Artist Statement

Nā́rī (2019-Ongoing)

There has always been a sense of legacy being passed among women through the language of embroidery and handcraft, inherited by generations of women and passed along, to break the oppressor by simple but significant hand movements captured on fabric, written in thread.

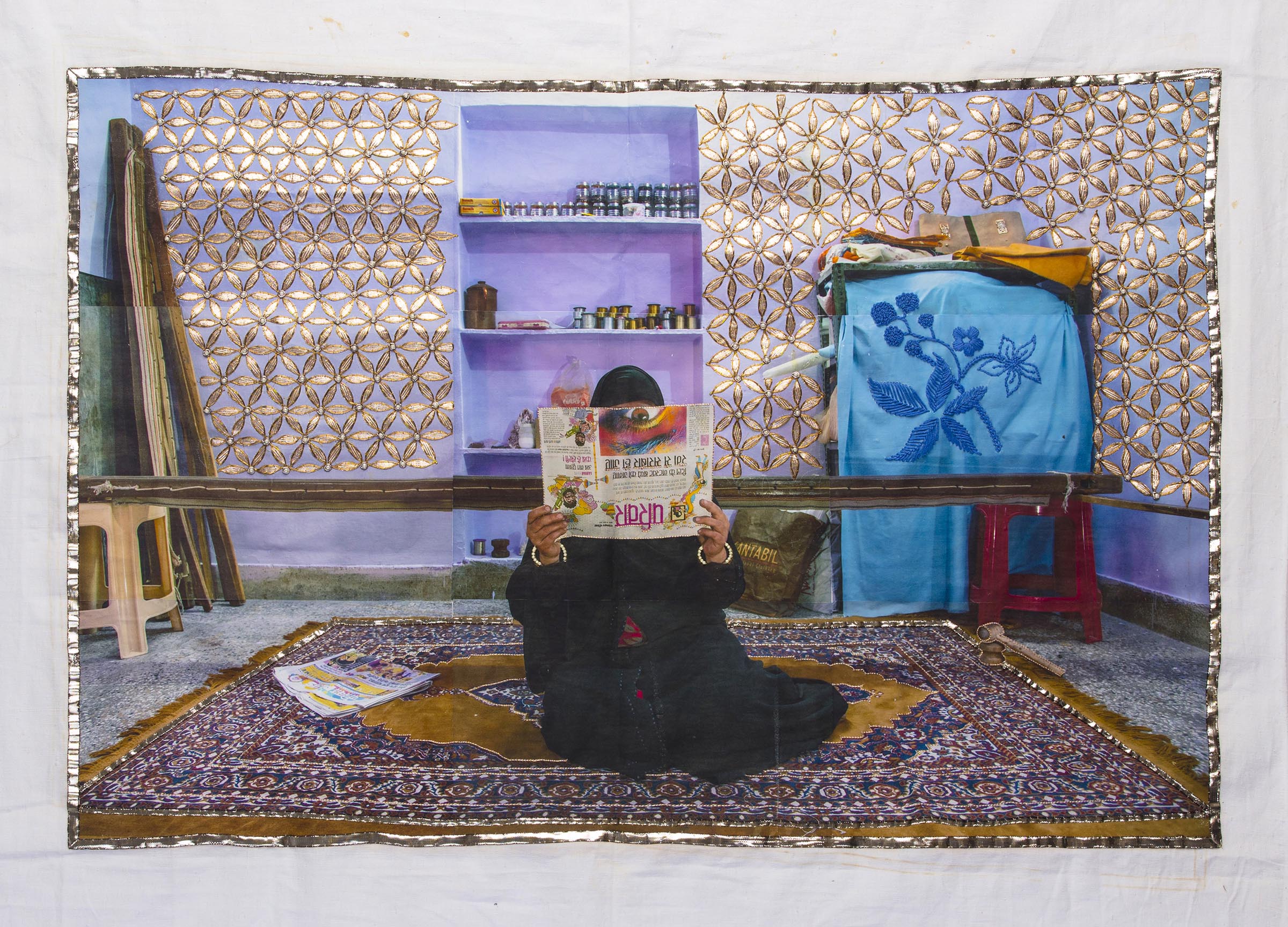

In Sanskrit, nā́rī means woman, wife, female, or an object regarded as feminine but can also mean sacrifice. While misogyny is hardly exclusive to one country, India bears ghastly symptoms of it. While searching for women in India in self-help groups who are learning to embroider, I heard about women who weren’t allowed to come to the centers. They are either not allowed to leave the house, due to their husbands or fathers, or they felt unsafe leaving the house. I traveled to Lucknow, Jaipur, and Chamkaur Sahib where I photographed and interviewed these women about their harsh economic and social realities. Some women talk about their domestic violence.

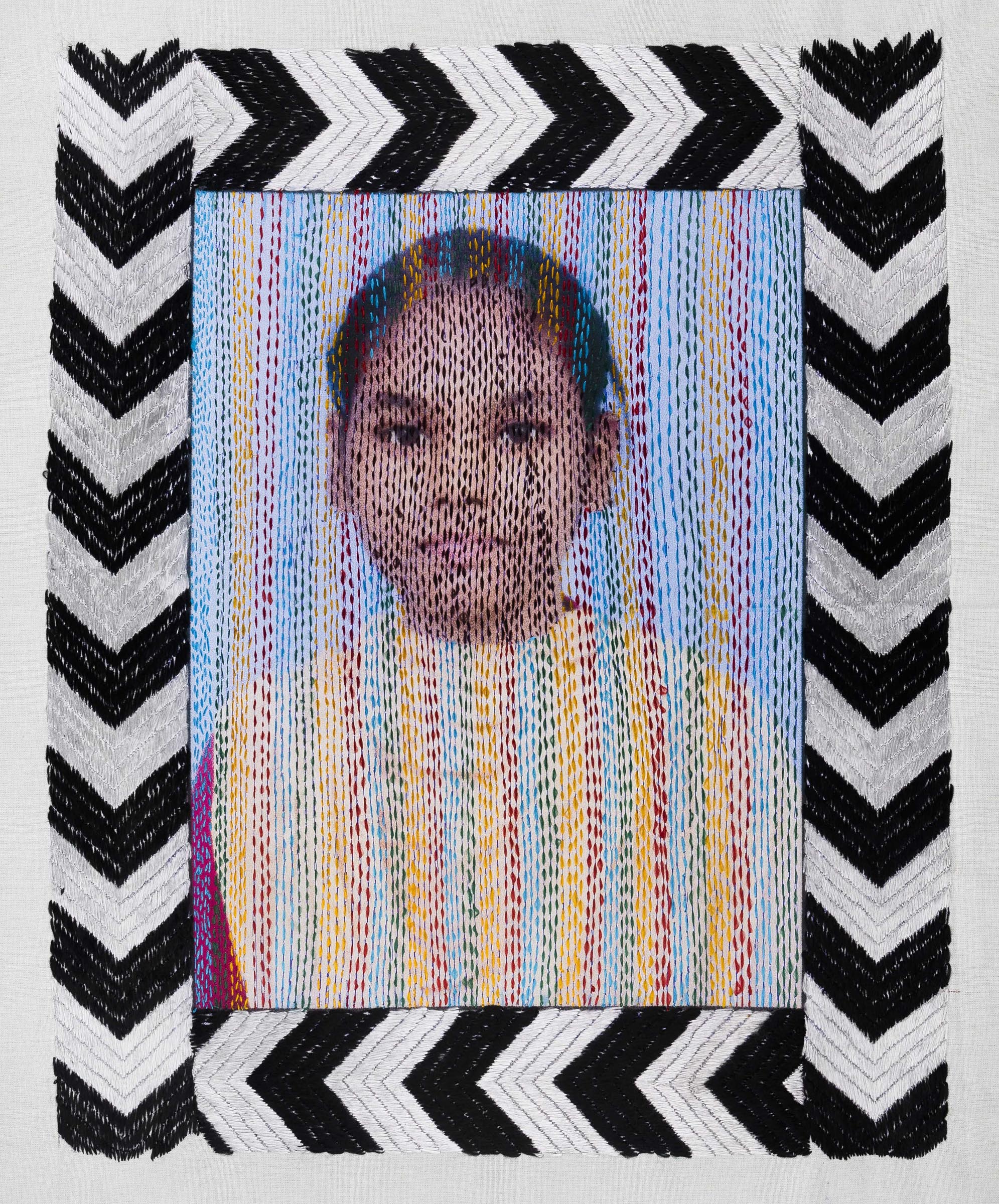

There was a conscious effort in stepping away from the colonized eye in documentary photography of India, and photographing these women in the rooms they live in. I printed the portrait I took, onto the fabric of the region and asked them to embroider the portrait in a way that seemed fit to them, without any guidelines, giving them the agency to have authority over their own portrayal. These artistic collaborations subvert the idea of the artist as the main producer by giving each woman her own creative entity within her own craft. It also engages the problem of representation in portrait photography as addressed by giving women control over their own image.

It is a peculiar sense of belonging and safety found in the private spaces of the unfamiliar. There is an ease in unloading the pain in the agony of another; there is a strange trust and care in these private places, shared by women, known to women. These collaborations created a connection between me and the women in our shared language of art; by listening through our inherited language of embroidery, I learnt the true meaning of nā́rī .

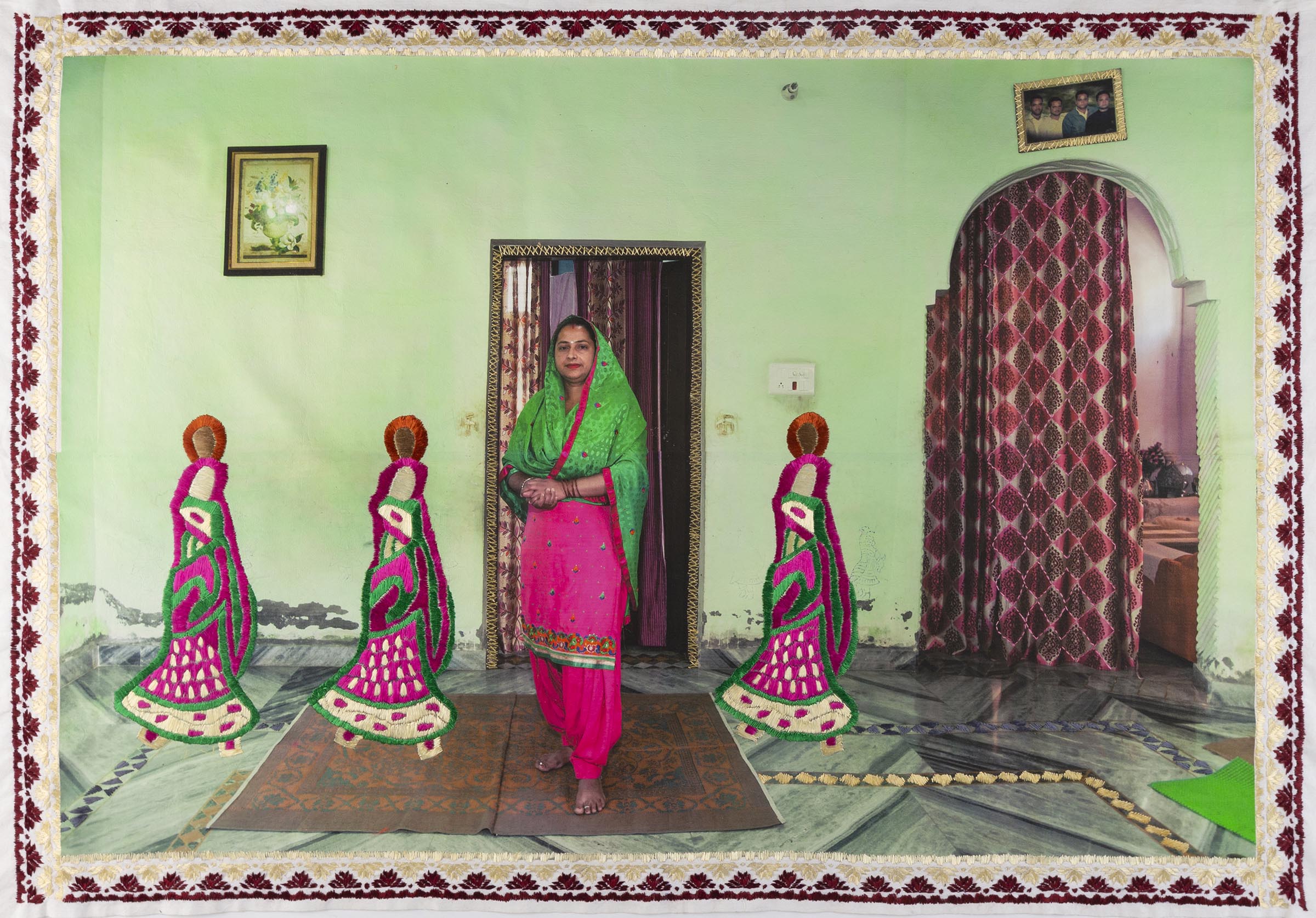

Over the last one year, the community of women whom I've worked with before, came together to collaborate and create ‘Vadhu’ in a disparate world of thought and support during the fragmented times we found ourselves in. We collaborated through international mail and phone calls, but more importantly during the process of creation, we could build a community to support, hear and listen to each other in a different but significant manner, whatever deemed necessary. During these fragmented times, the community of women I work with have gone through mayhem of constant grief and ever changing lives in a pandemic; it became crucial to sustain the community.

While we have talked a lot about change, the kind that was inevitable and the kind of hopeful daydreams, the past and the present have existed and erupted on occasions simultaneously. The women met in their backyards, bringing with them photo albums, mostly wedding photographs and the conversation started; they talked of themselves, the self they saw in the photographs of the past, a narrative of someone transformed as we walked through the memory lanes of many decades. Memories that existed in the photograph, skipped timelines, often jumped, sometimes ground to halt on different occasions informed a new shape of the memory. They embroider the portraits of the past, recalling, recollecting, remembering and reclaiming the narrative of the portrait in sync with the present; the language of embroidery reshapes the memory of the photograph.