How did you get into making art?

I’ve been making art for as long as I can remember – collage, piecework, sewing, weaving. I was one of those lucky kids who grew up with parents who encouraged and supported me to take my “hobbies” as seriously as my education. In the early 2010s living in Río Negro, Argentina, I fell in with practicing artists – sculptors, painters, and many, many fiber artists. It was all over for me! My university education in literature combined with the hand/heart education I had gained from spending so many countless hours in the arms of women textile practitioners (have you ever learned how to knit? Thread a needle? It’s amazingly intimate to have someone’s breath hot on your cheek, their hands holding your own, guiding, teaching by moving together). While living in Argentina, one of these artists, Mary Coronado, a Mapuche-Argentine weaver, mentored me, taught me through a year of weaving together at her loom to ask the questions I wanted to spend a lifetime exploring: Who owns a story? Who gets to tell it? And is the oldest human longing, as Zora Neale Hurston claims in Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), to have one’s own story heard?

What are you currently working on?

Just before the pandemic hit, I began a new research project, thinking through the visual history of Mexican artist, model, and storyteller Luz Jiménez (1897-1965) and her weavings, as documented in the paintings and photographs of Jean Charlot, Diego Rivera, Fernando Leal, Tina Modotti, and others of the Mexican modernist school. In a 2000 exhibition co-sponsored by the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes (Mexico) and the Mexic-Arte Museum (US), the significance of Luz Jiménez (1897-1965) on Mexican art was given international attention. Yet, despite this exhibition, her work as an artist remains unacknowledged. She continues to be seen as the “muse and model” for other artists, as stated in the 2000 exhibition title. Instead, how does Jiménez leverage this platform of model and muse, to create her own art practice of performing and preserving Mexican-Nahua indigeneity through weaving, as well as written and embodied storytelling?

What inspired you to get started on this body of work?

Working with Mary Coronado in Argentina, what struck me principally was the idea that to weave as a tribally-enrolled or unenrolled ethnically indigenous woman, is to perform an identity. She was perceived as “more Mapuche” at her loom, as embodying Mapuche-ness regardless of her spoken language (Spanish) or her familial or cultural upbringing. The Argentine government funded the art collective she helped organize because they were preserving Mapuche identity through teaching and reclaiming Mapuche arts. This tension between performing and preserving a cultural identity is a tension I have lived and will continue to live. As a child of (im)migrant parents, I have seen in one or two generations, cultural touchpoints disappear, reinvent themselves, and doggedly persist. To perform or preserve an identity is not a tension between falsifying and truth-telling, but a both/and strategy to make sense of one’s story in a larger web of historical and contemporary non-neutral circumstances. I am drawn to someone like Luz Jiménez then who lived in this tension, who played with her audience’s perceptions of her, and in that play, perhaps found not just herself, but the way she wanted to tie her story, her people, her history in Milpa Alta, D.F., Mexico to the larger and enduring history of the revolution and Mexican modernist art.

This tension between performing and preserving a cultural identity is a tension I have lived and will continue to live.

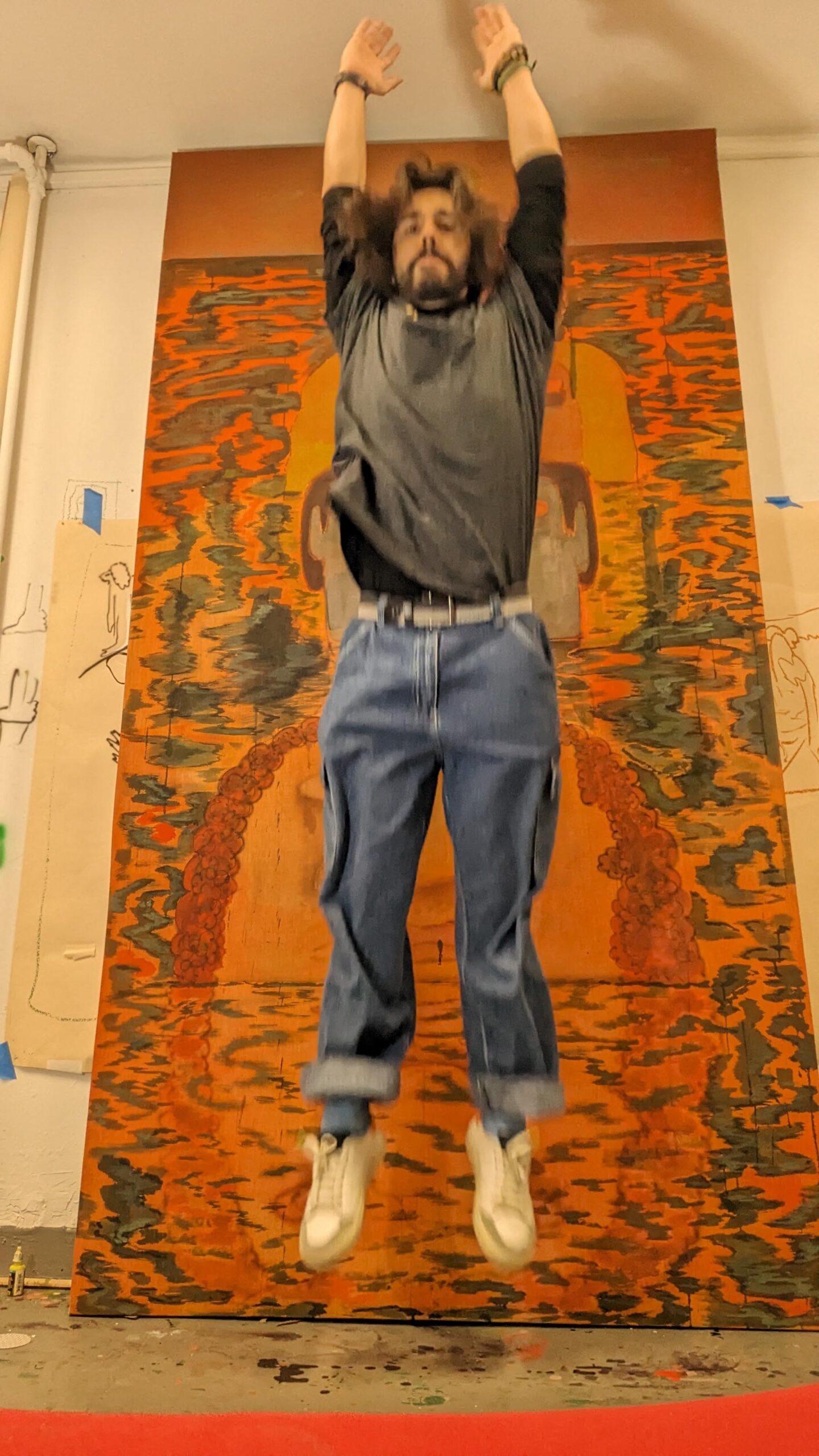

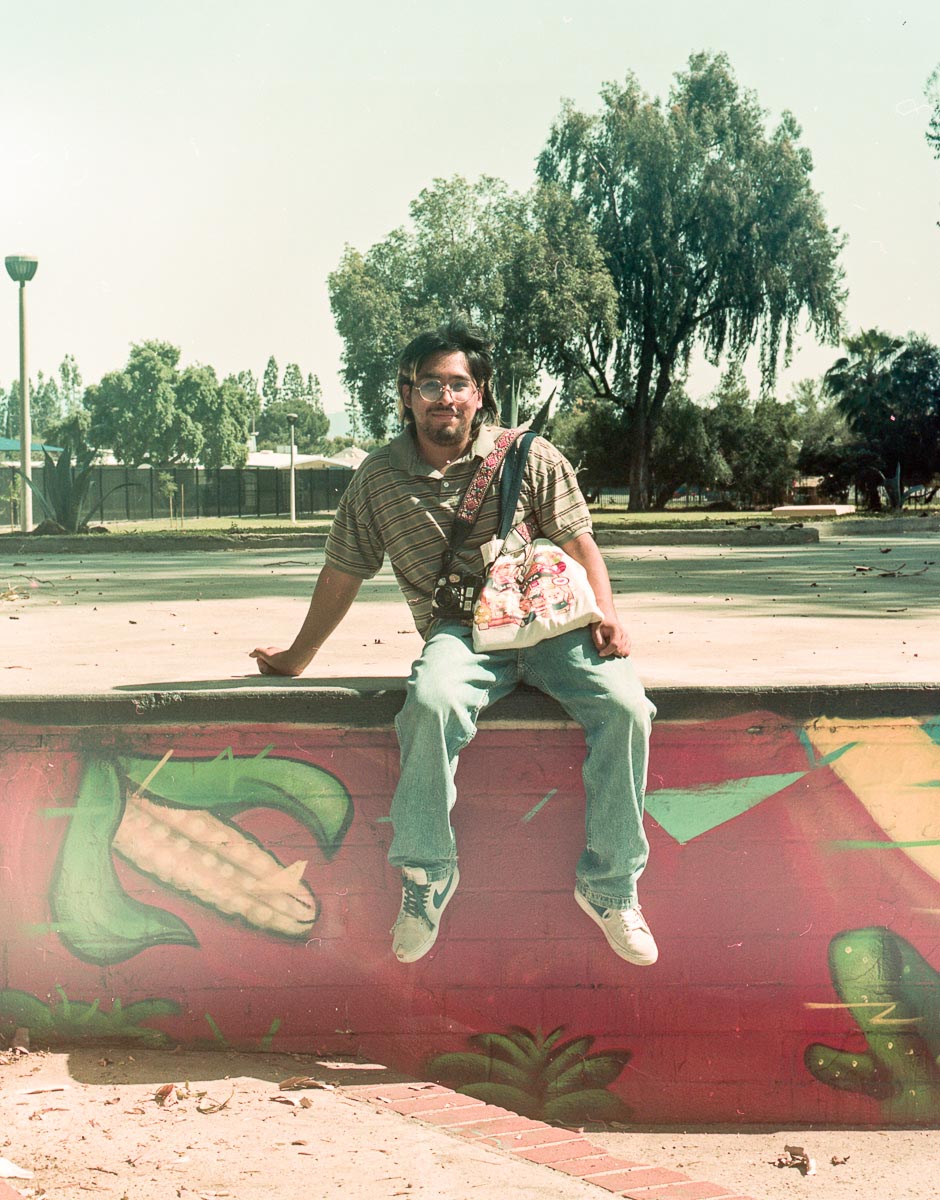

Kira Dominguez Hultgren

Do you work on distinct projects or do you take a broader approach to your practice?

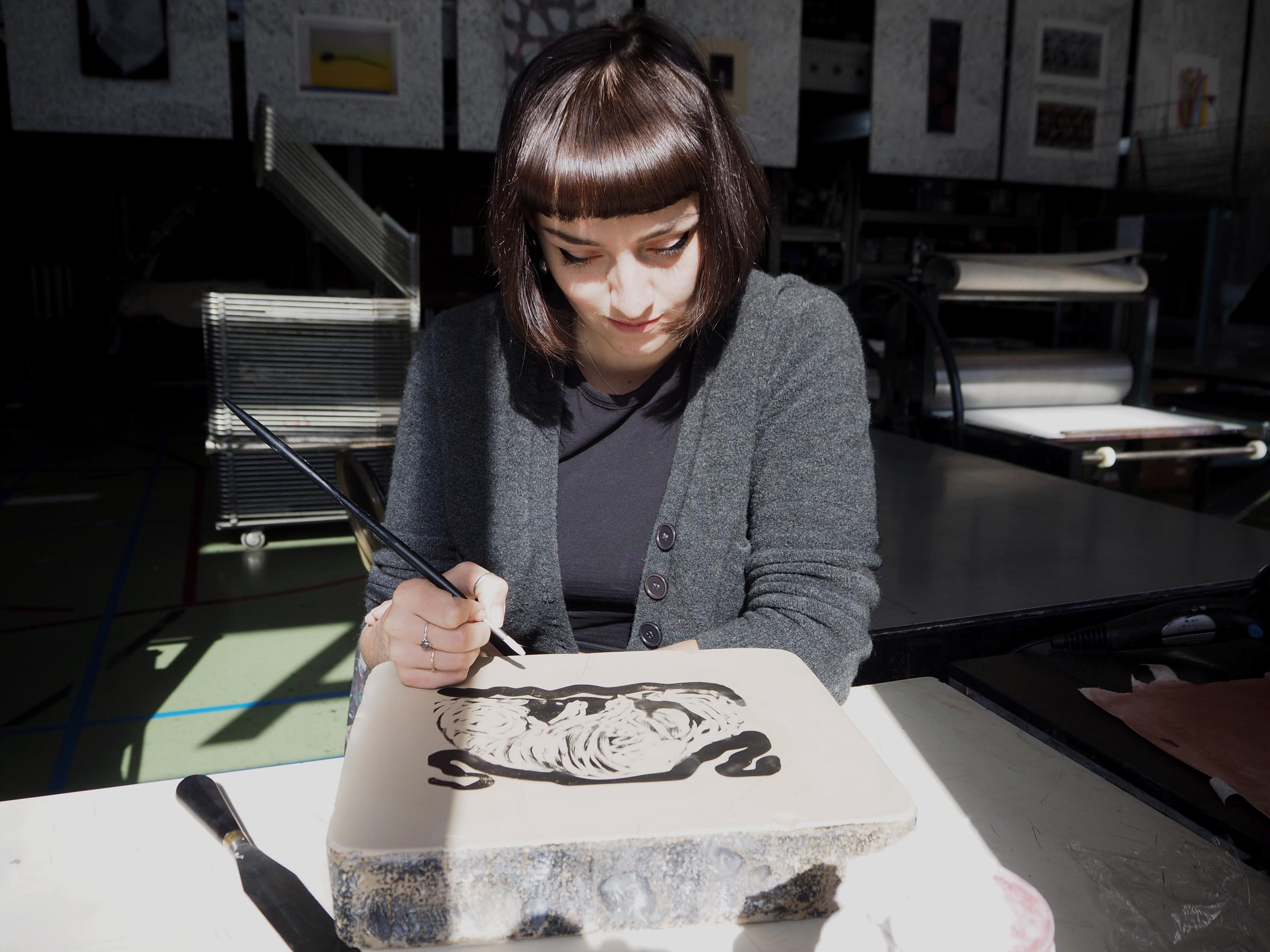

My process is very much tied to this question of working on distinct projects versus a broader approach. When I begin any project, whether writing or visual, I begin with the material and see where it takes me. Often I have an idea, an interest, a spark that draws me to material, but it is really hard for me to “see” the project, to outline it, before I have begun. So I start with yarn or quotes or images spread across the studio floor and then I quite literally begin to step through them, to recombine, to drag across, to feel my way through it. Similarly, I would define my practice as a whole then of diving deep into distinct projects, whether it’s a commission or for a show. Once I have the projects completed I can spread each out on the studio floor (or the documentation across my screen) to see how themes emerge, circle back, are at odds, or intersect.

What’s a typical day like in your studio?

Every day is different! My favorite days are sometimes like today, when I am given the opportunity to reflect on what I do and why, and then go on a bike ride afterwards! Other favorite days are spending fourteen-hours straight in the studio weaving. I try to find the balance between research/making, research/writing, research/material-scavenging, research/application-writing, research/social-media posting and research/teaching. At the end of the day, everything is research (from the Old French cerchier, to search), an opportunity to look again, to look closely, to sort through, to figure out, to question, to follow, to question again.

Who are your favorite artists?

It’s an evolving list! But those at the core of it are: Mary Coronado (Mapuche/Argentina), Verónica Vides (El Salvador), Consuelo Jimenez Underwood (U.S.), Melissa Cody (Navajo), Olga de Amaral (Columbia), Nadia Myre (Algonquin/Anishinabeg/Canada), Faith Ringgold (U.S.), Juanita (Asdzáá Tl’ógí, Navajo, 1845-1910), Luz Jiménez (Mexico, 1897-1965), and Dalip Kaur Bains (India, 1910-1992).

Where do you go to discover new artists?

Since I am drawn to those artists whose stories I want to retell, I am often finding new-to-me artists through searching through museum and library digital archives. I frequently end up tracing an exhibition catalogue to the non-circulating, rare books collection of a library, or end up in contact with anthropological or textile archivists to source images. I enjoy the search!

Kira Dominguez Hultgren is an artist based in Chicago who recently received The Hopper Prize. To learn more about the artist: