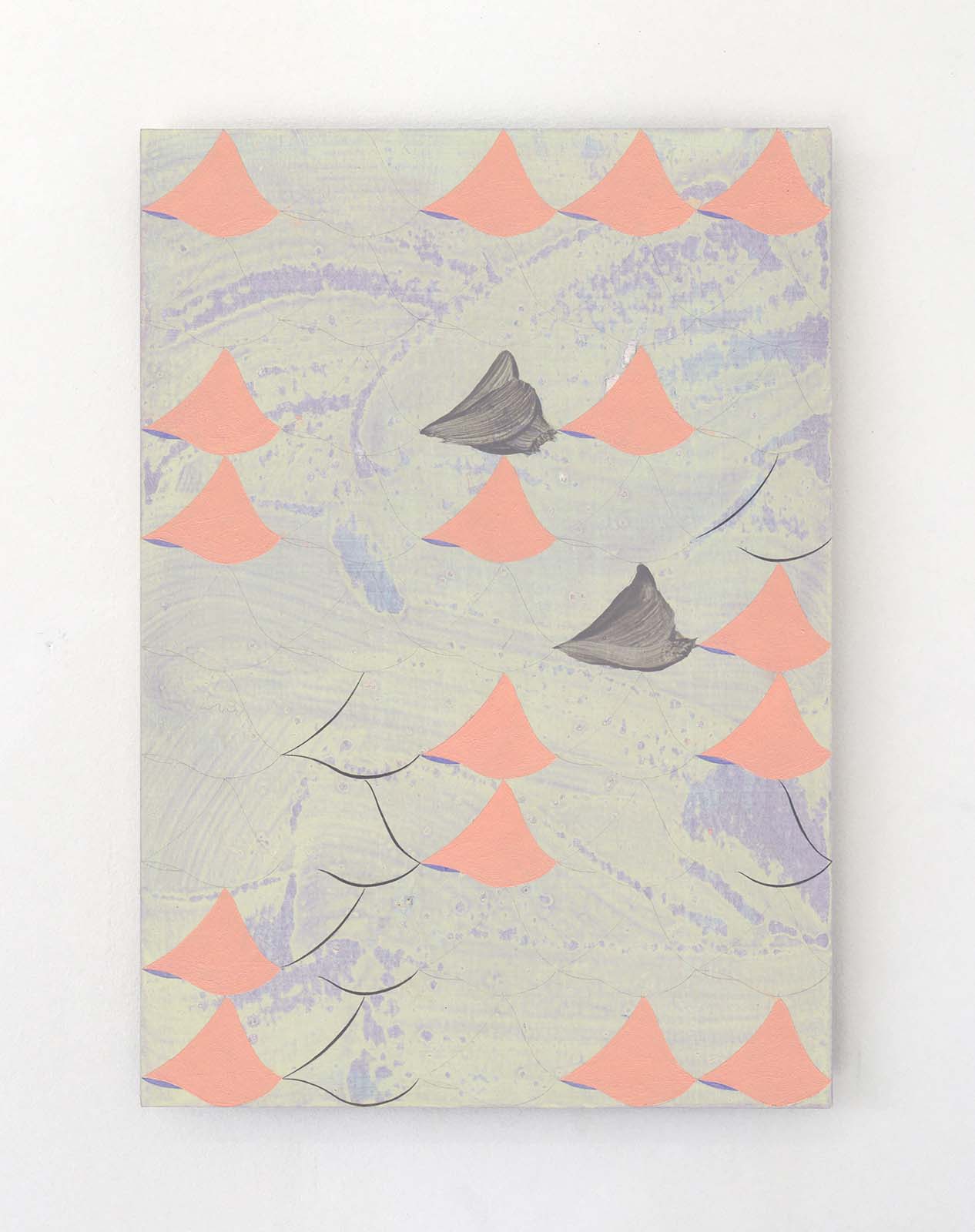

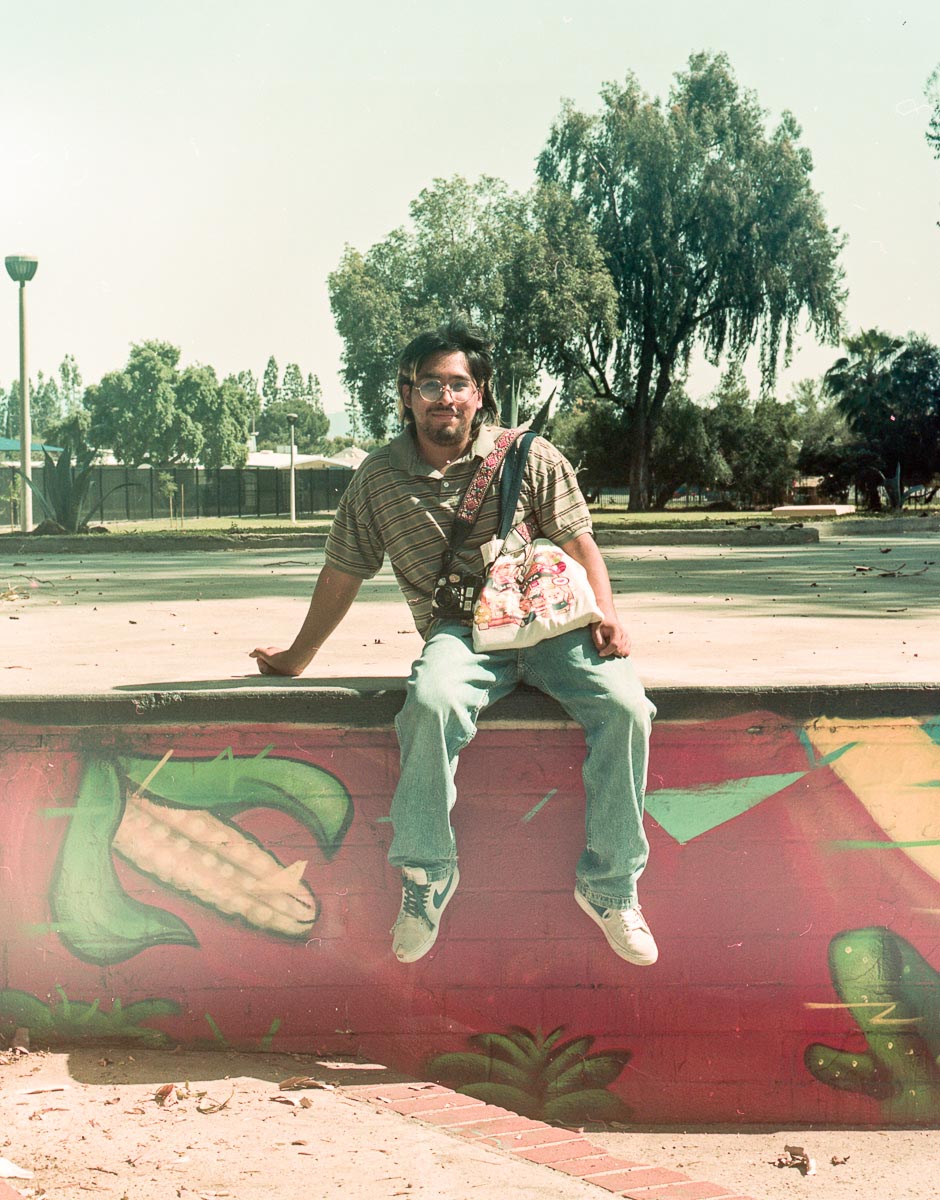

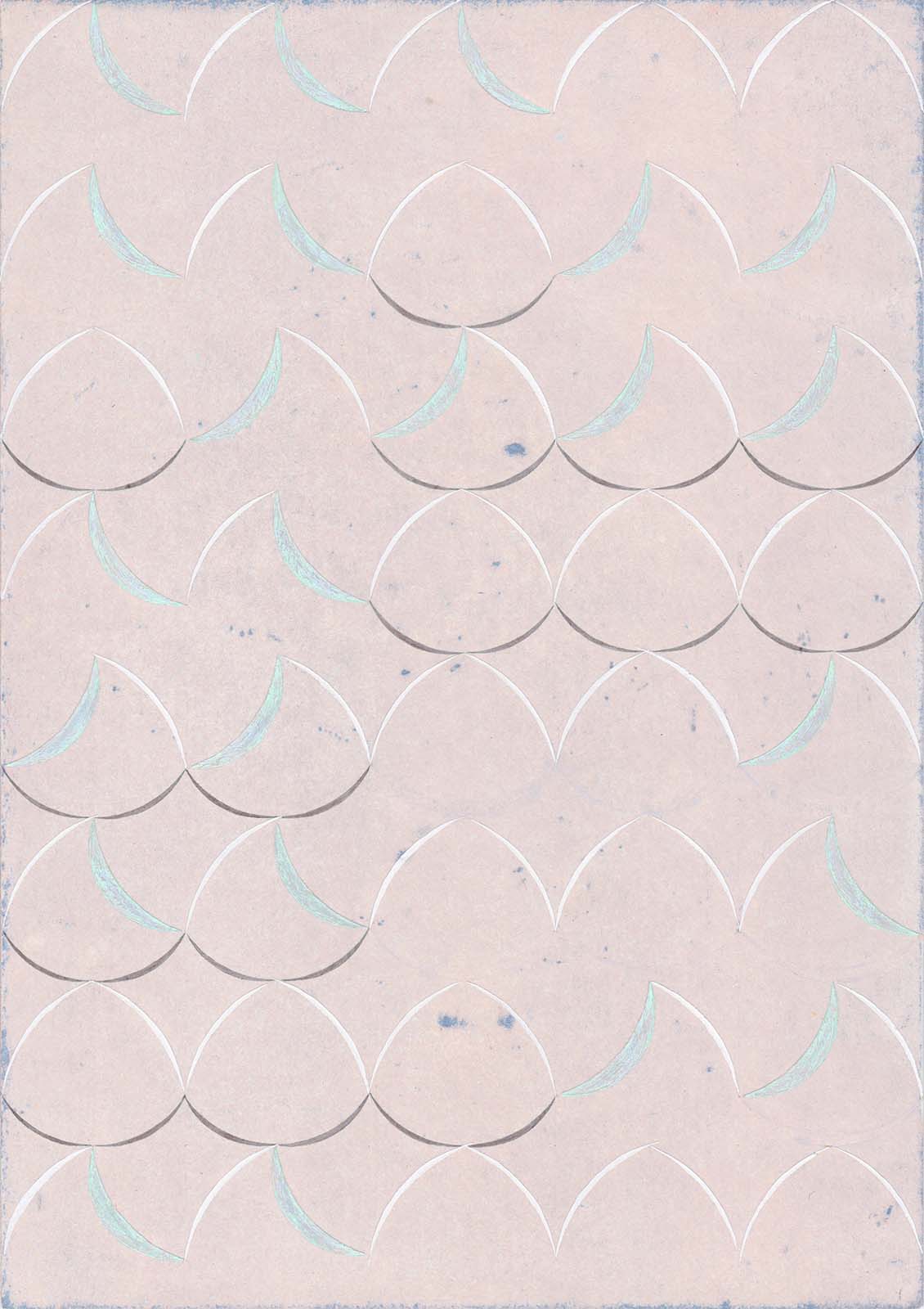

Jinyong Park, i- i-, acrylic on paper, 29.7 x 21 cm, 2018

What’s your background? How did you get into making art?

I was born in Seoul, Korea, and grew up there until I came to London, England, when I was twenty-three years old. That was six years ago. As a child, there were many things that I wanted to be when I grew up, but I found the most meaning in being an artist. I studied Fine Arts at Kookmin University in Seoul for my BA, where I became interested in language and its relationship to painting. My research focused on my identity as a speaking subject that oscillates between unconsciousness and social constraints, and my painting explored this relationship. Since I moved from Seoul to London for my MA in painting at the Royal College of Art, my bilingual experience has enabled me to think about Korean and English more distinctively. Thereby, I have incorporated my daily linguistic experience into my work and created an abstract language that imaginarily exists between my mother tongue and foreign languages. My practice is my way of responding and adjusting to the UK’s fundamentally different and diverse language system.

What are you currently working on?

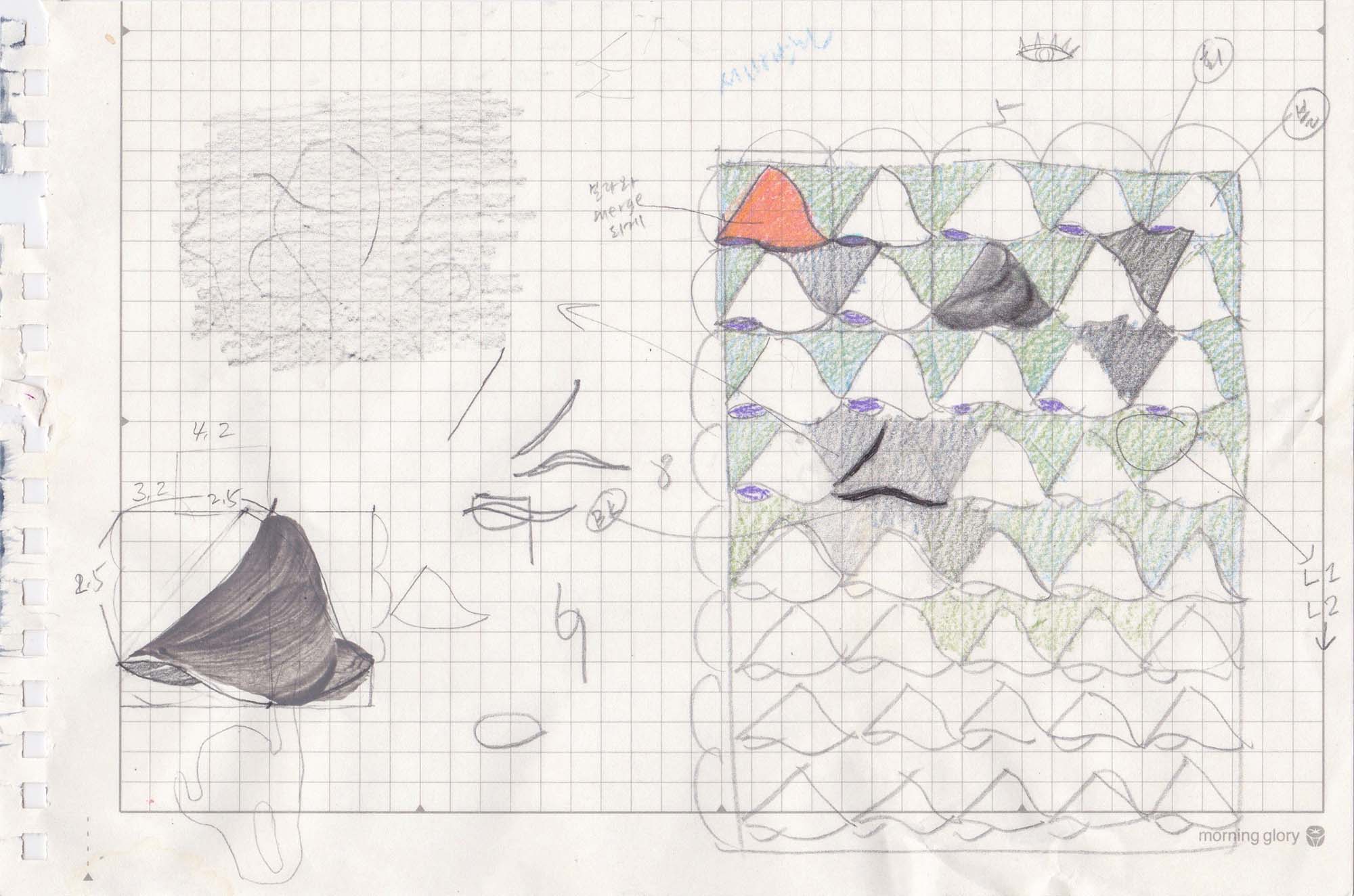

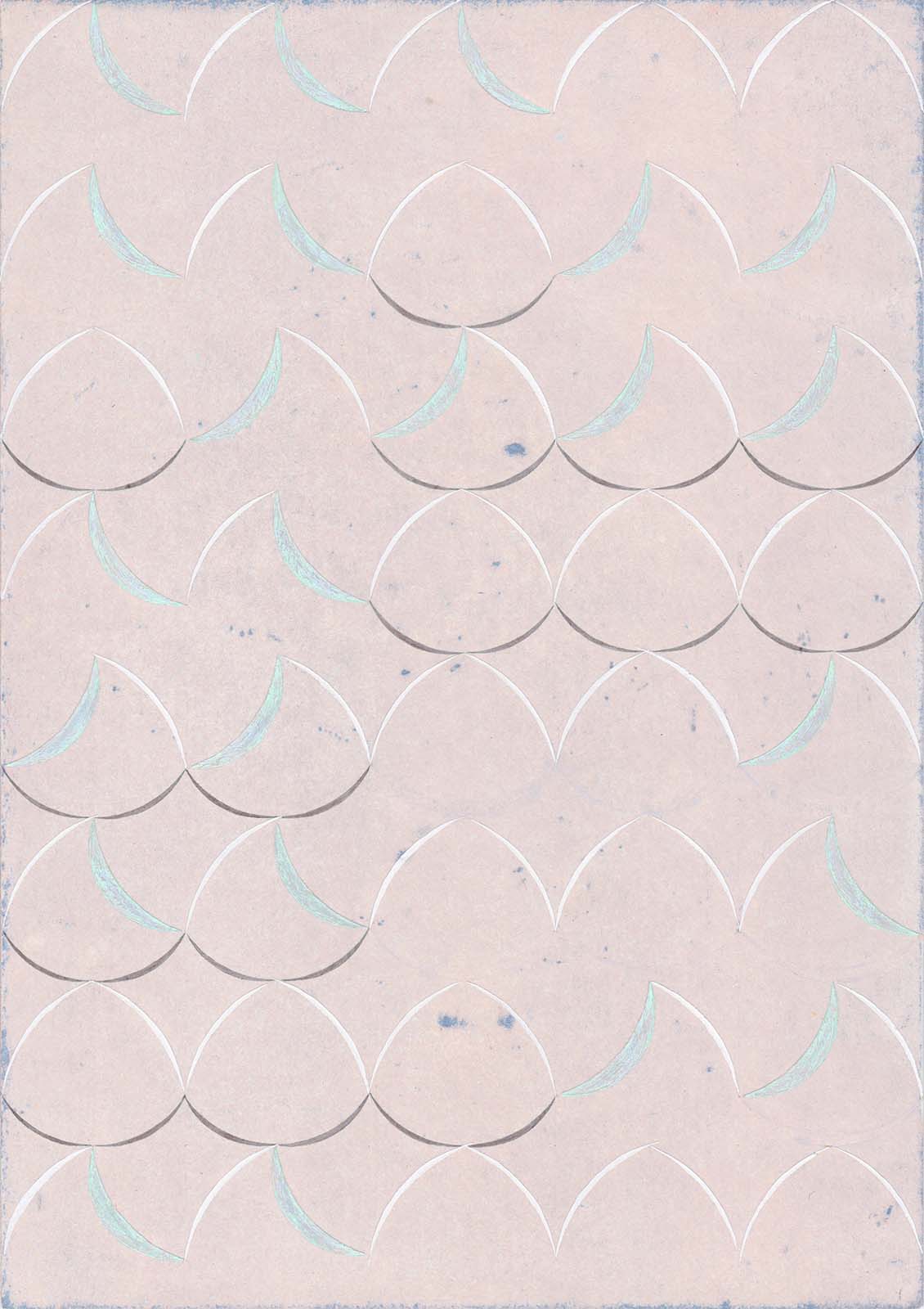

Recently, I made a series of A4-sized paintings that constitute my own geometric hieroglyphs; this body of work is based on my linguistic experience. When I experience spoken words–whether I understand the words as meaningful or only as sounds–I recognise this as both a physical and a psychological experience. I choose one of the words–more likely I happen to be occupied with that word–and then I think about my personal relationship with that word. It is based on my knowledge, associative memory and imagination about the word. This includes bridging the gaps between my mother tongue and foreign languages in a random and illogical way–one sound can have different meanings in different languages, for example–which composes an internal wordplay. This process of thinking is intertwined with my bodily responses to the spoken word’s phonetic qualities, such as length, tone, stress and intonation. I translate the abstract perception and my body’s sensory experience into my imaginative hieroglyphs. Each of them embraces and delivers the personal narratives of the studied word. I think of my painting as a manuscript, rather than as a representative image on paper; it is my way of working as a writer who develops the palimpsest in one’s own language. I paint a medium on the paper and sand it several times so that the paper is no longer ordinary. I also work with drafting tools, such as sharp pencils, rulers and bradawls. I repeat the process of painting, sanding, and drawing, which engenders unexpected and random changes of the image, as well as collects traces and flaws on the surface.

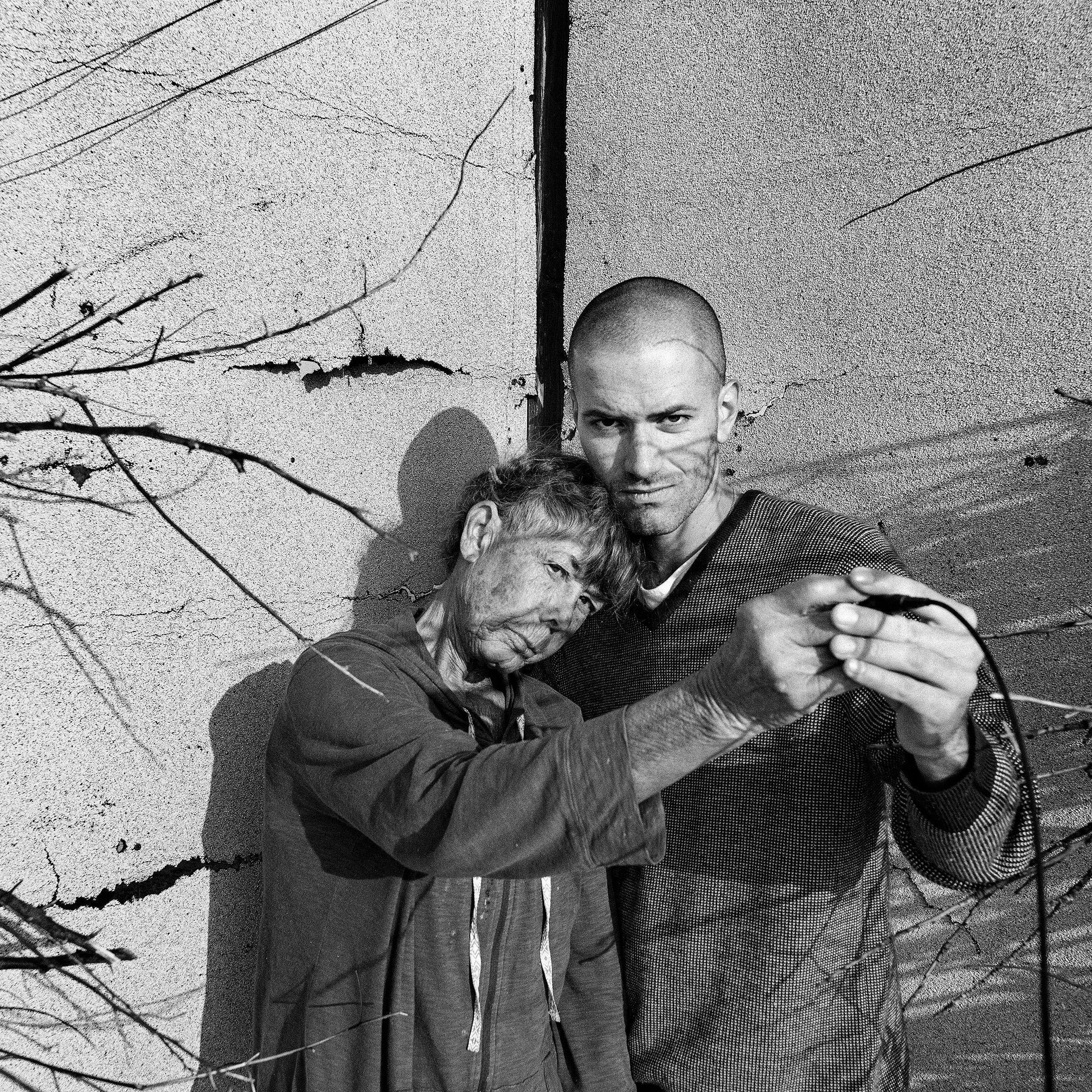

Jinyong Park, laim, acrylic on paper, 29.7 x 21 cm, 2019

Do you work in distinct projects or do you take a broader approach to your practice?

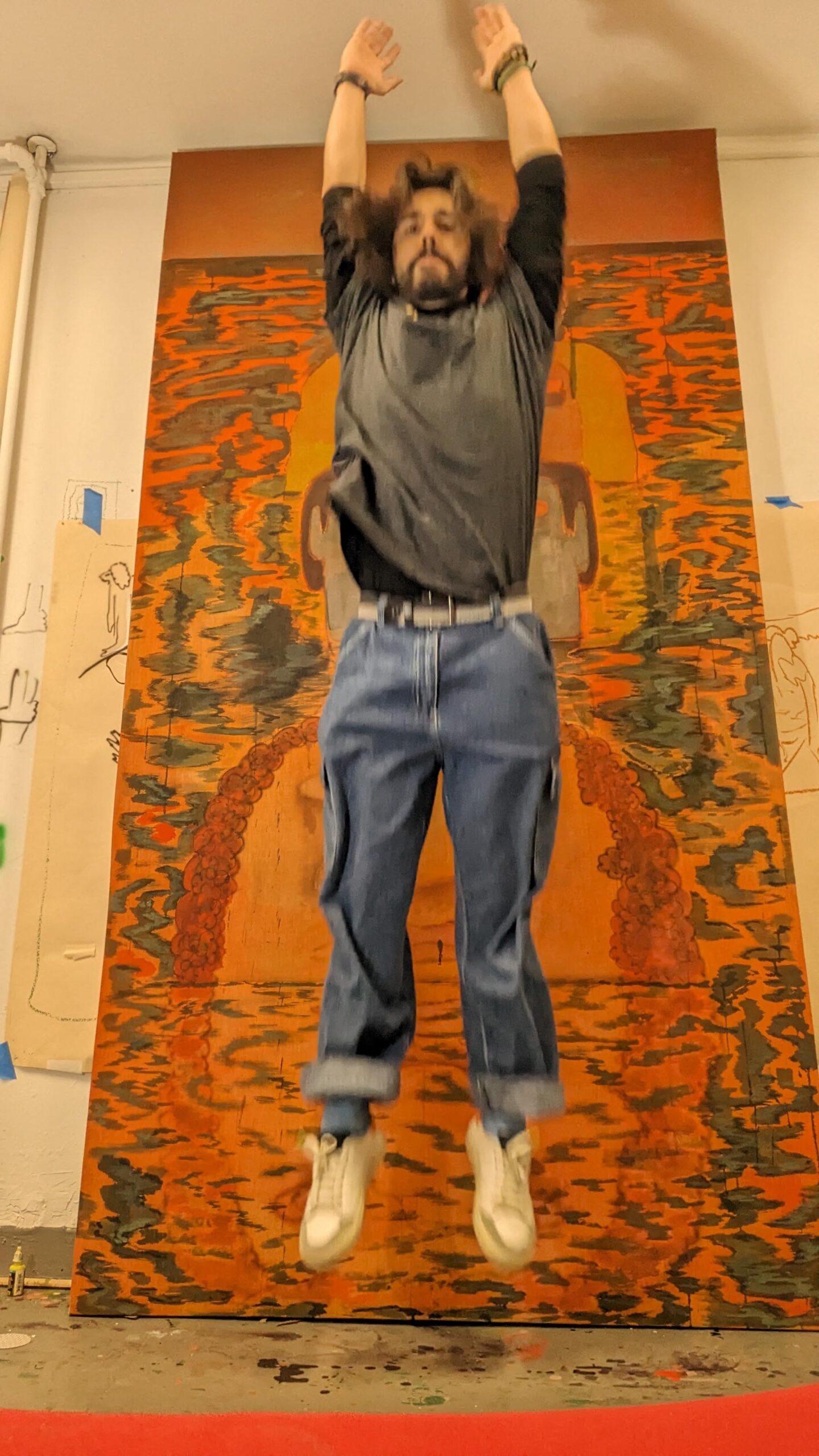

My practice is project-based because of its consistent form. I tend to examine an idea methodically, and then I use the idea repeatedly if it is good. I recently went back to large canvas paintings based on my pieces that used paper, and it took me more than six years to find a comfortable way to navigate this return. The six years were, of course, not only about this question, but the persistent question about canvas has somehow reinforced my ideas about working on paper. Now, I am working on 155 by 155-cm paintings on canvas, which will constitute another body of work along with the A4-sized pieces on paper. The size of the canvas reflects my personal height and the full span of my arms, which acts to include my own physicality in the paintings. I have set up this parameter to explore the meanings of these new works and their relationship with the series of small paintings.

I translate the abstract perception and my body’s sensory experience into my imaginative hieroglyphs.

Jinyong Park

What is a typical day like in your studio? What is your schedule like, how do you divide your time?

I try to schedule my day job on or around the weekends so that I can go to my studio on weekdays like ordinary office workers. Luckily, my studio is located near my home in South East London. I appreciate that I don’t spend my time, energy, and money on commuting, but there is one minor drawback: my day continues even after I leave the studio. I work in the studio from morning until evening, which usually goes by quickly. While working on a small painting on paper, I am sitting down all day in front of my working table. Then I have a dinner break at home and continue working, such as working on applications and emails–and sometimes, interviews like this one.

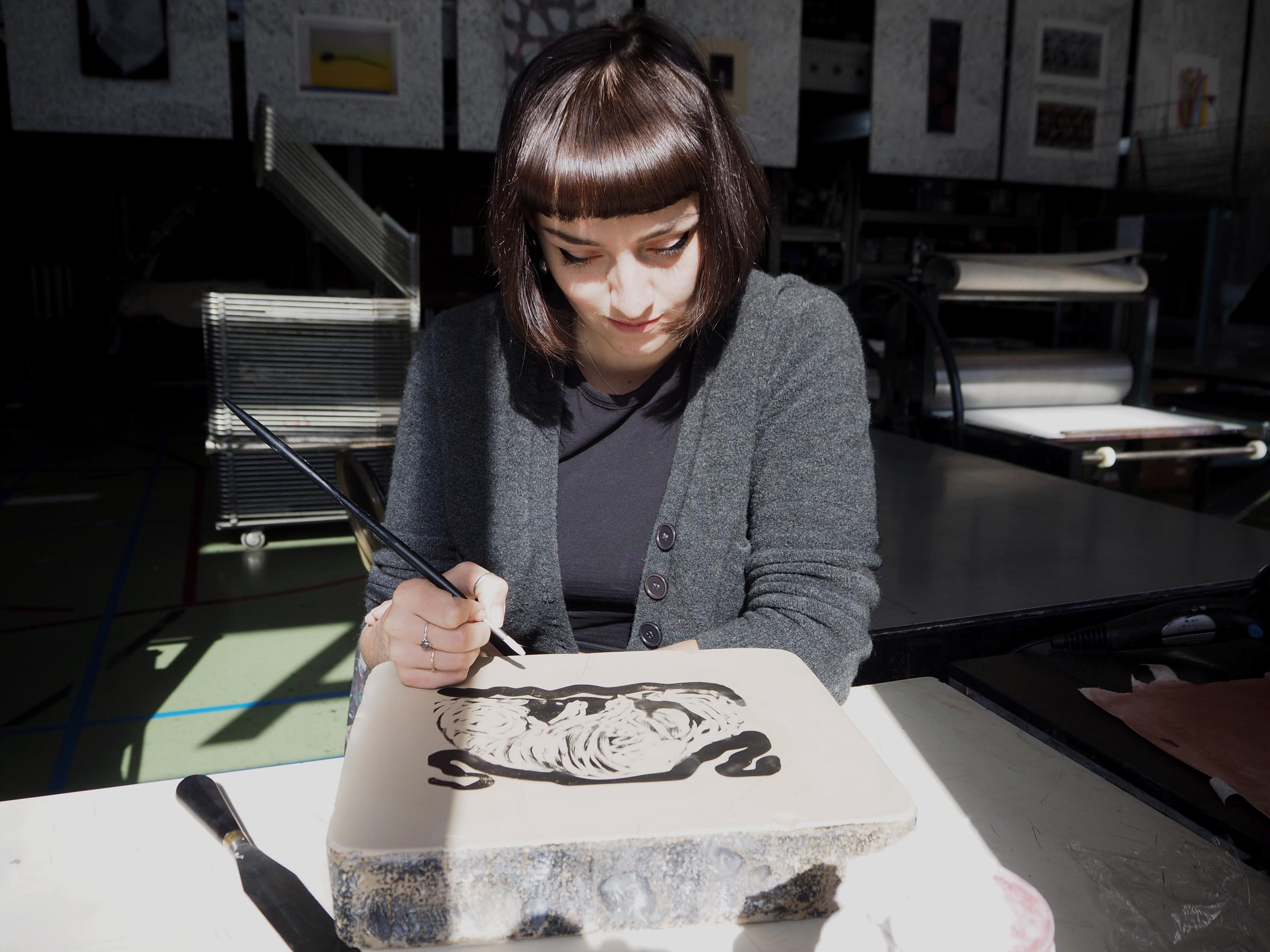

Jinyong Park in her studio, 2019

Jinyong Park's studio, 2019

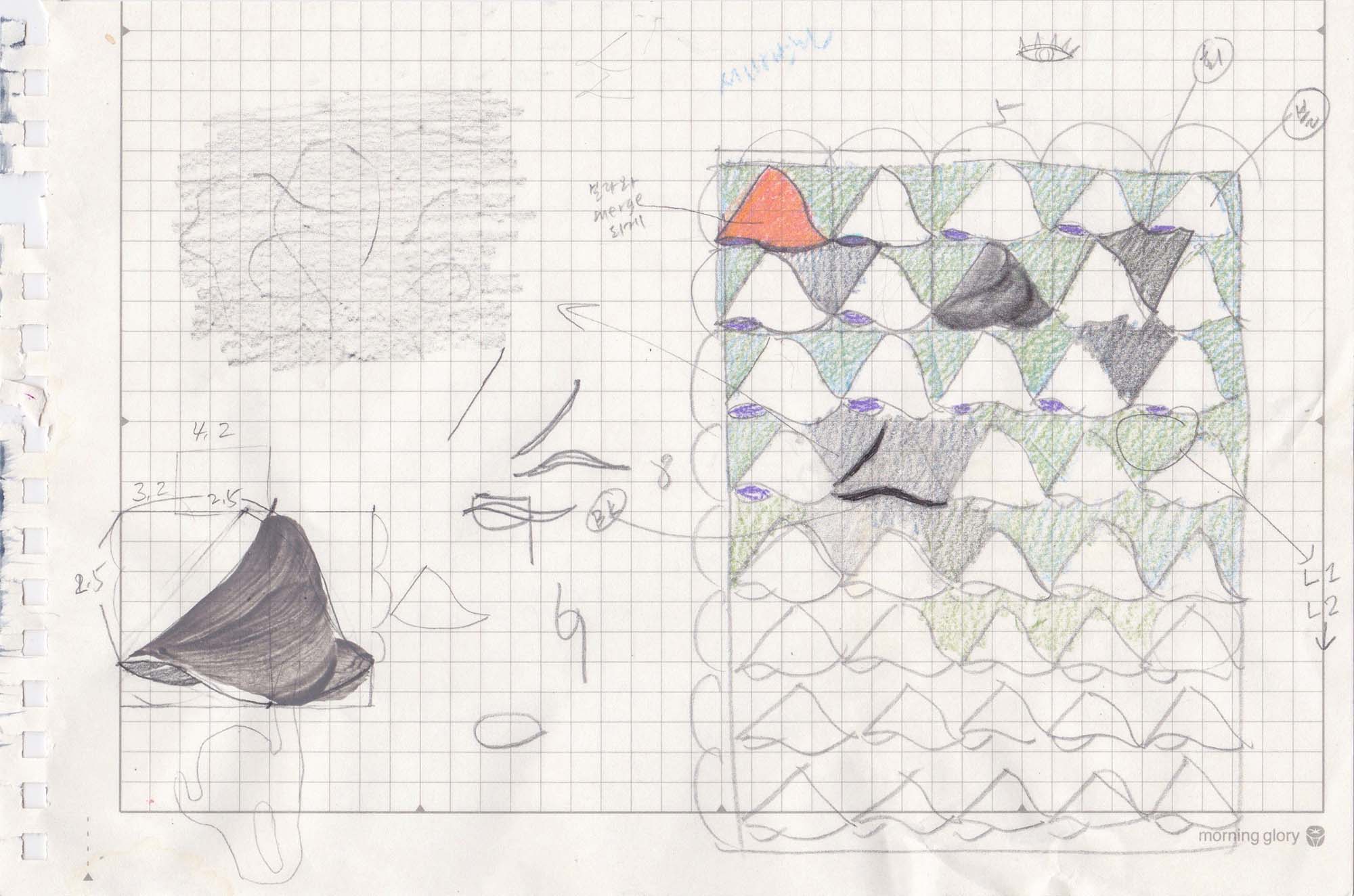

Jinyong Park, Drawing for 'laim', 2019

Given our current cultural climate, the importance of artists is undeniable, we need them now more than ever. Do you find the social responsibility intimidating at all or does this help fuel your work?

Considering that cultural issues are related to other social issues, I believe that everyone, not only artists, does what they can do on their part; there is no need to be intimidated. Artists’ social responsibilities lie in identifying a problem and then addressing it in their work–and thereby, representing contemporary questions. My work is inspired by my daily experience as a migrant, and it touches on the matter of language identity, which is underrepresented. Though it is not explicitly political and confrontational in comparison to other issues, such as race and gender, it is an issue that I face daily–and my work is one of the ways I respond to it.

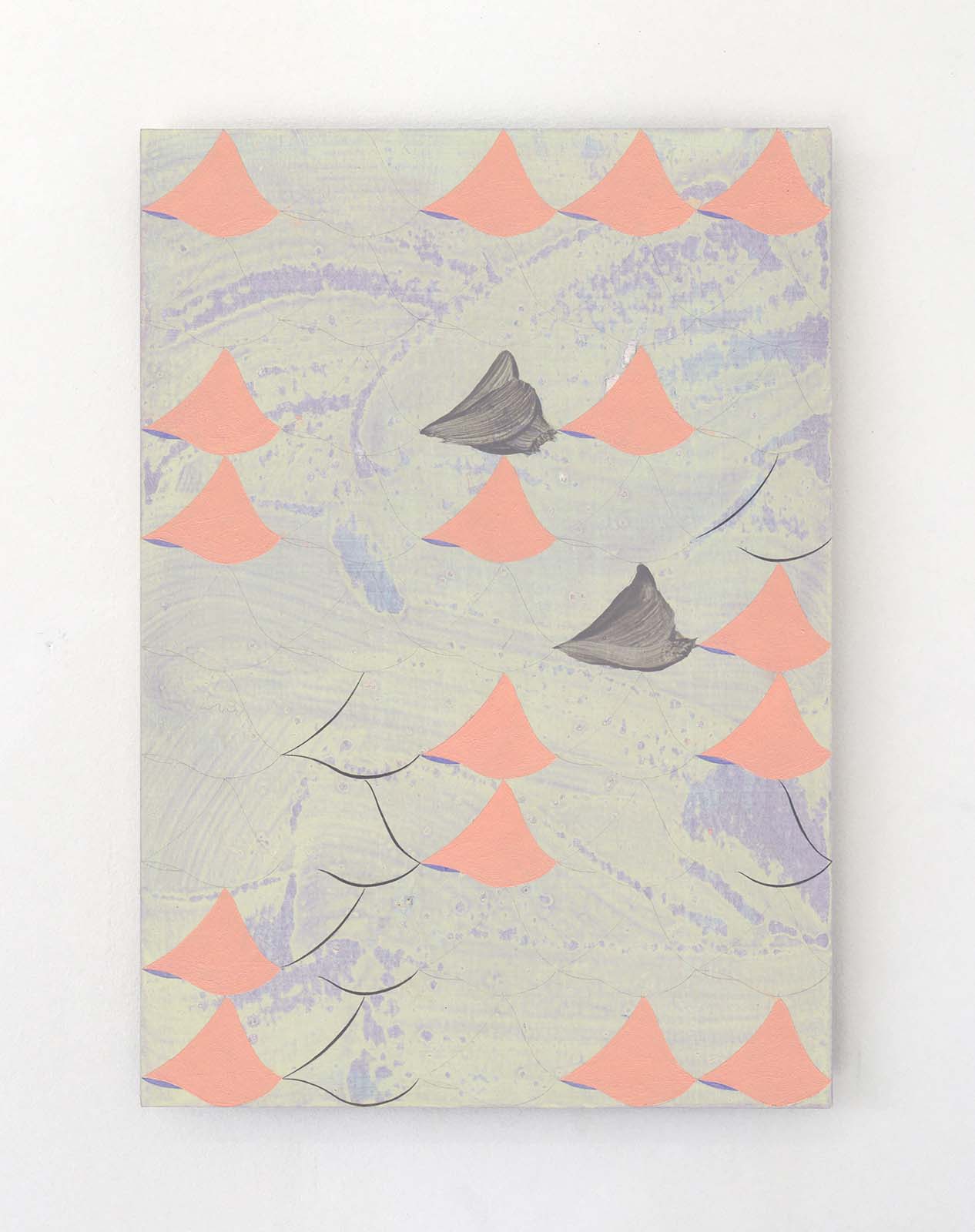

Jinyong Park, darl, acrylic on paper, 29.7 x 21 cm, 2018

What methods do you find most productive in promoting your work?

I thought about this question for a while and compared in-person opportunities with social media, but I realised that it is more about balance than a black-or-white choice because each is so different.

For example, Instagram’s horizontal accessibility is undoubtedly powerful. Anyone can see my work online without restriction. Sometimes it seems to surpass the quality of an in-person experience because of its quantitative capacity. I believe that it also helped resolve initial doubts about online exhibitions that are now common.

On the other hand, in-person opportunities, such as exhibitions and conversations, enable me to share my ideas in depth, with specific people–one-to-one conversations always hit on something significant–and I have met many supportive people this way who are artists, curators, and writers. Exhibitions are still a solid method to present paintings–I am thrilled when someone steps closer to my painting to see its details. They also contextualise my work among other artists, which is a good promotion in and of itself.

What advice would you give to your younger self? How about to other artists? Are there lessons you have learned through your commitment to your practice which you think might be of value to others?

I am the kind of person who does not listen to others when I’m into something, so my younger self wouldn’t like any advice, and I don’t dare to advise others.

Jinyong Park is an artist based in London, England. She is a Spring 2019 recipient of The Hopper Prize. To learn more about the artist: