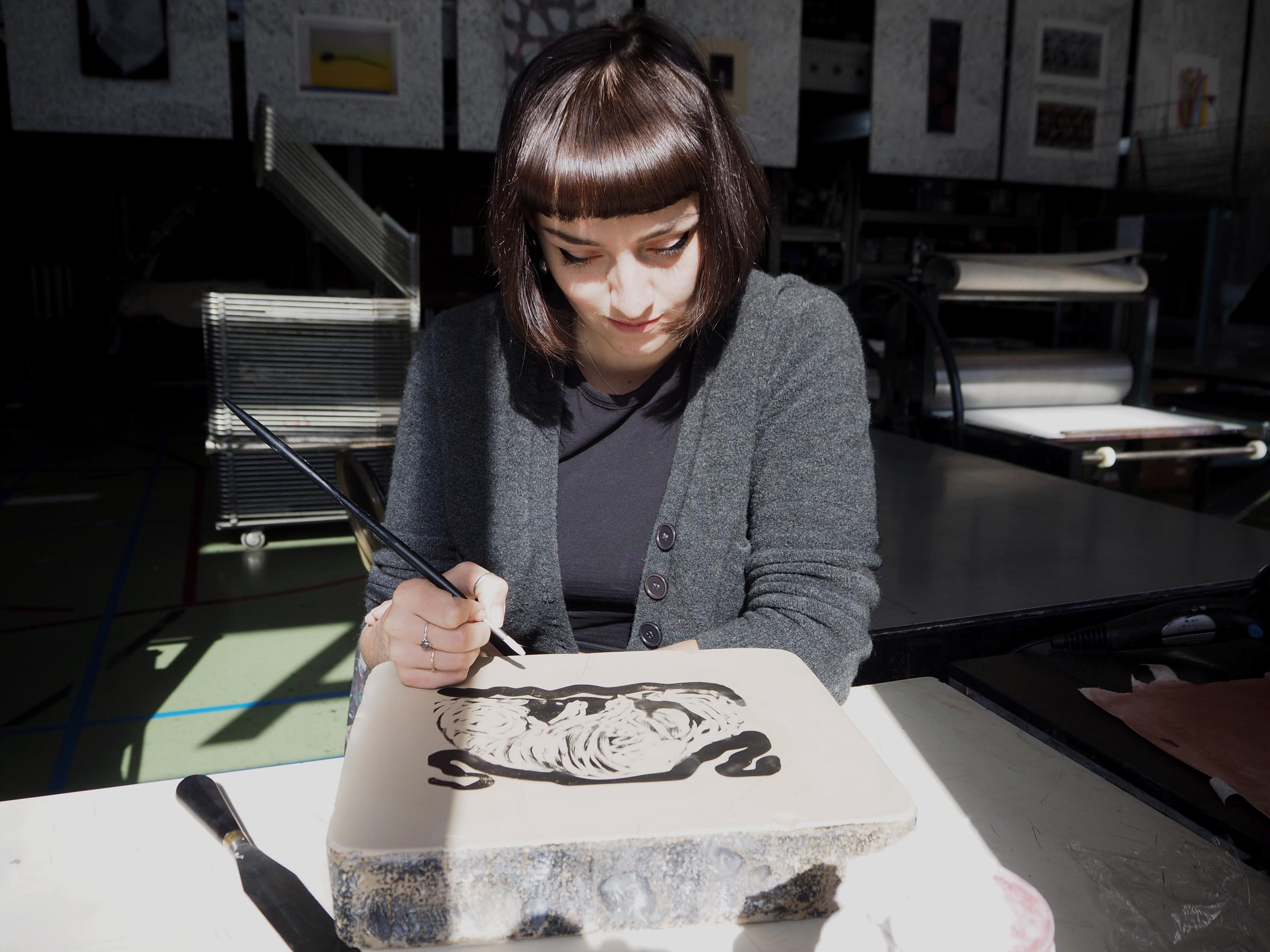

I studied at The Ohio State University where my life and creative practice was changed and shaped. Originally as a psychology major I took one of my first classes studying primate psychology. We made multiple visits to the primate research lab where chimpanzees were learning how to communicate on custom touch screen devices made by researchers (this was before iPads) to communicate their feelings and things like what they wanted to eat. After taking that class I knew that I wanted to find a creative way to engage with other species and learn how to make devices or other interfaces that made interspecies communication possible. I changed my major to Art and Technology where I studied under two pioneers in interactive bioart, Amy Youngs and Ken Rinaldo. My experience in the Art and Technology program allowed me the flexibility to explore the convergence of art, technology, and science while learning how to write code, create 3D models, animations, and learn techniques I had never had the chance to explore in the sculpture shop. It was a true hub of hybridity where the silos of art making were broken down instead of upheld. This is where my art practice truly began and I return to things I learned there in my practice now, studying there truly changed my life.

Currently my work explores human, animal, and environmental relationships through sculptures and installations created using computational processes. My work uses the transformation of data and material through digital fabrication processes such as 3D scanning, 3D printing, laser cutting, and CNC milling to create installations and sculptural objects. Translating data gathered from the environment, my work travels through various levels of software mediation while frequently originating through technologies that we carrying our pockets. Investigating the paradoxical bond between human-made urban landscapes and natural ecological systems, my work is an evolving series of objects and installations that question our contributions to our rapidly changing planet. Regularly examining other species and landscapes in relation to ourselves, I question humans’ analogous existence as the largest and most complex pest-network on the planet. My work is systematic both in construction and in concept, often a direct reflection of observed microcosms found at the surface of our feet, in the web of a digital mesh, and born out of the braided entanglements between ourselves and the other species of plants and animals with whom we share our world.

What are you currently working on?

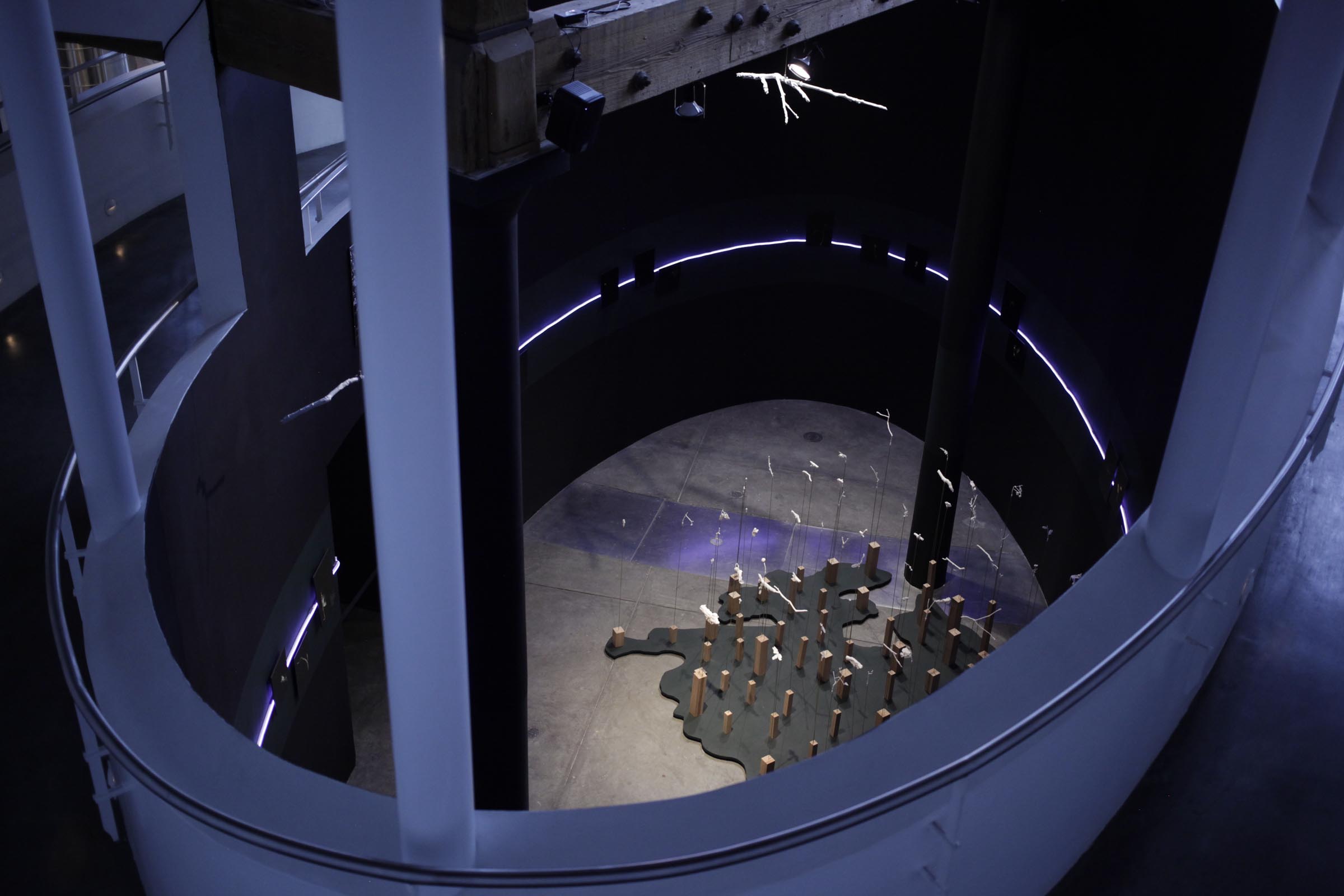

I just installed a solo exhibition (titled Suspended) at the Contemporary Art Center New Orleans where I was an artist in residence in the spring/summer of this year. I relocated to New Orleans, my wife’s hometown, in July 2020 when difficulties of the pandemic forced us to leave the LA area, though I traveled back and forth to continue my teaching appointment in Long Beach.

Despite being a long time continuous visitor to New Orleans, living there requires one to enter with a willingness to be open to learning and acknowledging the true histories of this nation. It is an incredibly special place, as a city and land whose people are incredibly kind and communal, and whose histories are intricately important to this countr. Simultaneously one cannot exist or visit New Orleans without acknowledging the history of slavery, displacement of natives, and the fragility of the land across centuries to the current. I have lived in 5 major cities and whenever I move one way that I learn about a city is by taking regular walks, especially around the city, in parks, and along bodies of water.

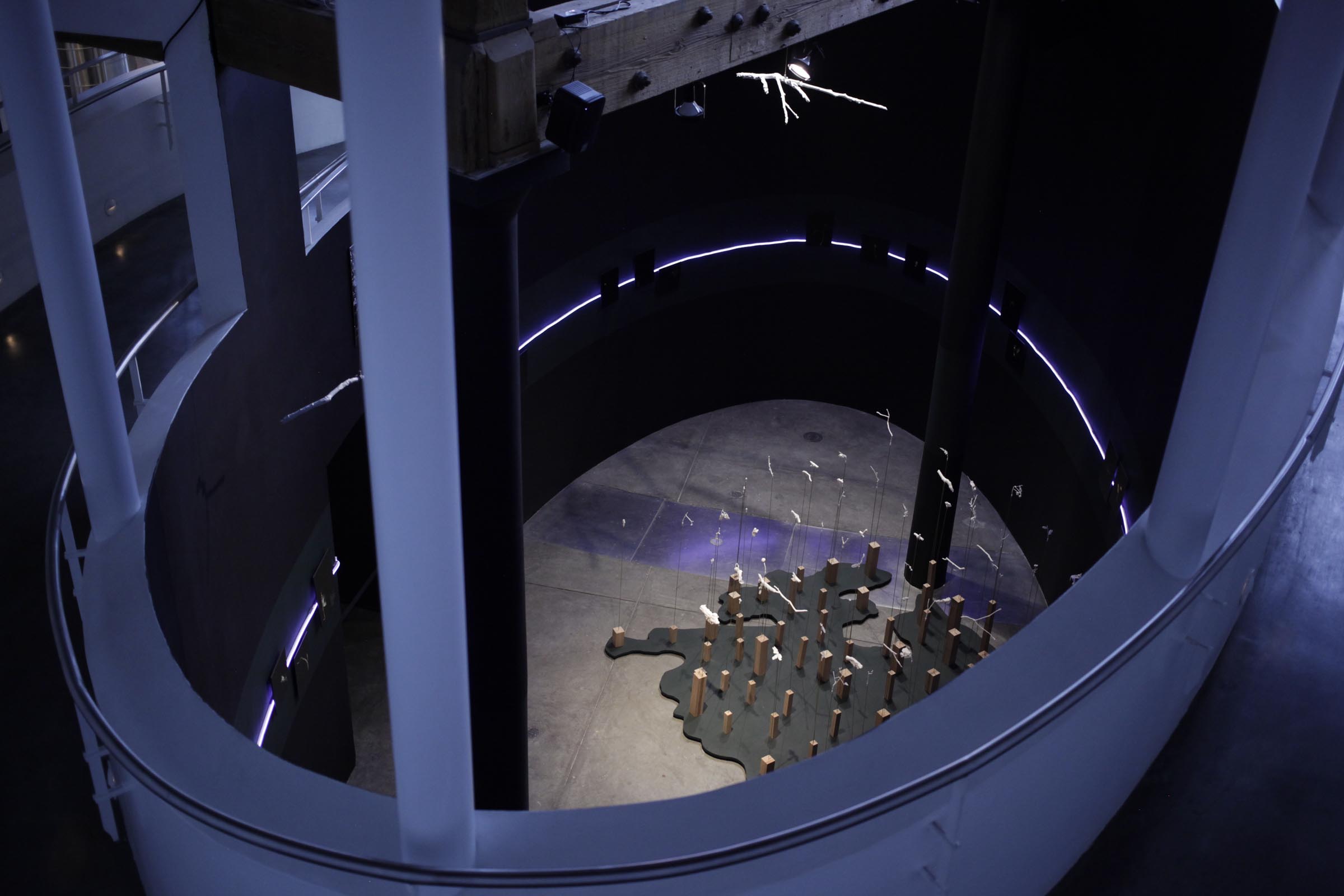

My most recent work in Suspended is an exploration of what is speculated to be the oldest live oak in the city of New Orleans. Located in City Park, the McDonogh Oak has existed for over 800 years with a trunk that spans over 25ft in diameter. It is easily identified by locals and visitors alike by the colonnade of telephone poles that surround the tree to prop up its limbs, a common mediation technique used to protect and extend the life of live oaks. Once part of the Jean Louis Allard Plantation established in the 1770’s, the location on which the tree sits was later purchased by John McDonogh who donated the land to the city upon his death in 1850. The tree was named in honor of this gift to the city and still retains McDonogh’s namesake despite its existence long before his proprietorship of the land and his complicated relationship with slaveholding. As society begins to acknowledge the truths of the past and unlink the names of those who perpetuated the dark realities of our nation’s history from monuments, street names, and historic sites, the tree and its name still persist.

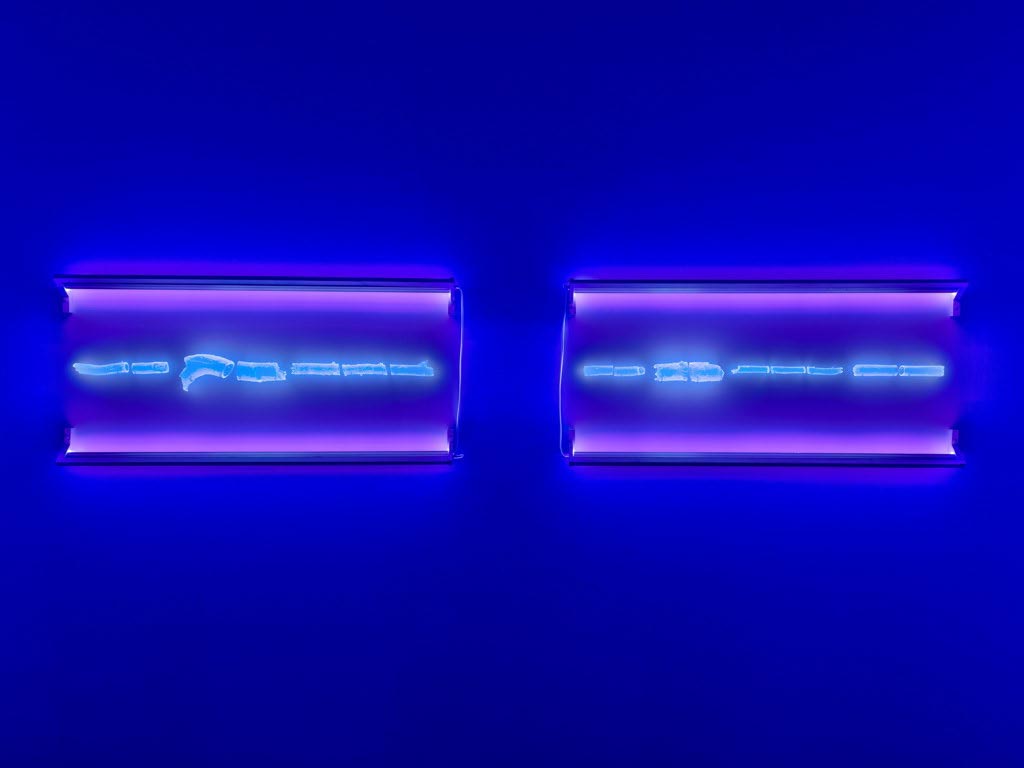

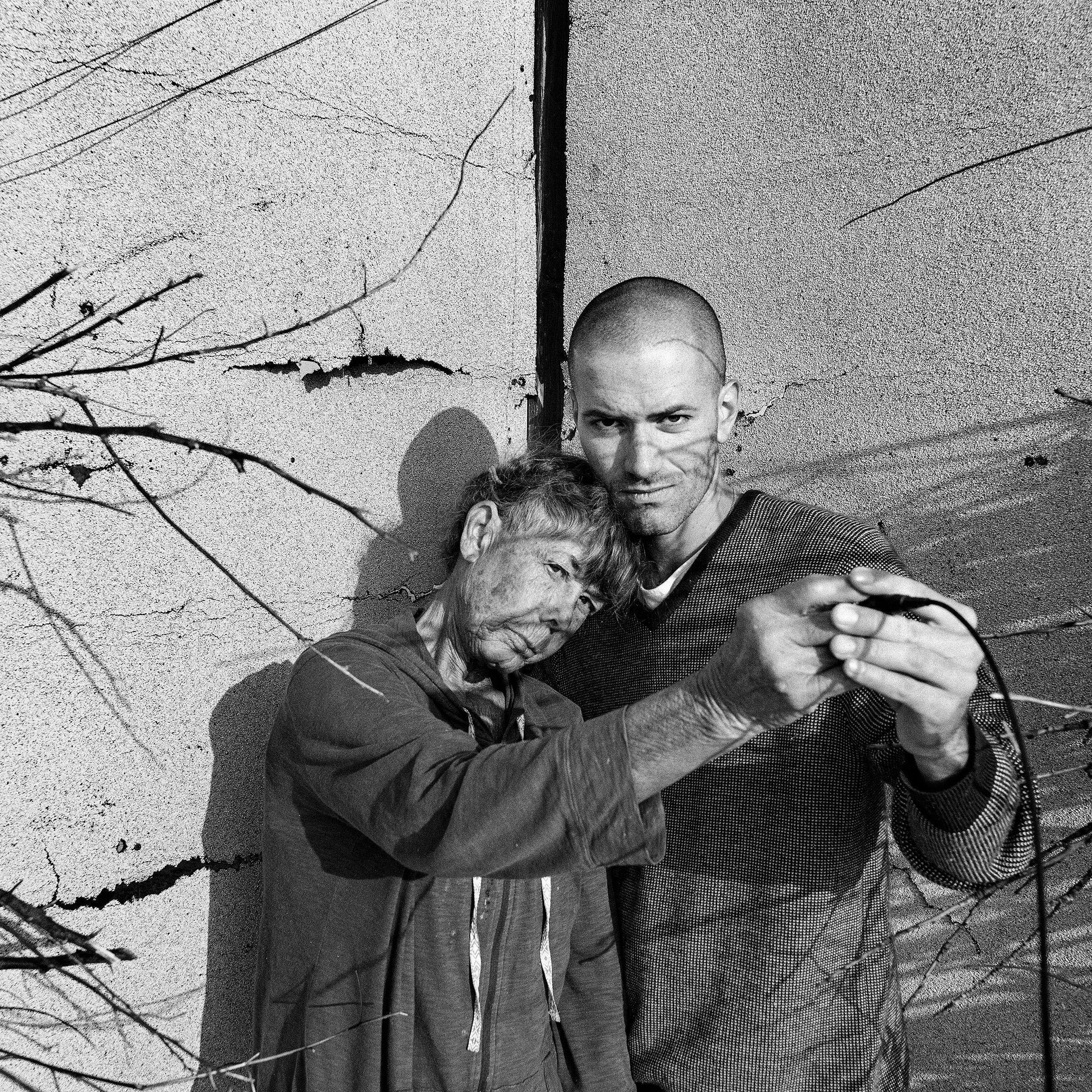

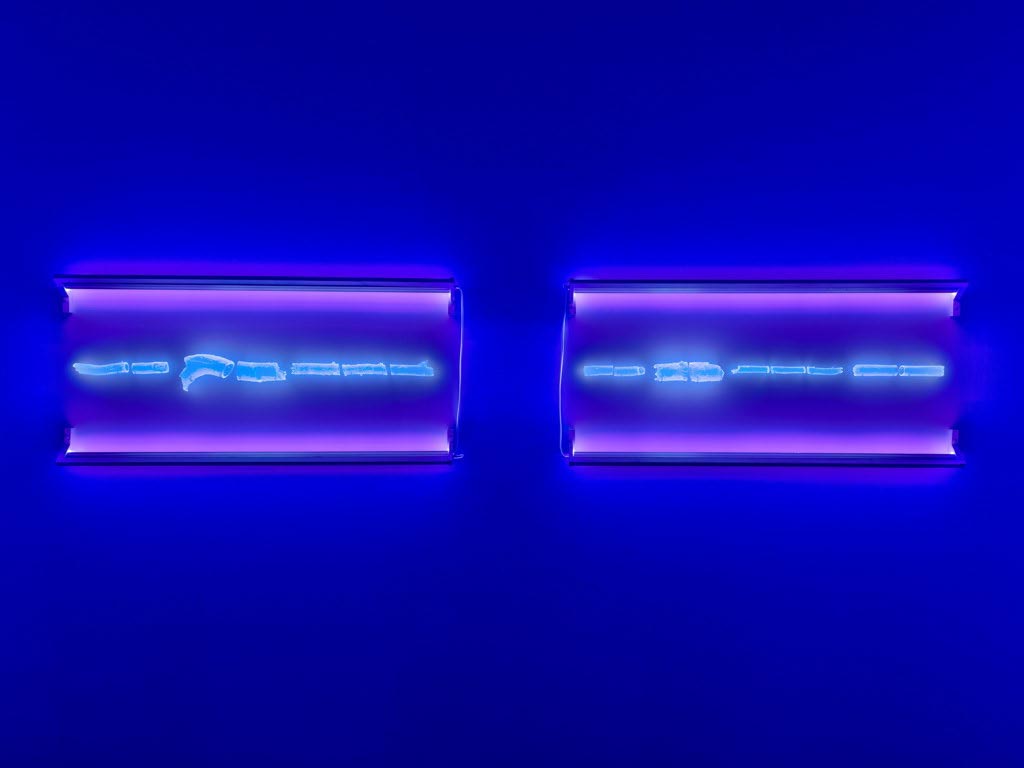

To create Suspended, I visited the tree on daily walks during the height of the pandemic over the span of two years and collected elements left by the tree. Utilizing the round shape of the gallery and a light that wraps the space, I directly reference the process of 3D scanning where the computer captures multiple images of an object using a white flash and a turntable while rotating an object 360 degrees to create a computerized duplicate. The salon style images reference the images that are generated from the scanning process that are used to produce a point cloud to create a 3D model, thus allowing for these models to be replicated as 3D prints. Much like the McDonogh Oak, when an object is 3D printed it is surrounded by a complex system of supports that allow the object to be created by the machine. My work interrogates computerized attempts to replicate this complex and historic piece of nature. Each replica is precariously suspended atop of an oak block mimicking the way the tree’s branches are held up and supported by human mediation on site at City Park.

During a time when the climate continues to rapidly change and a larger acknowledgment of site history comes into sharper focus, Suspended examines what it means to attempt fossilizing nature on a site with a complex past. The continued imperfect attempt of both the artist and computer to reproduce natural ephemera through digital fabrication processes points to our human desire to suspend our impact on what can only exist for a brief moment and confront the realities of the past as we address the present.

While my work to date has explored other species and our declining climate, the work in Suspended has been a gateway in allowing me to make a significant transition in my practice. I am currently working on shifting parts of my practice to focus on my personal family history as important contributors to the civil rights movement in the United States.

My traceable family history begins in the sweeping, flat planes of western Ohio where I am from and where my great-great-grandfather, Reverdy C. Ransom was born shortly before the end of slavery. It is the place where he was raised by his mother who worked in service to affluent white families to provide him an education, and where he later eventually initiated his prolific career as a well known black civil rights activist leader, academic, and eventual Bishop of the A.M.E. church. He was one of the founding orators at the Niagara movement, the forerunner of the now NCAAP, worked with W.E.B. Dubois and acted as the first publisher for Paul Laurence Dunbar’s writings, and later was appointed by President Roosevelt to work within the Office of Civilian Defense. His writings, which explore the continued quest towards equality through the civil rights movement, have been published widely, including his autobiography, The Pilgrimage of Harriet Ransom’s Son. This text in particular explores a pivotal part of his life and career as a student and later academic at Wilberforce University. Reverdy married Emma S. Ransom, my great-great grandmother who also became an activist for black women’s rights. With a YWCA erected in Harlem bearing her name, she was equally important to the fabric of their story and their life’s work.

I am just beginning to work on a new installation and series of sculpture pieces that explore my family history. My upcoming exhibition, titled Arise and Seek, will open at Pitzer College Art Galleries in January 2023, focuses on the timeline of Reverdy and Emma Ransom’s life work as civil rights activists. The exhibition will focus on the Tawawa Chimney Corner House, Ransom’s home located on the Wilberforce (HBCU) campus that is listed National Register of Historic Places and that I am currently working with my family to restore. This space existed as a conduit for progressive civil rights and social justice advocates and initiatives for African Americans. Utilizing historical sites such as the John Brown Fort, removed or altered confederate monuments, and their associated plaques, this exhibition will use redacted and digital replication to question and re-frame the forgotten history of some of our earliest activists like Ransom whose work laid the ground work for civil rights and equality that we are still fighting for today. The title of the exhibition is flexible but in its current state it is a line from Reverdy’s speech the Spirit of John Brown speech given at Harpers Ferry in 1906.

Currently, my work explores human, animal, and environmental relationships through sculptures and installations created using computational processes.

Britt Ransom

What inspired you to get started on this body of work?

I was recently elected to join other members of my family on the Board of Directors of the Reverdy C. and Emma S. Ransom foundation. We are currently working on restoring the Tawawa Chimney Corner House through a grant from the National Park Service as a place to preserve the lifelong legacy and vision of my ancestors, operate as a conduit for advancing civil rights and social justice initiatives, and exist as a learning space adjacent to Wilberfoce University and the Payne Theological Seminary for student scholars and researchers.

This new body of work is inspired by my desire to learn and understand the rich and complex history of my own family. This is a major change in direction for me as I explore my own identity as a mixed person who exists in a world where I largely pass as white. I grew up in a place where racism still deeply persists, where my blackness was often obscured as a protective mechanism, and I finally feel that I am a place in my life and career where I can begin to acknowledge and unpack these traumas through my practice while sharing the important story of my family’s lifelong work towards equality.

Do you work on distinct projects or do you take a broader approach to your practice?

I generally work on individual distinct projects/exhibitions one at a time. My work requires a significant amount of research and collaboration or consultation with scientists, engineers, and historians. I spend a lot of time sketching out ideas, reading, and writing, before I begin work on a new body or trajectory of work. Residencies are also an important part of my process and it is where I am supported in my ability to disconnect from my day to day work as a university professor advising students and fully focus on my own work and practice.

What’s a typical day like in your studio?

My studio recently shifted and is now half in Pittsburgh and the other half in New Orleans. This month I began a position at Carnegie Mellon University where I teach in the Sculpture, Installation, and Site Work area of the School of Art. My academic studio exists on campus in the mix of exciting and always shifting academic environment. While I have my own studio, I primarily work in and out of specialized labs and classrooms where I also teach. I spend time working around students, sharing spaces and equipment to support my practice, and always in a space of learning where I am in constant contact and communication with others.

When I am at home in New Orleans I work primarily in solitude in a small studio building in my backyard. I have my own mini digital fabrication space with 3D printers and CNC machine where I work on the larger construction of many of my pieces. My time in New Orleans is the place where I consider my studio practice to be at home and where I find the most productive elements of my practice and work to take place and where I recharge my ideas and re-connect with the environment.

I do not have a typical day in the studio. My studio processes operate in cycles and are portable. Sometimes my studio is outside at a park with my cell phone or 3D scanner. In other moments my work takes me to a library or archive and all other hours are spent in either of my studios with tools and machines that are the instruments for making my work.

Who are your favorite artists?

One of the most memorable art experiences I have ever had was witnessing Adrian Piper’s Cornered (1988) which was on loan at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago when I was in the MFA program at University of Illinois at Chicago. It was the first time I encountered a piece that caused me to have a visceral reaction and connection to my own racial identity. Adrian Piper has and always will remain one of my favorite artists for that singular life changing moment. My favorite artists list is continuous as I keep learning and being fortunate enough to experience new work. But some long-time and new favorite artists right now are David Bowen, Stephanie Syjuco, Mark Dion, Sadie Barnette, Jackie Sumell, Greg Ito, and Gracelee Lawrence.

Where do you go to discover new artists?

I discover new artists by visiting a lot of museums, galleries, and alternative exhibition spaces. I also attend lectures, zoom talks, read reviews/show announcements, and like many millennials by exploring online.

Learn more about the artist by visiting the following links: