How did you get into making art?

Through the circuitous path! When I was young I sought out strange movies and experimental music, but I didn’t have any notion of what I was good at. I wanted to be Gregor Mendel, or Francis Bacon, or Marie Curie, or John Waters. I went to college without really knowing why, so I tried lots of things, switched schools and majors a few times, took time off, and eventually landed in art. I had an old copy of Gardner’s “Art Through the Ages,” and found art history to be a beautiful lens to understand our world. I realized making art could act as a funnel for all of my interests, and once I found the darkroom my search was over.

What are you currently working on?

I’m working on a kind of advancement of the floral portraits I make for “The Wild Beasts.” That project is continuous, but I wanted to dive deeper into specific aspects of plants and flowers. There are rich stories to be told about the evolution of plants and how humans intersect with them, so I’m thinking of this new project as a visual narrative of the history of botanical life. Back to that lens of art history—flowers are on ancient Egyptian tombs, are some of the earliest subjects of Chinese paintings, are woven into medieval European tapestries, become decorative motifs for Rococo walls . . . they are powerful objects that we have gravitated towards for millennia.

I’m thinking of this new project as a visual narrative of the history of botanical life.

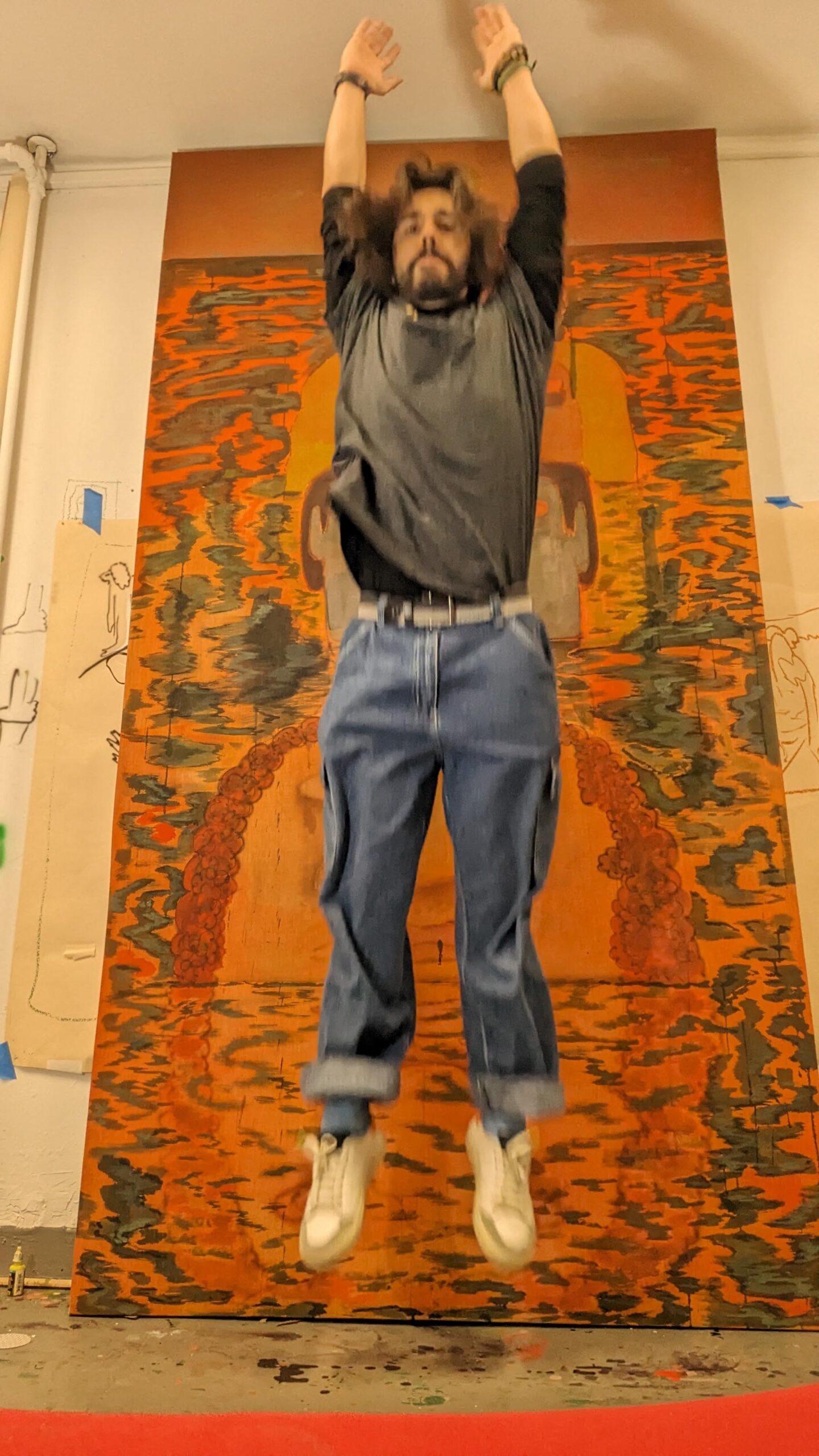

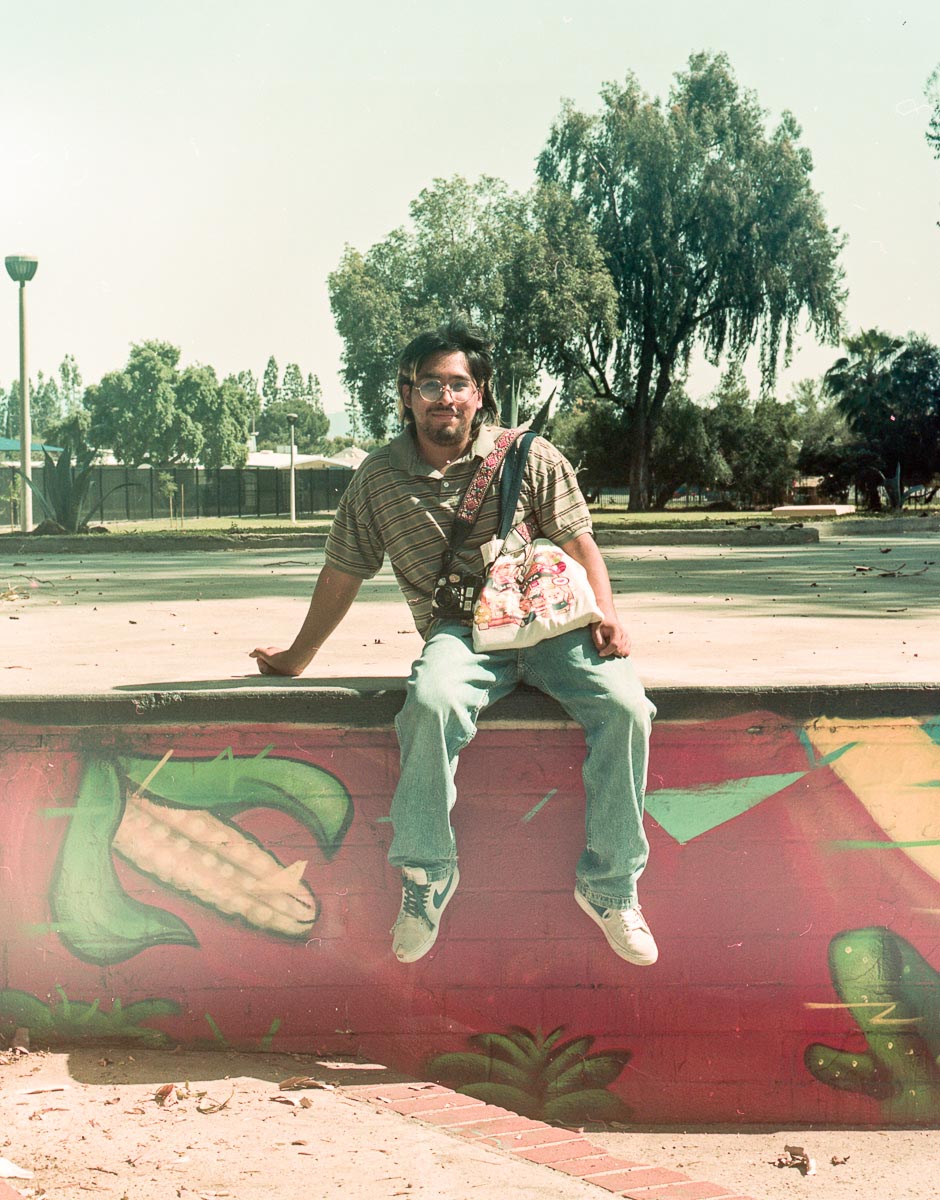

Peter Cochrane

What inspired you to get started on this body of work?

My interest in botany started somewhere in my teenage years. “The Wild Beasts” is full of codes that point to specific biological and social implications of plants, which I use to add dimension to the personality of the subject. The more I worked to insert little secrets through my choice of flowers, the more I realized I wanted to share botanical history in a more explicit way. I like to think of photographs as movies—they’re still images, but what’s happening inside and outside of the frame? What led up to the creation of an image, and what will come after? What is the lore behind each component part that makes up the totality of the picture?

I think of what’s in frame as a set piece where each object is used to build the story of the whole, leading to a larger idea that expands far beyond the frame. One of these new images is of dozens of Magnolia grandiflora blossoms in states of explosive life and withered death. Magnolias grow all over and are comprised of hundreds of species, but they’re also one of the oldest flowering trees at around 95 million years old. The magnolia existed alongside dinosaurs and before bees, so it needed to be pollinated by beetles. Fascinating! As I’m arranging flowers and moving around lights to make an image, I like to imagine what a grove of ancient magnolias sounded like blowing in a storm, or what the light looked like as a comet crept in front of the sun.

Do you work on distinct projects or do you take a broader approach to your practice?

I work almost exclusively in distinct projects. I like to have several going at a time, as well. I pick up a thread of an idea and let it bounce around for a while. I’ll read about it, watch films about it, go on walks about it, and if it’s something that keeps waking me up at night I’ll start piecing it together in visual terms. I’d say that most of the final images I make are first built in my mind. Then, through a bit of fussing about with materials or talking through the ideas with specialists, I’ll begin constructing photographs or artworks that all relate to the larger theme. It’s a bit like tuning a radio—I know I’m looking for something specific, and with enough tinkering, patience, and action it becomes clear.

I enjoy thinking about work in this longform, background processing way because it allows me to place pieces of the puzzle as they come. For example, when I was formulating the idea of making portraits out of flower arrangements, I knew I wanted bombastic imagery full of life and color, as I had come out of years of making tonally dark work. One day, I was walking through an exhibition of Fauvism at the National Gallery of Art in DC while thinking about the bold personalities of my friends and mentors for whom I was making these portraits. I knew about this group of painters but I hadn’t known the source of the name until I read that “les Fauves” translates to “the wild beast.” Their loud colors and artistic kinship clicked with what I was feeling for my friends, and on a personal level I loved that the term had been hurled at these early 20th-century artists in a critically derisive way, yet we now admire their leap out of Impressionism. This method of working towards a distinct goal lets me constantly build towards it as I move through the world.

What’s a typical day like in your studio?

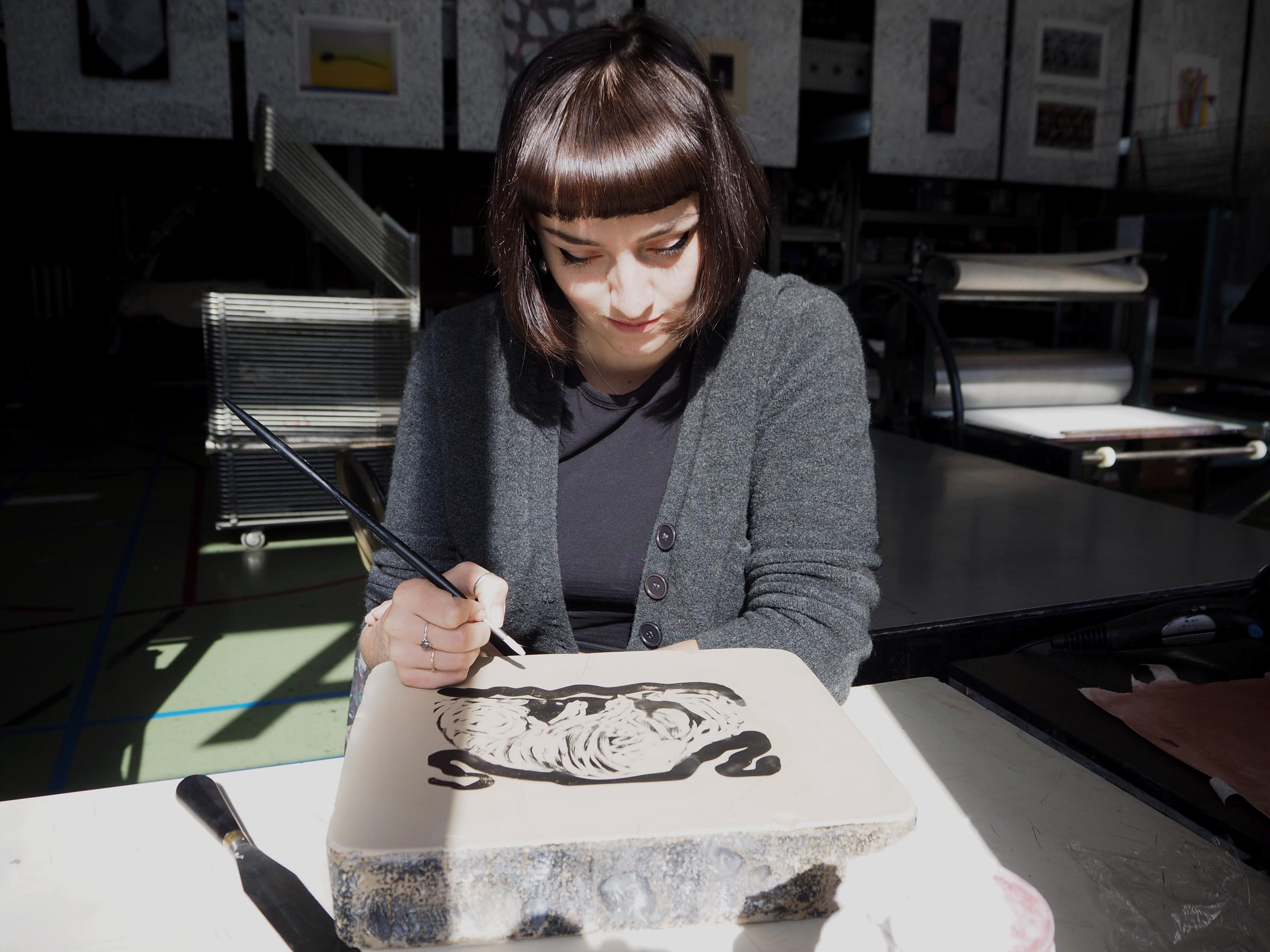

After about a decade of making fine art prints for artists, galleries, and museums, I decided to open my own print studio called Threep. I was able to add to archival inkjet printing by also helping artists take their non-photographic works to prints. I have this lovely mix of work going on under the umbrella of my studio. Days are divided up between client jobs and my own studio practice. Sometimes it’s photographing an artist’s piece and making test prints before moving on to an editioned run of prints, while others it’s a full day of building out a still life for my new body of work, testing out new materials, or doing admin on the computer.

Who are your favorite artists?

This is constantly in flux, of course, but I often think of artists who work with ephemeral qualities, such as the Light and Space artists, Wolfgang Laib, Barbara Kasten, Olafur Eliasson, Chiharu Shiota, Rachel Whiteread, Louise Bourgeois, Nick Cave. I suppose I’m drawn to all-encompassing experiences. I also consider myself very fortunate to have worked for Catherine Wagner in my twenties and saw firsthand what goes into being a working artist.

Where do you go to discover new artists?

Lasting impressions are always made in person, but I do subscribe to many gallery and museum email blasts for their updates.

Learn more about the artist by visiting the following links: