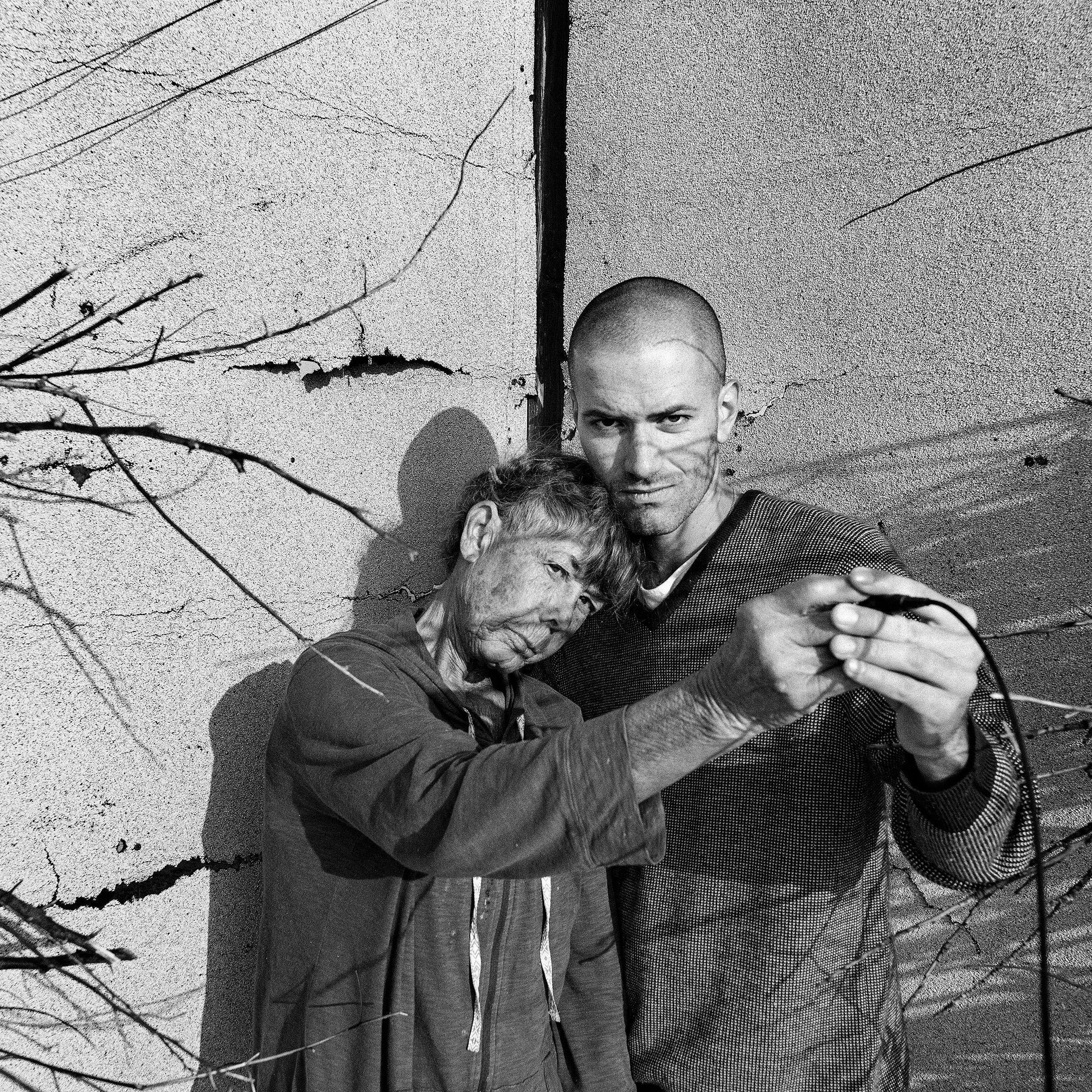

photo: Theo Schear

Maja Ruznic & Eurydice

To start, tell us about yourself. What’s your background & how did you get into making art?

I was born in Bosnia & Herzegovina in 1983—when it was still called Yugoslavia. My mother and I fled as refugees in 1992, when the civil war broke out and lived in various refugee camps throughout Europe—finally settling in the US (San Francisco, CA) in 1995. My mom always encouraged me to make art, even during the war-years. I developed a love for painting as a kid and still love how sensual it is. I prefer the word painter to artist when describing myself, because all my ‘ideas’ come through the act of painting, not thinking.

What are you currently working on? Describe your most recent body of work.

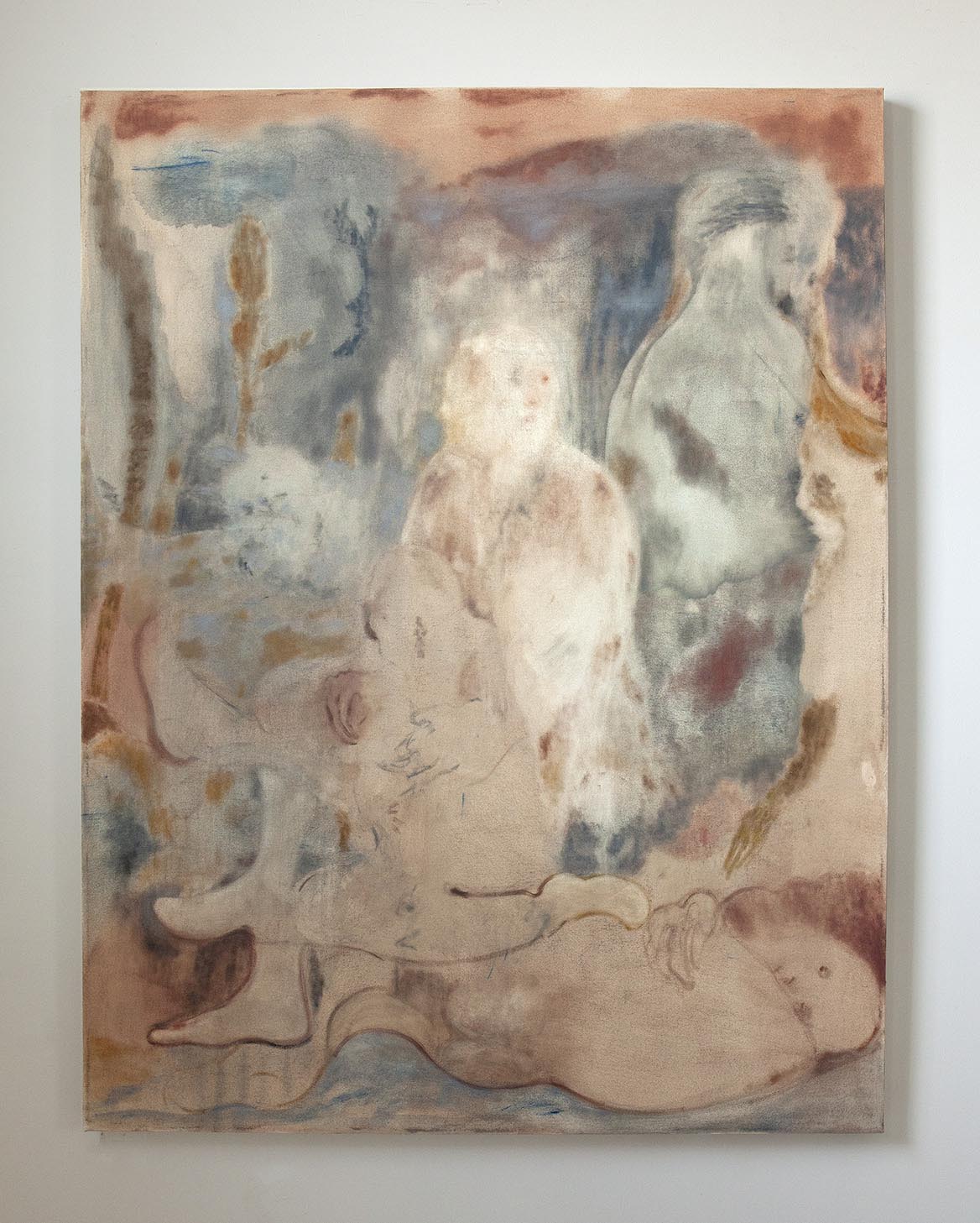

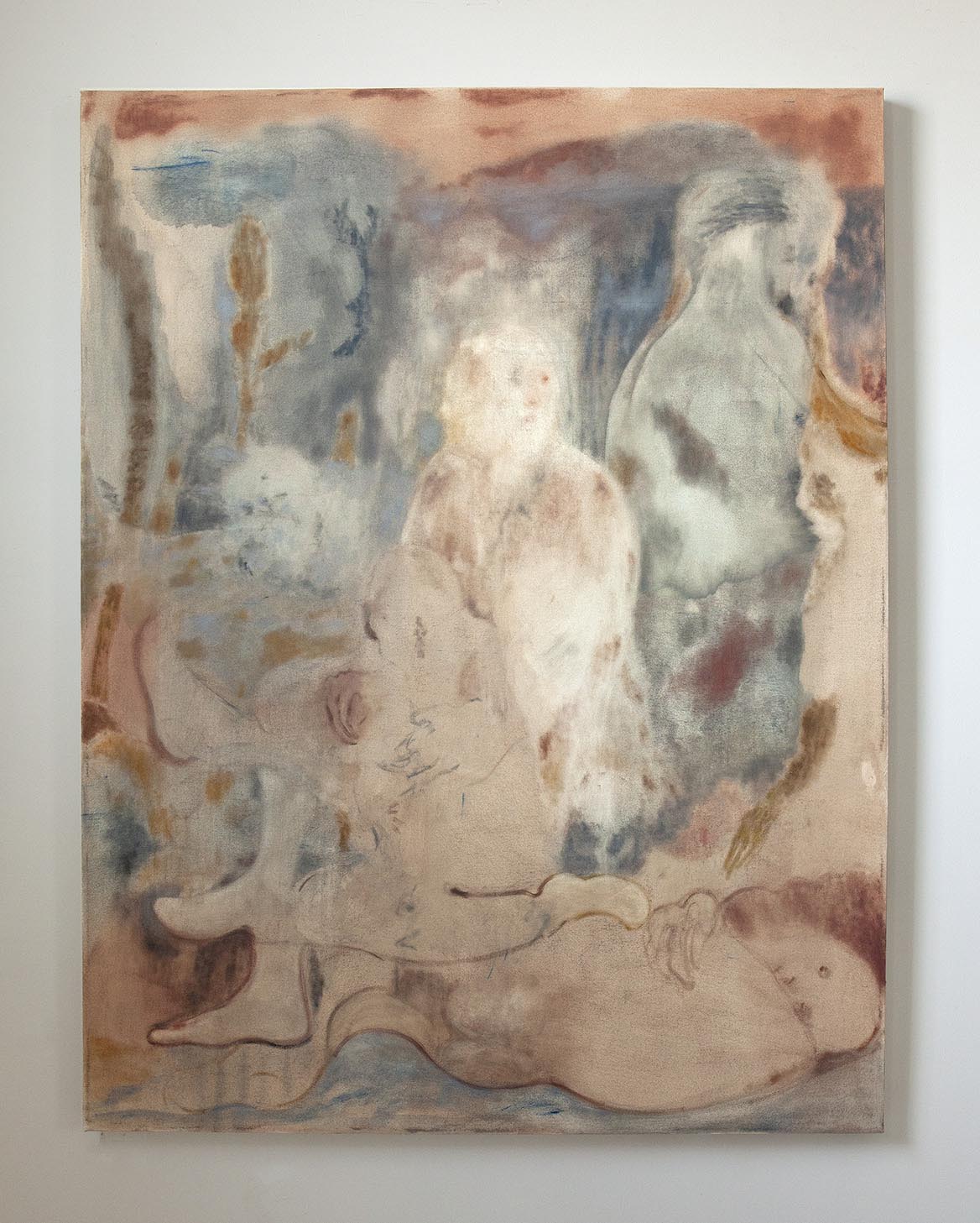

I started a new series of paintings in the beginning of the year. I have been wanting to change my palette since we moved to New Mexico, about a year ago, but found it difficult. I’m finally using colors that I’ve been craving. They are muted, weathered, perhaps even old-looking. The series is called “Sleep Seekers”, depicting amorphous beings looking for sleep. I’m using sleep as a metaphor for all things subconscious, feminine, intuitive, subliminal etc. I think of my figures as ghosts-like-nonverbal-beings. They are composed of memories—therefore unstable and slippery. The process of painting is like trying to remember a dream or even something that may or may not have happened. It is a way of touching what psychoanalyst Bracha L. Ettinger refers to as the ‘matrixial borderspace’: the space of shared affect and emergent expression, across the thresholds of identity and memory. I’m curious about the space between feeling and language and through my work, I try to give that ambiguous threshold some form. Like a thought or feeling which precedes language, time periods like dusk and dawn are moments right before a shift in light occurs. That transition often looks holy, even celestial. These transitional moments are illuminating and contain an eternal quality that I try to evoke in my paintings. The light at dawn and dusk diffuses edges and forms seem to blur together leaving them porous; appearing and disappearing at once.

The Undoer of Knots, oil on canvas, 44x33 in, 2019

Invocation, oil on canvas, 84x74 in, 2019

Where do you find inspiration when starting a new body of work?

I usually start a new body of work when I get sick of my current work. This happens about every 6 months. I get bored with myself after I’ve made enough work that looks too much alike. I’m skeptical of repetition, perhaps because it makes me think of capitalism and disease. Something about change makes me feel like my aesthetic spirit is healthy. Books inspire me—but more than anything—it is colors that bring me to new work. I’ll often start a new body of work with a color that plays the role of a burning flame: magenta, king’s blue or a dirty yellow for example. Forms grow out of colors and out of those forms, figures, plants and amorphous creatures.

Do you work in distinct projects or do you take a broader approach to your practice?

I have three stations in my studio. The main is the oil painting station, the other two are for works on paper and fabric sculptures. Having fun in the studio is very important to me, so I allow myself to move through the room if I feel uninspired with a specific piece. I learned this from working with kids—they often need to change things around in order to stay interested. I can relate to this, as I am one tall kid!

Describe a day in your studio. What is your schedule like, how do you divide your time?

I wake up early (around 6 am) and read for about an hour with my coffee. Then, I exercise for another hour—go to the gym or just run around my neighborhood. By the time I get to the studio (around 11 am), my body is alert and my mind clear. I think of physical movement as part of my painting practice, which is hard on your body. I really started noticing this when I started painting at a larger scale. I usually stay in the studio until sunset, and sometimes longer if I’m feeling possessed. I don’t like painting with too much artificial light, so night’s arrival is my sign to slow down and get home. The day-to-day in the studio varies. Sometimes it’s all painting, while other days are spent in the wood shop building stretcher bars. Some days are purely administrative, where I answer emails, create pdfs, get work ready to be shipped out, etc. I also paint in bursts, meaning I am not a slow and steady artist. I try to paint only when I feel intoxicated and full of a certain kind of energy. I’ve tried painting when I don’t feel that way and have learned that the results are not so good. On days when that exuberant energy is lacking, I build stretcher bars, stretch and prime canvases, apply for things—do the the less creative but important work.

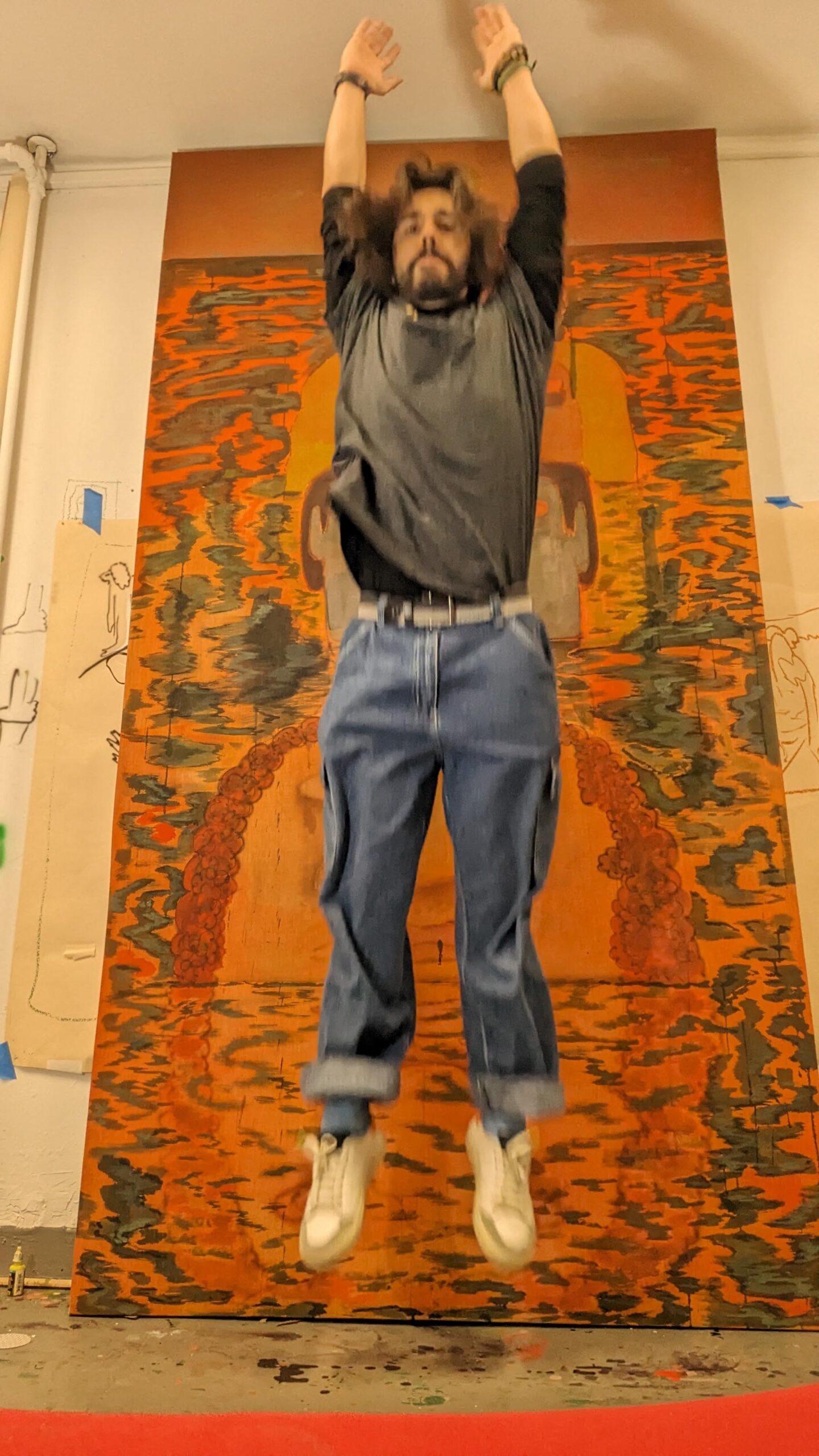

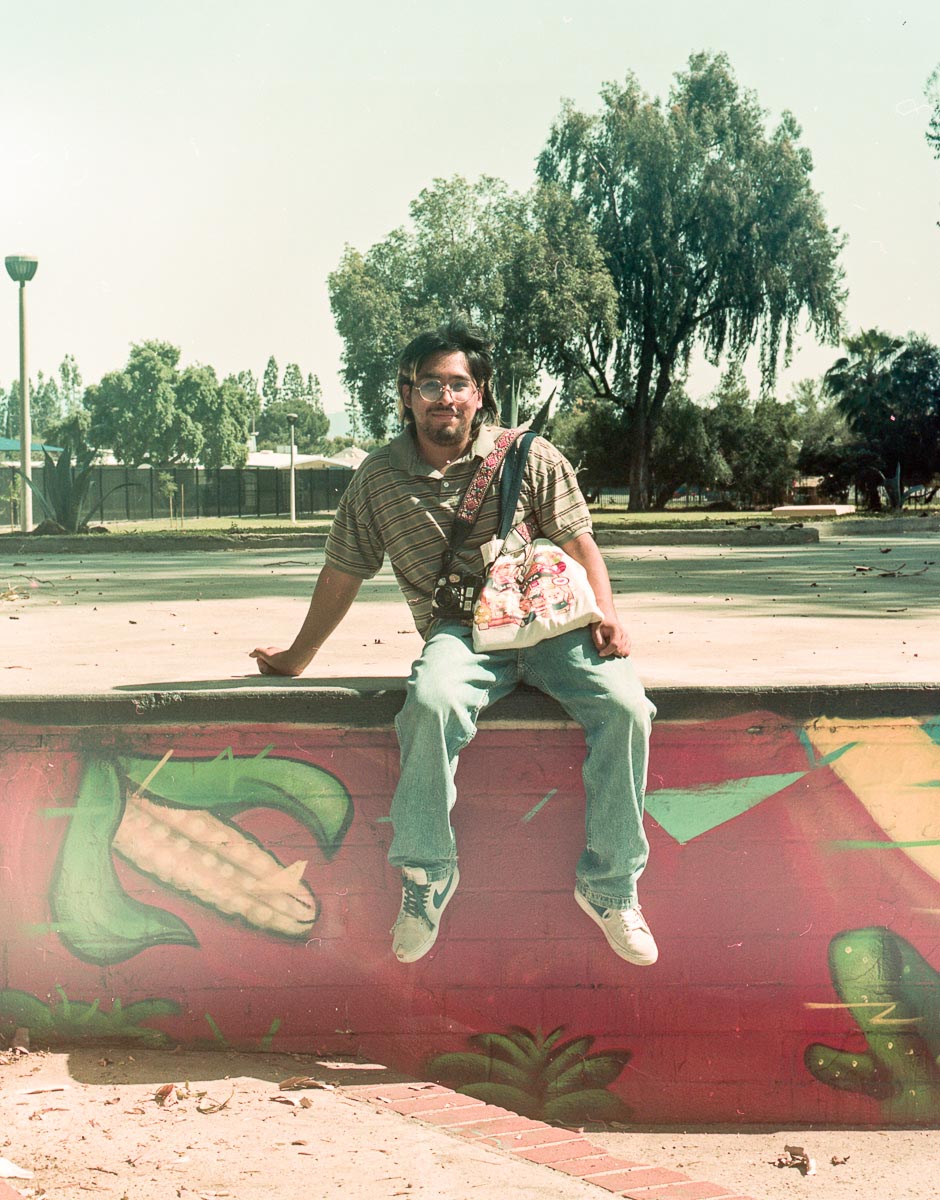

Ruznic in her studio, Photo by Theo Schear

Ruznic's Roswell Studio

Ruznic at work on The Help

Has your practice been influenced by technological changes/advances either online or through social media?

Yes in a way. I follow really fascinating people on Instagram and pay attention to what they are reading and sharing. I’ll often stumble upon a new author or artist that way. I also love how level the playing field has become because of social media. Galleries can sometimes be elitist and not care to look at your work. But now, with social media, you can create your own audience without waiting for the gallery to do that job for you. I love that part of social media.

Keep

Making Art

No Matter

What

Maja Ruznic

Given our current cultural climate, the importance of artists is undeniable, we need them now more than ever. Do you find the social responsibility intimidating at all or does this help fuel your work?

In way, what we have in the US seems freakishly similar to pre-war Yugoslavia, a place where I was born and was forced to leave as a child, due to war. It was a place where neighbors killed each other due to political and ethno-religious differences. The political divide between the right and left in the US is becoming so strong, that I worry about the same thing happening here. Everything is so inflamed and I find it difficult to have nuanced conversations with people—even artists and academics—where I hope complexity still exists. From every angle, people seem ready to attack and boast about their opinions. This ego mania and moral superiority is not a good vehicle for change, so I find myself looking back at the past and finding solace in reading and spending time with my cat, Judith. Through my work, I hope to reach a place of empathy in the viewer. Where there is empathy, there is love and at the risk of sounding like a total hippy—this is where I believe transformation happens. I can only hope that the viewers of my work feel a kind of softening and perhaps relate to the boundary-less figures appearing and disappearing on the surface. If I am responsible to do anything as a painter, I hope that it is only to invite the viewers of my work to feel deeply, become vulnerable and if I’m lucky, to make them cry.

Sleep Seekers, oil on canvas, 64x48 in, 2019

What are some of the challenges you have experienced in your practice?

The greatest challenge I have experienced in my practice is not having my work seen as political, but instead, as merely decorative. My work, which has romantic and humorous qualities, often becomes labeled as ‘whimsical’, ‘apolitical’ or ‘painterly’—like those are bad qualities if wanting to be taken seriously. The other challenge I’ve had, has to do with my background. My work deals with inter-generational trauma and this interest stems form my childhood experience of being a refugee. Sadly, I sometimes find that my childhood experience doesn’t appear to be of interest to the powers that be. Turns out, the art world is trendy, and my personal history is not in fashion. When I was in graduate school, I had a teacher who told me “Honey, Bosnia ain’t hot right now!” to which I had no response. I cried in my studio because at the time I could not believe that human suffering can be something that’s ‘hot’ or ‘not hot’. My teacher’s response to my work made me wonder: If I was making the same art in the 90’s, would it be ‘hot’ because the war was going on at the time? Would the timing make it ‘relevant’? Who decides what is relevant and what isn’t? Was I not allowed to speak about trauma? Most importantly, perhaps, who are the silencers in the art world?

What are some of the most rewarding aspects of art making?

The most rewarding aspect of art making is being able to connect with other human beings on a non-verbal level. Because of social media, I’ve made connections with artists from all over the world—even traded art. For me, being an artist is all about connecting, feeling and sharing.

Bat Child, oil on canvas, 19x14 in, 2019

What is one art related book and non-art related book that you recommend other artists read?

Art related: Fantastic Reality (Louise Bourgeois and a Story of Modern Art) by Mignon Nixon Non-art related: Matrixial Borderspace by Bracha L. Ettinger (although this is also sort of art-related)

Where do you go to discover new artists?

Instagram, friends, galleries, museums

What methods do you find most productive in promoting your work?

Most of my success has come from applying for things and promoting my work on instagram.

What advice would you give to your younger self? How about to other artists? Are there lessons you have learned through your commitment to your practice which you think might be of value to others?

Keep making mart no matter what. It seems to be the game of who can stand the longest as well as luck, but don’t let the lack of luck be a deterrent. At some point, they will have to pay attention.

Learn More

Maja Ruznic is a recent recipient of a Hopper Prize artist grant. To learn more about Ruznic’s background and practice: