How did you get into making art?

I have always been drawn to making things—writing, drawing, sewing, building, collaging, photographing—since as young as I can remember. There is something in the tactile experience of making that has held my attention for decades, even though my approach to materiality has changed over time. But I think the most instructive entry point into making art took place for me in community college. Being surrounded by multigenerational artists, retirees, and professors who built their studios to function as a cross between therapy and art practice deeply informed my life. While receiving BFA and MFA degrees were pivotal, it was the support from my early mentors, conversations with artists four times my age, and shared meals over calloused hands that had the most to do with understanding the potential of art to form a community—for the possibility of artists to be in dialogue with each other.

What are you currently working on?

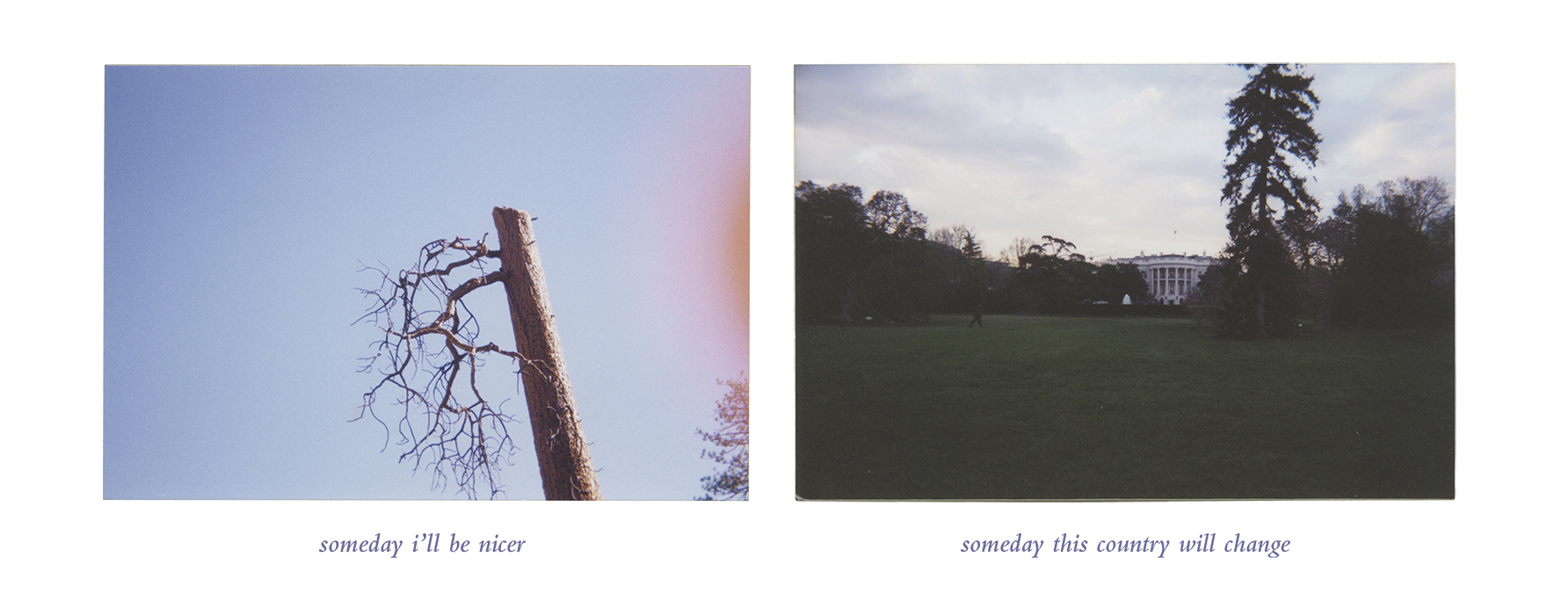

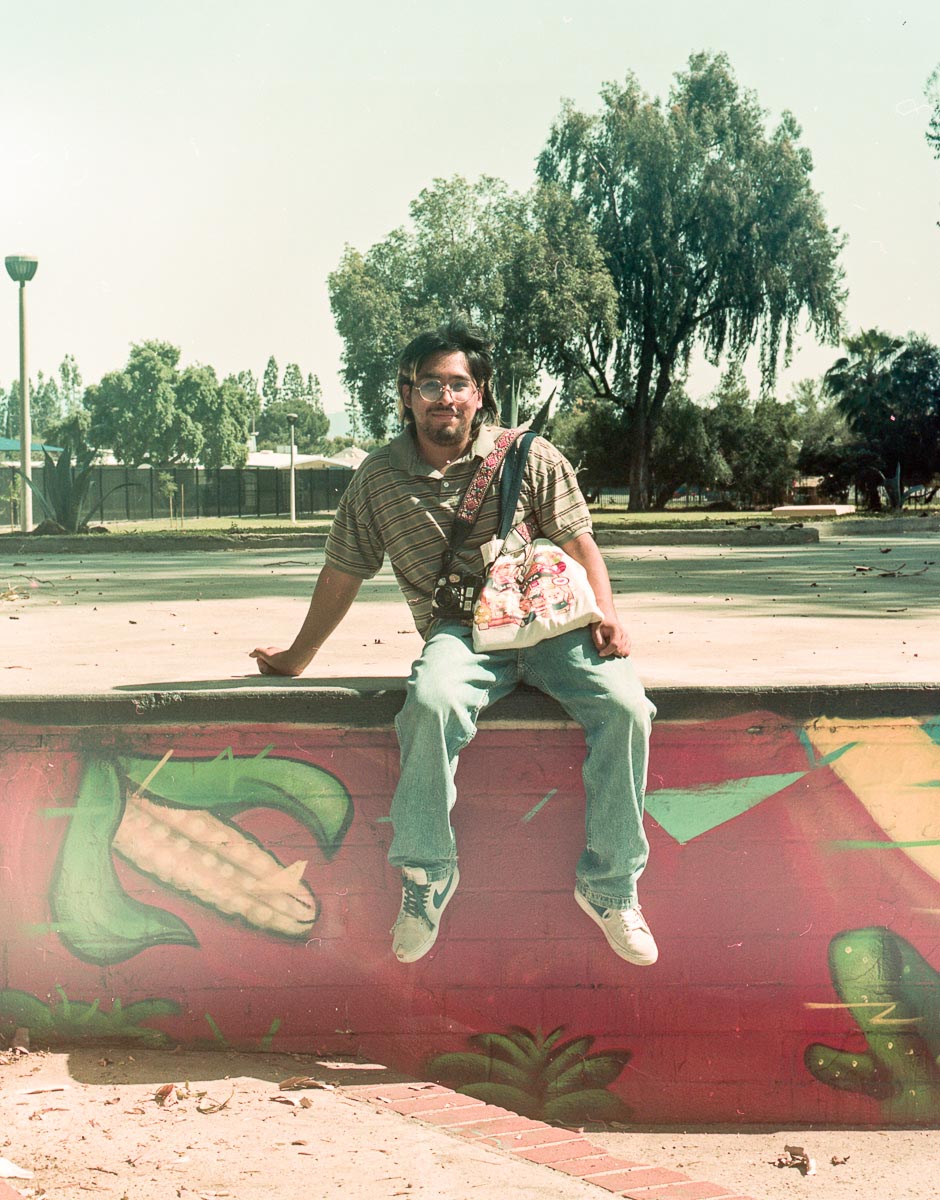

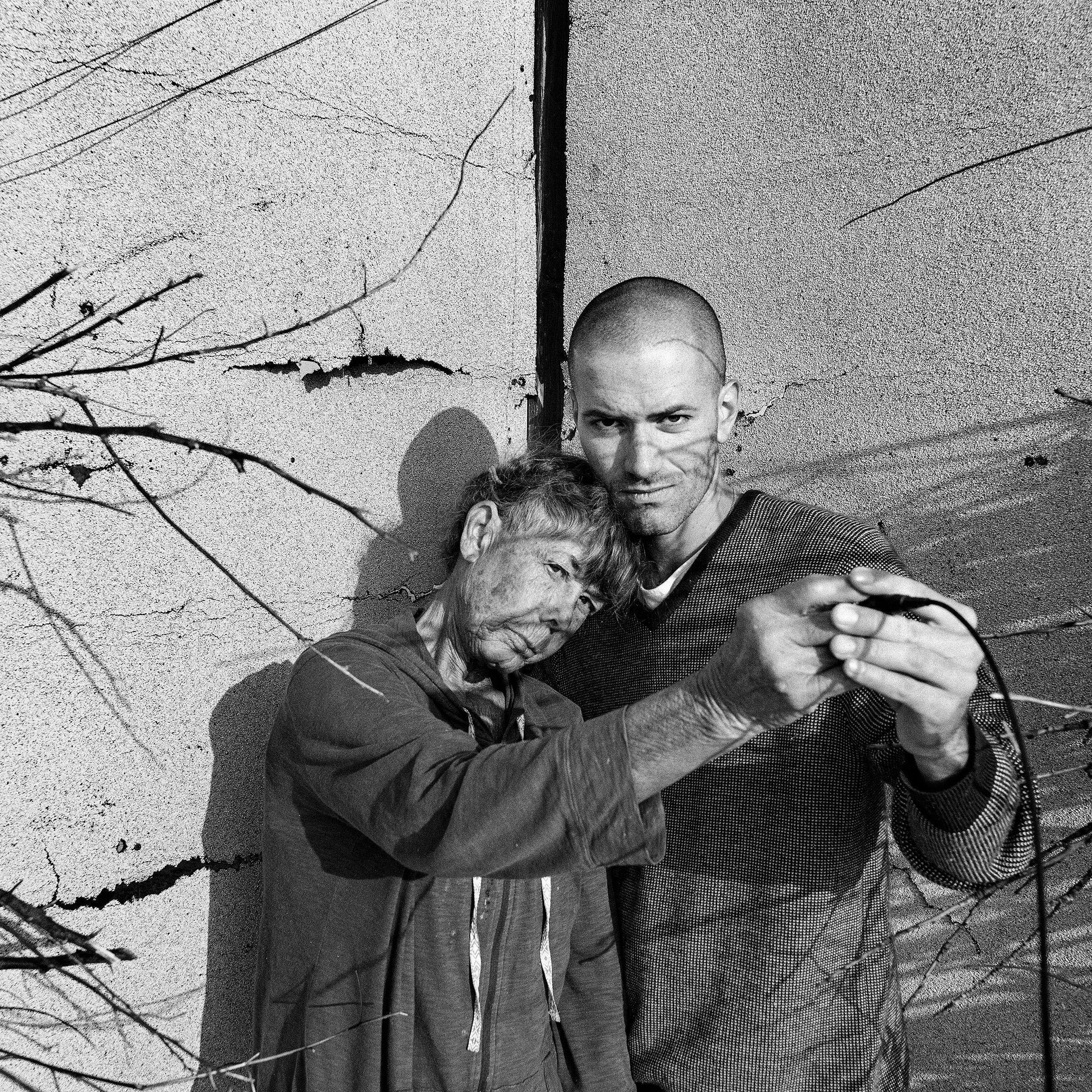

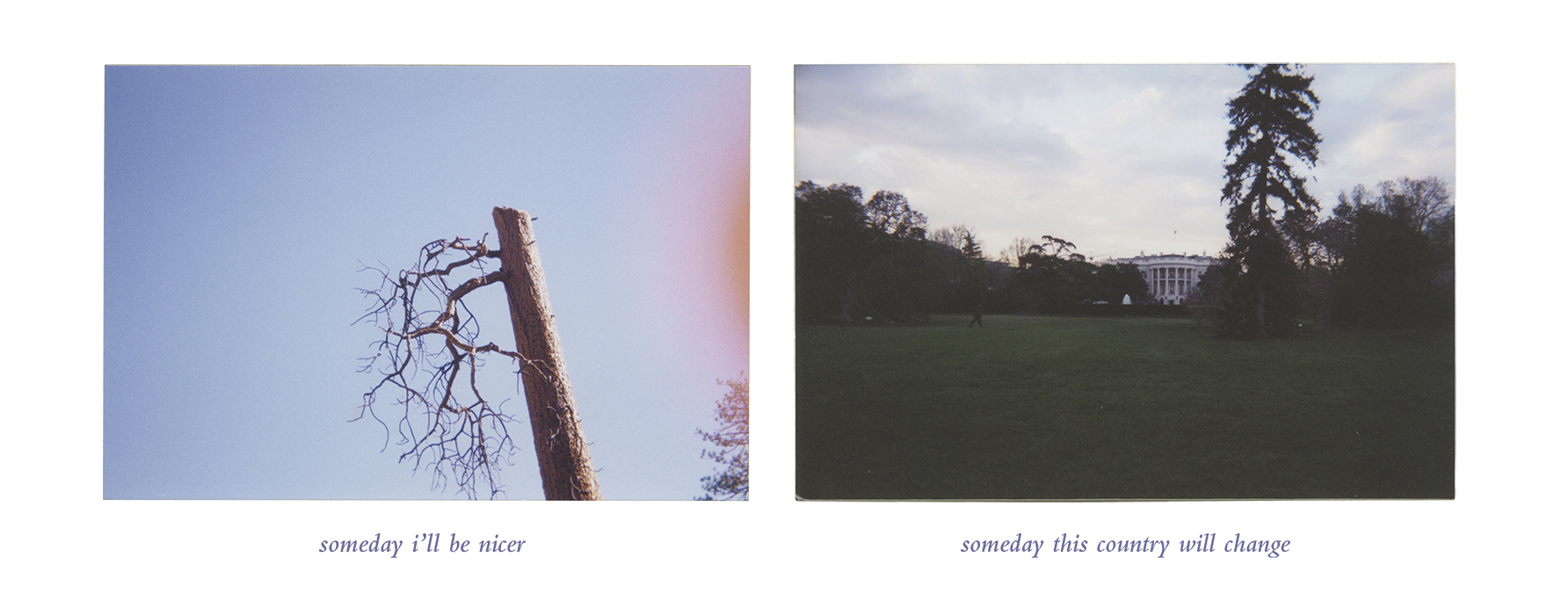

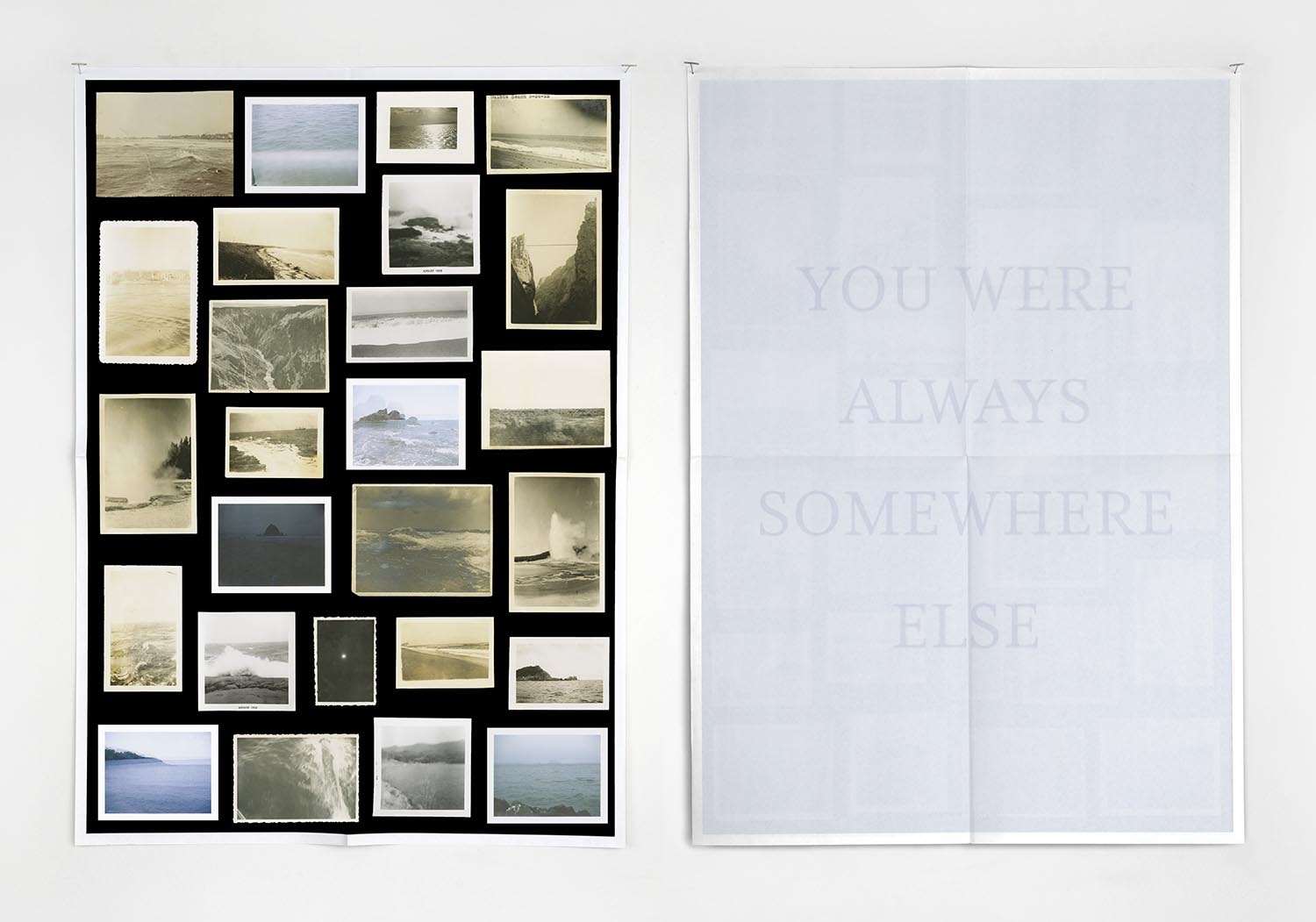

I’m currently working on a new project, Stratagems (Orange County), which considers Orange County, California’s history of landholdings, subdivisions, conservatism, and underrepresented narratives through the lens of being a multiracial Xicana and a transracial adoptee. Sourcing from regional archives in CA, my project maps autobiographical and historical accounts, situated in the double-lens of otherness inherent to adoption and mixed-race experiences. I’m interested in making a reimagined archive that reflects on growing up in OC post-Reagan while critiquing the history of anti-Mexican sentiments prominent in California and contextualized by Gloria Anzaldúa’s, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, among others. While writing encompasses most of my work, it functions as a central component of this project, culminating in an artist book, multi-channel video, works on paper, ephemera, and installation. In addition to my ongoing project, I’m working on a text/image piece for the Daily Trumpet [@dailytrumpet], organized by Jonathan Horowitz in response to the erosion of democratic values and the rise of intolerance in the wake of Donald Trump’s presidency. Pulling from imperfect Kodak disposable film photographs I took in Washington, D.C., in 2002, my text/image combinations reflect the palpable tension playing out in today’s society. Specifically, the work addresses the psychology of microaggressions and the negative impact of both microaggressions and macroaggressions on Black, Indigenous, and people of color—no matter how much some wish to discredit these experiences. In a moment when the president has issued an executive order conflating anti-racism with anti-Americanism, I am reminded that anger, protest, and dissent are more than justified responses. By pairing these images with text punctuated by the subjunctive mood, “someday” solicits a different future, one in which these acts of aggression no longer mark our daily experience.

What inspired you to get started on this body of work?

My relationship to home, place, and space inspired this inquiry into Orange County. Usually, my work responds to environments I inhabit and the interpersonal relationships that texture these places/spaces. More recently, I’ve been working from archives—found, historical, and familial—to explore metaphors through writing and image-making. For Stratagems, these approaches are merging. I’ve wanted to make something about California for a long time, as it continues to be home despite relocating to the east coast in 2015. But it’s impossible to situate Southern California in my work without confronting the complexity of what it means to be from there—what it meant to grow up in a place that provided unyielding disapproval of being any shade of brown. While language is always highly considered and utilized in my work, I’m only now finding a way to articulate the relevance of OC’s painful history. Thanks in part to Bradley Onishi’s podcast, The Orange Wave: A History of the Religious Right Since 1960, Gustavo Arellano’s journalism, and the University of California Irvine’s Orange County & Southeast Asian Archive Center with support from curators and research librarians, Thuy Vo Dang and Krystal Tribbett.

Do you work on distinct projects or do you take a broader approach to your practice?

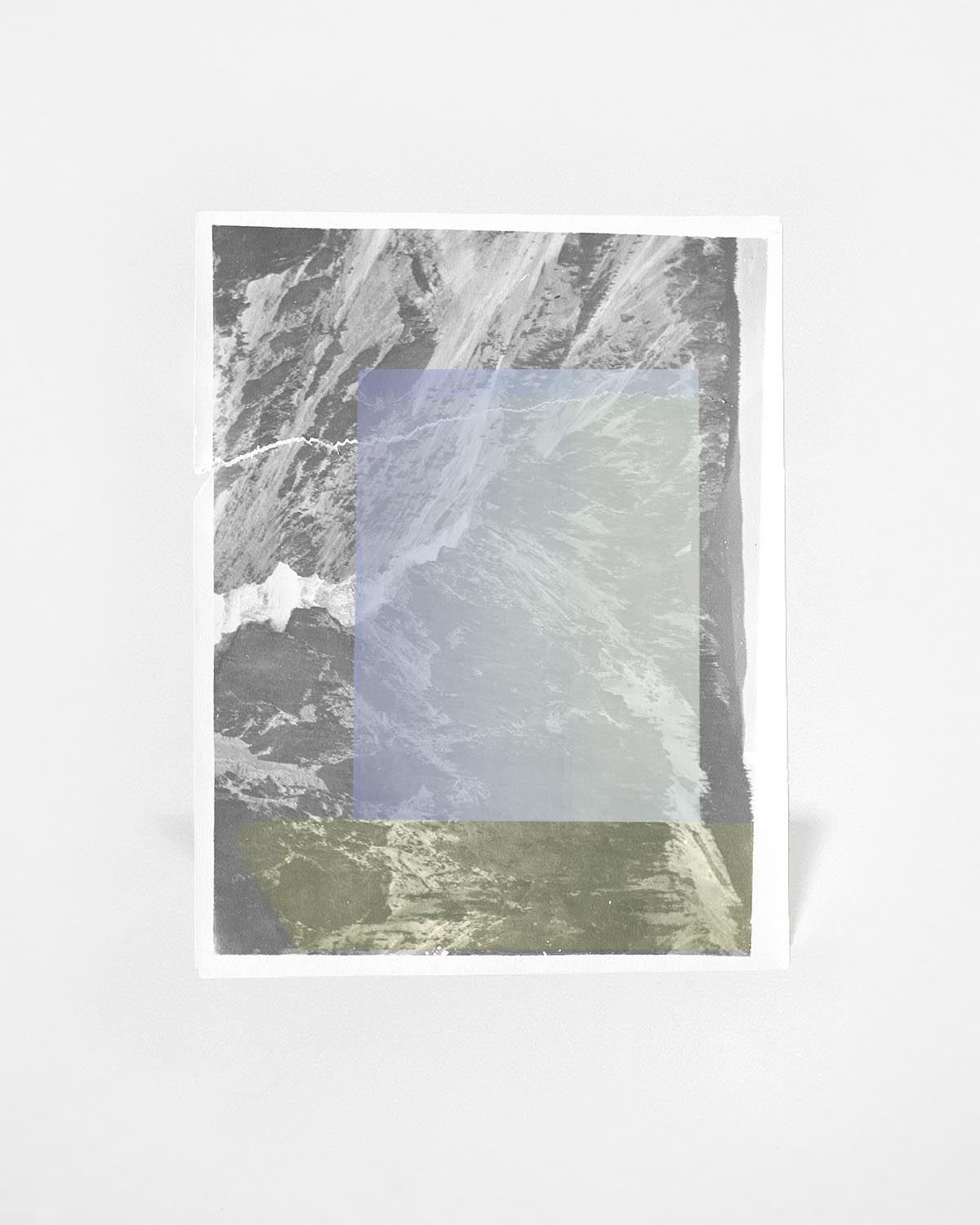

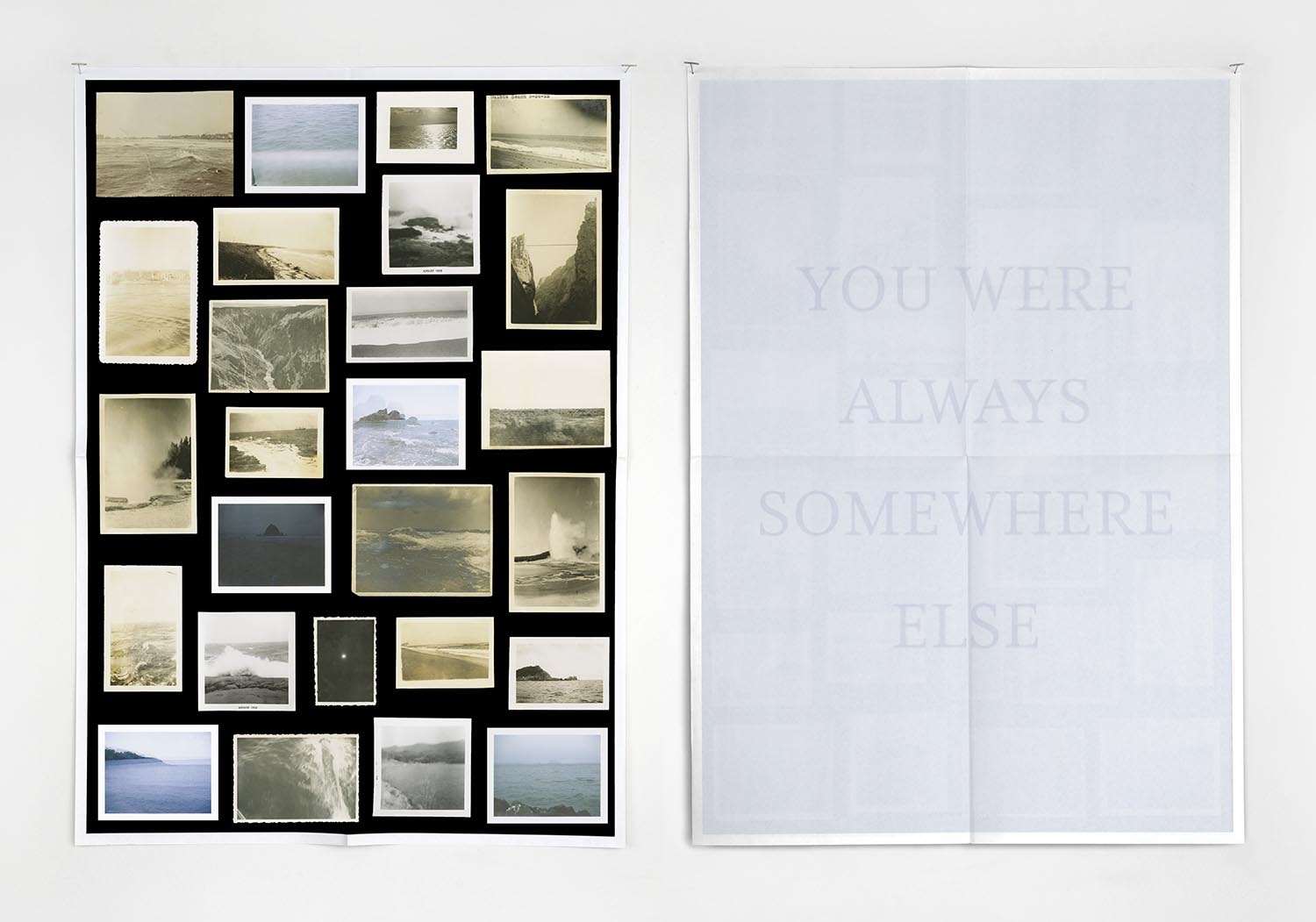

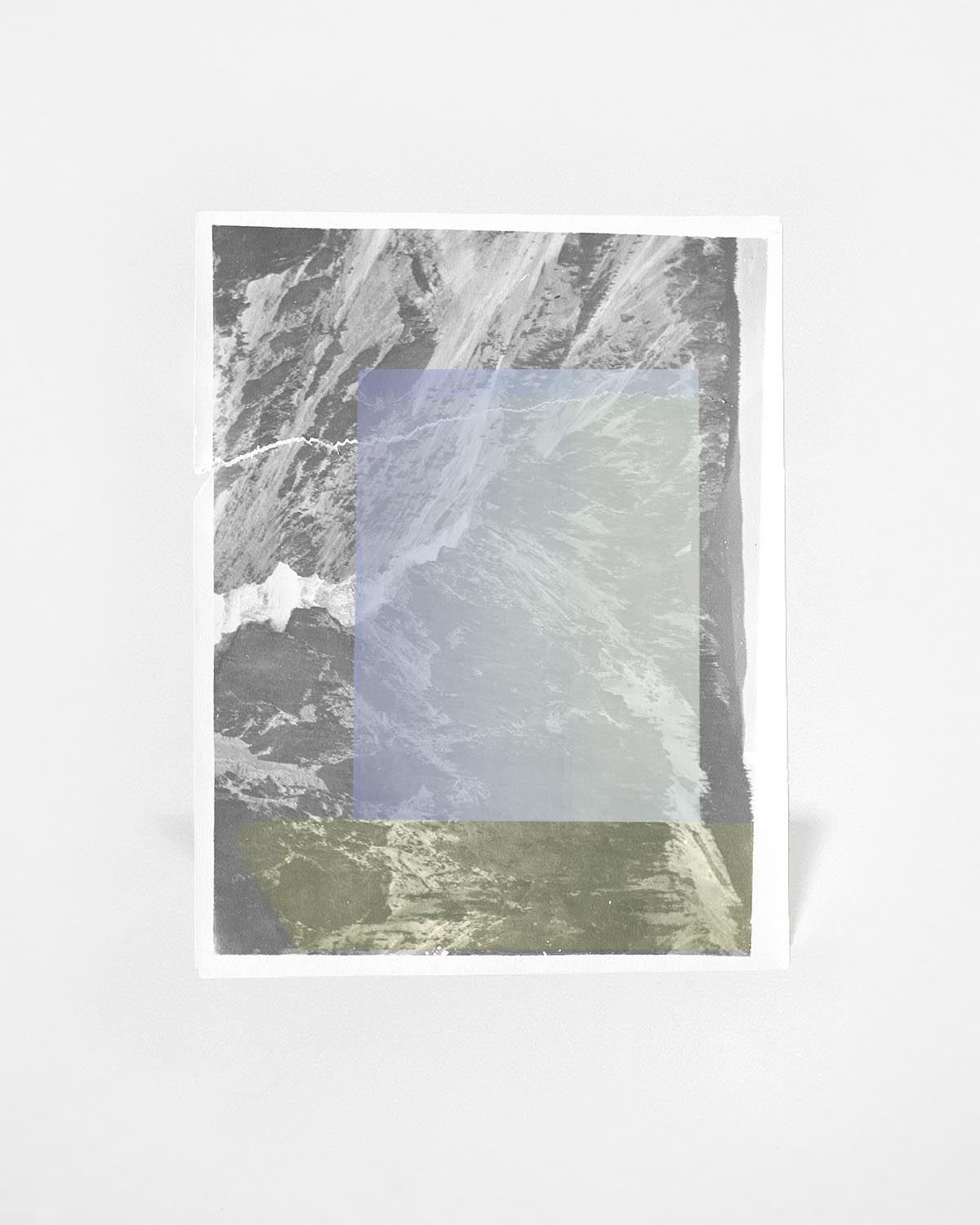

For the most part, I work on distinct projects, but often they intersect with one another. Intertextuality is woven through each body of work; although subtle, I see every project as interconnected. The common thread of my work is grounded in disorientation, which has taken several shapes over the years, spanning my former studio in the arts district of Los Angeles, the Sixth Street Viaduct in LA, various sites in Philadelphia, New Jersey, and archives from Mancos, CO, plus a smattering of found images from the US and beyond—many of which position the sites in relation to subjects who stand in as characters sourced from my life. Historically, each site has been about rupturing seeing and perception, using images that could be alluring only to contaminate them with language that speaks otherwise. So this approach to dislocating one’s vision is an underpinning to how I work across media in an attempt to puncture a sense of concrete time and space—both cognitive and embodied.

What’s a typical day like in your studio?

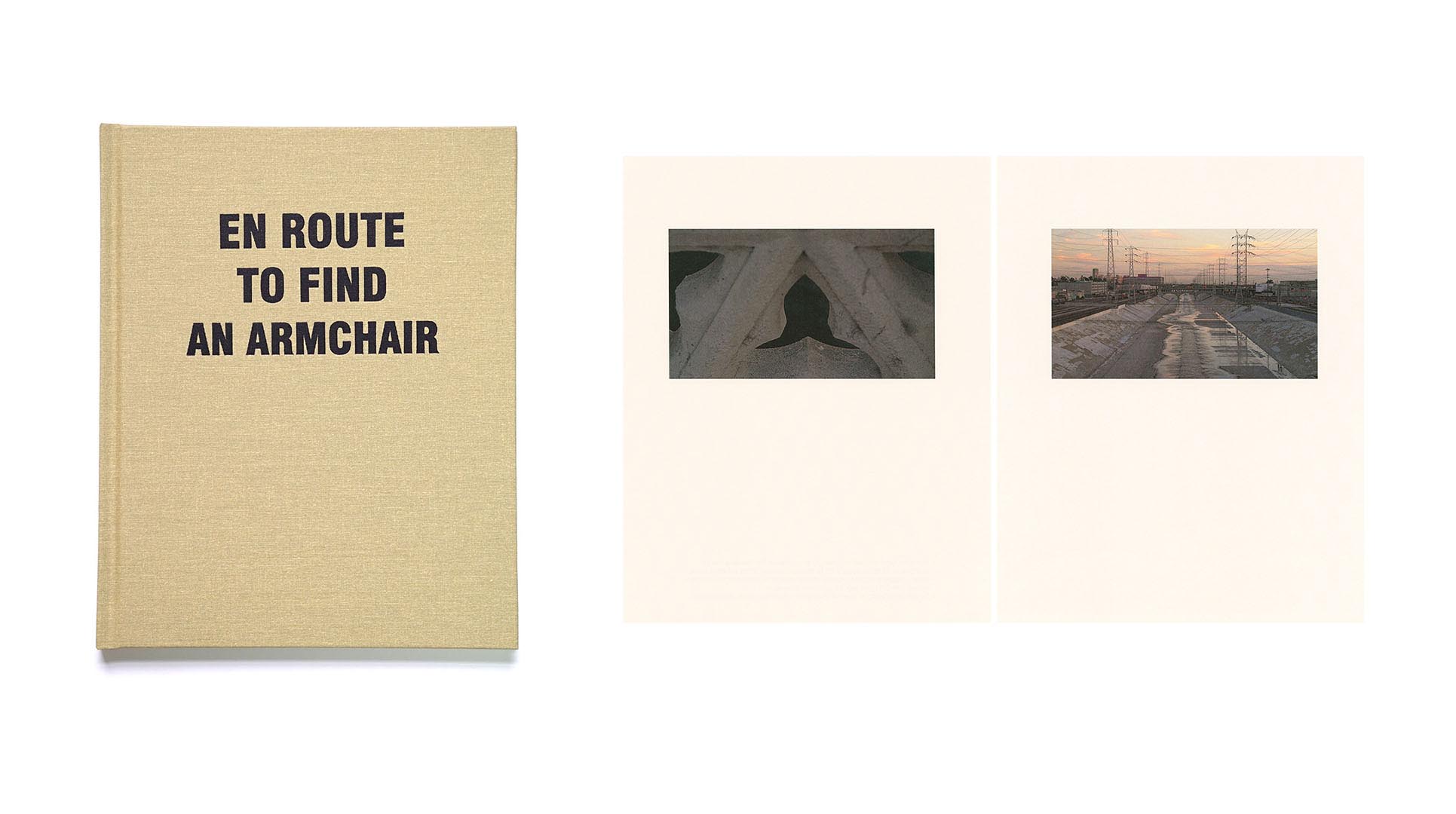

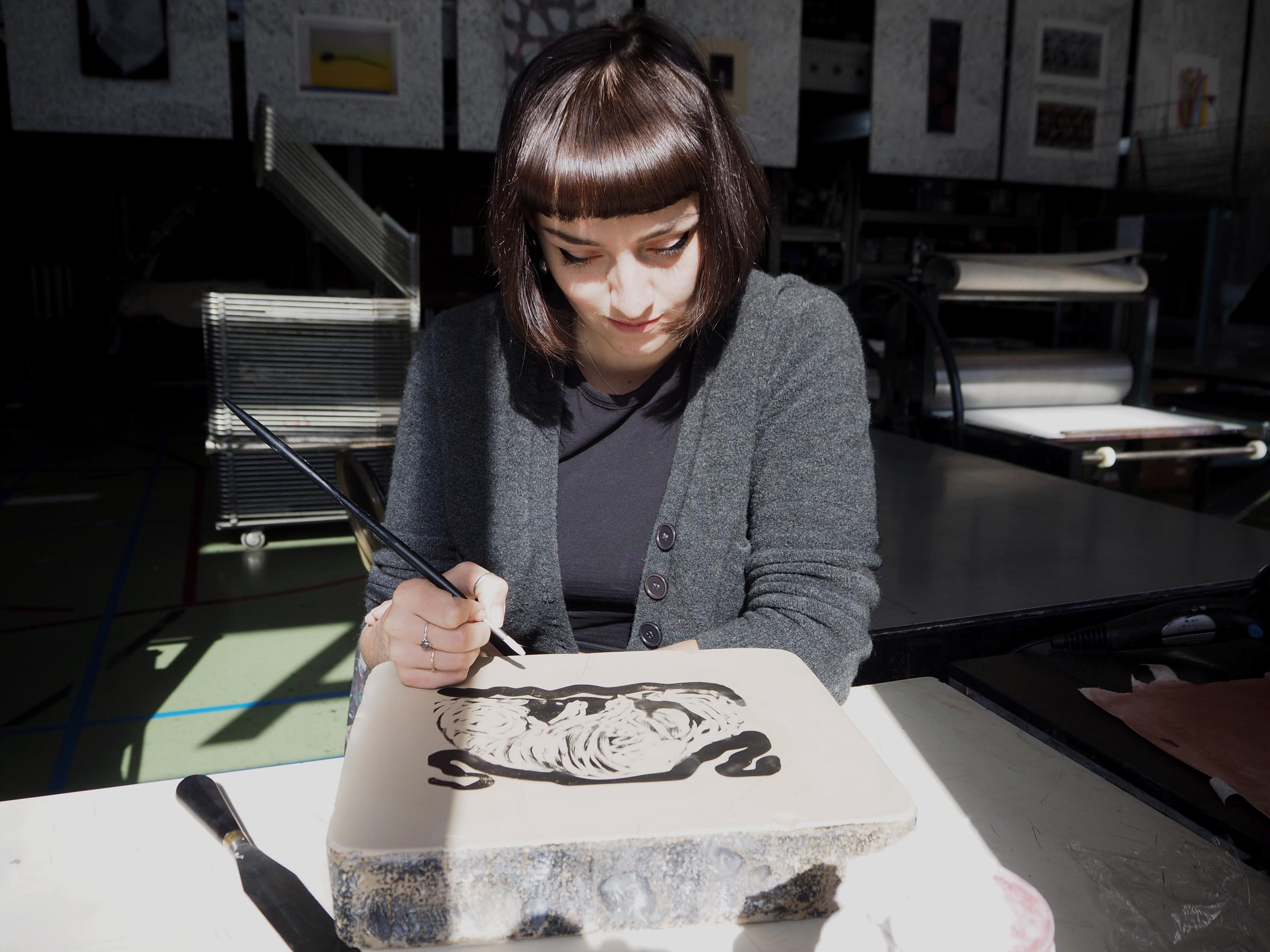

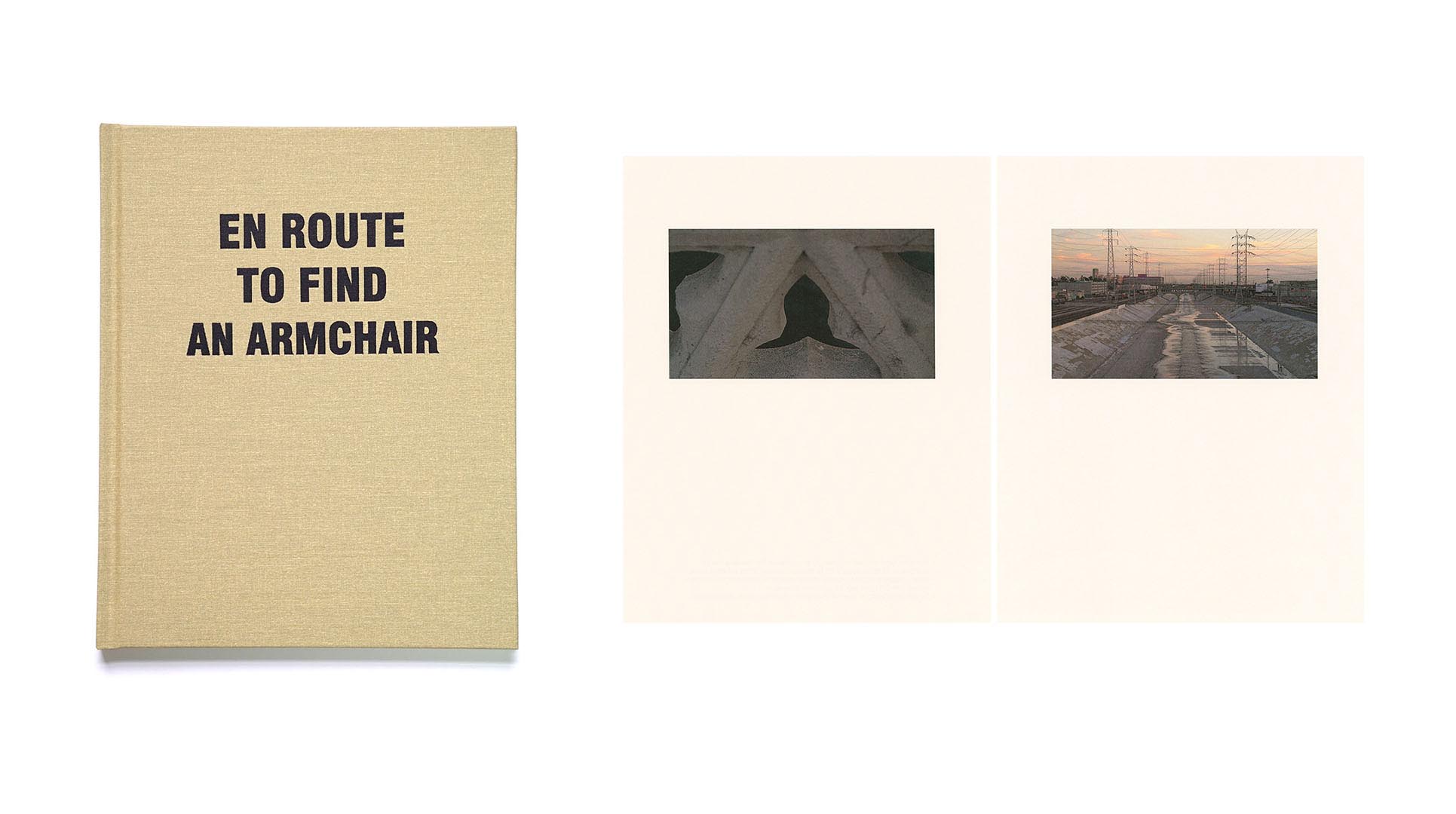

I work in different patterns throughout a year, so a typical day varies depending on the season. My approach to making happens in bursts, usually centered around the production of a new publication, works on paper, and occasionally an installation. For most of the year, a typical day in the studio includes reading, research, writing, and postproduction to edit, develop, scan, and sequence photographs, prints, and moving images. But for the other part of the year that is more materially-driven, I’m usually on-site somewhere photographing, shooting video, screen printing, or working from an archive. I’m a printmaker by training, but my work sits at the intersection of print media and lens-based media and heavily relies on the role of the lens; the latter has shifted my studio time to be reliant on a screen, mediating the physical process of print more intermittently. My time is also structured by running my independent artists’ books and publications project, Seaton Street Press, which includes collaborating with artists and institutions. Lately, in addition to adjusting to the pandemic, I spend my time writing, reading, and listening to a podcast while moving images around.

Who are your favorite artists?

Leslie Hewitt, Basim Magdy, Moyra Davey, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Laida Lertxundi, R.H. Quaytman, EJ Hill, Zoe Leonard, Rinko Kawauchi, Penelope Umbrico, Lisa Oppenheim, Nancy Davenport, Lygia Clark, and Doris Salcedo to name a few.

I have always been drawn to making things

Lindsay Buchman

Where do you go to discover new artists?

Art book fairs are the primary places I see and learn about artists, writers, and collaborative projects. As an independent publisher, I greatly value the art book community, and the role of Printed Matter, Chicago Art Book Fair, Vancouver Art Book Fair, and many more. Residencies also provide an engaging way to meet new artists. I spent last summer at the Wassaic Project, and it was inspiring to meet so many incredible people there. Also, publishing platforms like Bomb Magazine, Hyperallergic, and e-flux are places I turn to regularly. Additionally, I teach at Skidmore College, where I utilize the Tang Museum’s public programming and collections, which are excellent resources, too.

Lindsay Buchman is an artist based in Philadelphia who was recently shortlisted for The Hopper Prize. To learn more about the artist: