How did you get into making art?

My mom taught elementary art throughout my childhood, so art materials were always around. I have incredibly supportive parents. My mom’s parents were immigrants from Norway, so when she decided to study art education in college she dealt with the disapproval of an artistic career path that I in turn didn’t have to face from my own parents years later.

As a kid, I became interested in learning Norwegian, which led me to study at a folk high school (or better translated as “people’s college”) in Lillehammer, Norway for a year after I graduated high school.

Folk high schools are a popular gap year option in the Scandinavian countries, but they are also open to anyone over the age of 18. I studied at a small school of 60 some students with 14 nationalities represented. I was the youngest at 18, but the oldest student was in her mid-70s. It really exposed me to a cross-section of generations and cultures from many different backgrounds. This kind of school system is unique in that there are no grades or exams, so it heavily prioritizes learning through doing and student-directed inquiry. I credit that year with teaching me the motivation and drive required of a lifelong studio practice. We had studio access 24 hours a day and I used the time to experiment with techniques and materials while gaining fluency in Norwegian.

The process of language acquisition, both how a child learns their native language and how one learns languages after that golden opportunity of childhood has passed, is really fascinating to me and informs my work a great deal.

What are you currently working on?

The larger project I’m working on now is a body of work of machine-stitched paper quilts that take on sculptural forms. The process involves overlapping painted strips of kozo paper to construct a sturdy yet flexible structure that can hang, drape, sag, and swoop. They are very bodily and heavily textured with vibrant, candy colors and patterns. Play is becoming increasingly important as both method and subject in my studio practice. Play is incredibly powerful, and serves a valuable function. It’s where behaviors are practiced, learned, rehearsed, and refined. There’s a lot of evidence showing that skills developed through play require far fewer repetitions than other methods of learning. I’m interested in what happens in our bodies and brains when we play, how play can teach us things, as well as help us unlearn unhelpful internalized messages. I’m interested in play in opposition to shame – is it possible to unlearn shame through play?

Play is becoming increasingly important as both method and subject in my studio practice.

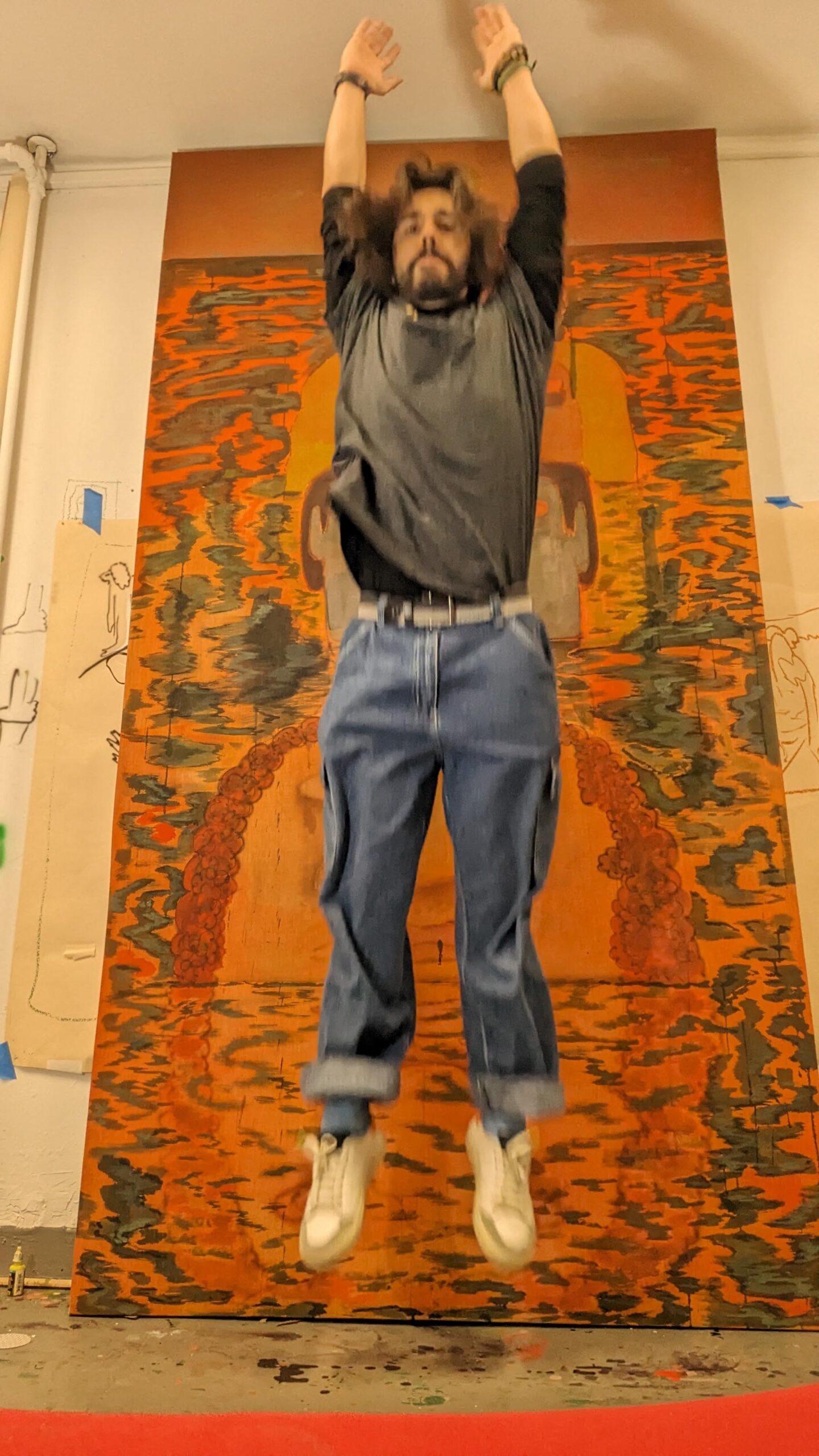

Astri Snodgrass

What inspired you to get started on this body of work?

I’m interested in different kinds of intelligence and skills that are undervalued and deprioritized by society at large. I’m particularly drawn to what the craft scholar Glenn Adamson dubs “material intelligence,” or being attuned to materials and their unique properties. He talks about how this kind of intelligence is passed down through generations and can represent centuries of skilled hands developing techniques through embodied knowledge. Rehearsal, repetition, training, play, and the building of muscle memory are what I’m particularly interested in right now.

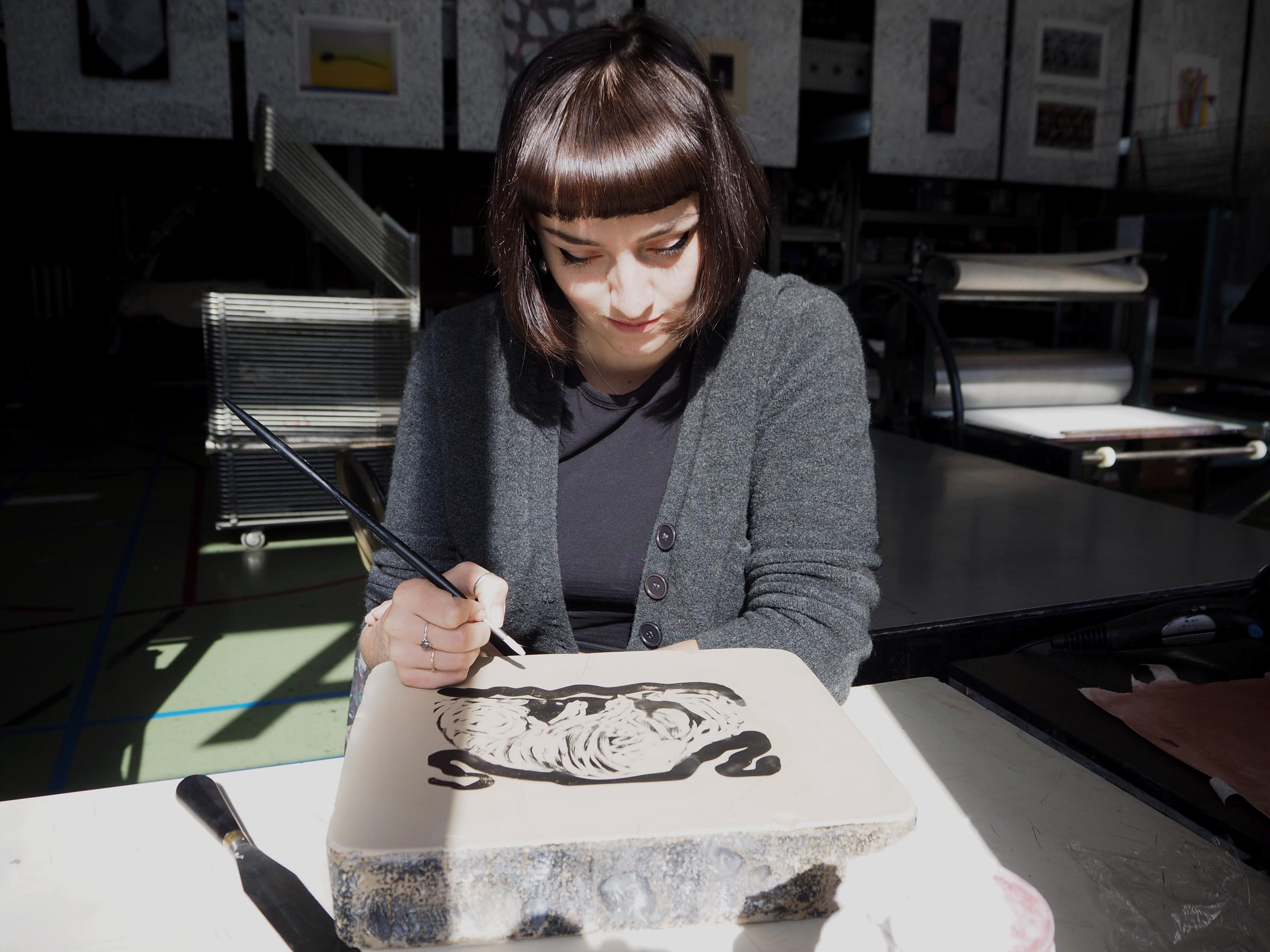

I had been thinking for a while about moving into a more sculptural visual language, and I knew I wanted my pieces to communicate through body language. This got me thinking about calligraphy, a great example of building muscle memory. A hand that has mastered calligraphy is a highly trained one. This is also informed by my childhood, as my mom is a calligrapher. I consider the paper quilts as tapering, flowing decorative flourishes at the scale of my own body. They are my own kind of “gesture drawings”, in the sense that they are drawings in space that embody their own calligraphic dance.

In order to experiment with sculptural forms at a quicker pace, I turned to crochet, a skill I learned when I was seven. Although Sculpture with a capital S felt intimidating to me, drawing with crochet felt like a homecoming. These pieces started as 3D sketches for paper quilts, to complicate the forms further, though they are taking on a life of their own. I started to correlate them to meticulously crafted medieval manuscripts and their fabulously decorated illuminated initials. Instead of literally making letterforms, I’m interested in burying words or letters in decoration, disguising them as abstract forms. I imagine the flourishes like an overgrown vine, consuming and even threatening the trellis-like structure of a word.

Do you work on distinct projects or do you take a broader approach to your practice?

I do both. I often approach my work cyclically, meaning I’ll cannibalize old pieces into new work. It’s not so much that I decide to work on separate bodies of work as I notice it happening as my ideas take on material form.

Often, a new body of work emerges from finding ways to transform a visual language from one material to another. I treat it like a translation, tailoring what’s familiar in the form to the limitations of a new material language. When you haven’t yet mastered a language, you can approach it with the poetic simplicity and creativity of a child, unencumbered by the weight of extensive knowledge. I find the tension between engaging deeply with materiality and learning the “proper” way to use a given material exciting and inspiring.

What’s a typical day like in your studio?

Before I teach in the mornings, sometimes I like to arrive early to squeeze in some creative time in the studio. I’m fortunate to have a workspace on campus where I teach. I’m actually starting to appreciate the truncated nature of studio time, finding it generative in a way. I can take the studio with me. This is what draws me to reading, writing, drawing, and crochet, because those are not studio-dependent activities but extend beyond those walls and spill into the rest of my life. Whether I’m creating something or researching, it tends to all fold into my practice and spill into the work somehow.

Last summer I had this realization that I needed to approach the sewn paper quilts with the same attention as I would bring to knitting a sweater. It requires a slow pace and a lot of patience since it’s the same repetitive action over many studio sessions and dozens of hours. This contrasts with much of the rest of my work, which comes together fairly quickly, even if the materials have been worked on for a while before I find a use for them.

Who are your favorite artists?

There are so many artists I admire and whose work I really respond to. Agnes Martin, Anni Albers, Sheila Hicks, Helen O’Leary, Sam Gilliam, Jack Whitten, and Tauba Auerbach are just a few.

Where do you go to discover new artists?

I’m always looking for new artists. I really like Two Coats of Paint, BOMB magazine, Gorky’s Granddaughter, and art podcasts like Sound and Vision. Whenever I apply to opportunities like exhibitions or residencies, I look at artists who have been invited in the past. It helps me get a sense of the kind of work that might fit the opportunity as well as giving me a broader range of exposure to what’s happening in the art world more broadly.

Learn more about the artist by visiting the following links: